The American Battlefield Trust has saved important sections of battlefield land at the site of this crucial 1862-3 battle. To expand your appreciation for this pivotal battle, please consider these ten facts about the Battle of Stones River.

Fact #1: The Battle of Stones River was part of a grand Union offensive.

In the final months of 1862, Abraham Lincoln and General-in-Chief Henry Halleck decided to press the Confederacy on all fronts. They hoped that the Confederates would not be able to shift reinforcements in time to meet the combined attacks of Ambrose E. Burnside in Virginia, William T. Rosecrans in Tennessee, and Ulysses S. Grant in Mississippi. While Burnside met with disaster at Fredericksburg and Grant’s efforts against Vicksburg stalled, Rosecrans bemoaned a lack of supplies and did not advance until December 26. Despite the tactical failures in the east and west, the grand strategy paid off for Rosecrans--Confederate general Braxton Bragg, commanding the forces in Tennessee, sent approximately one-sixth of his infantry to reinforce Vicksburg on December 16.

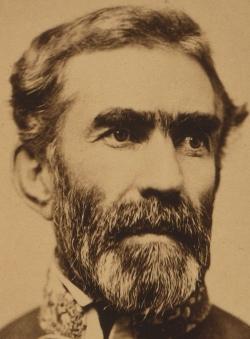

Fact #2: Gen. Braxton Bragg’s ill-considered battle plan hampered Confederate efforts during the first day’s fighting.

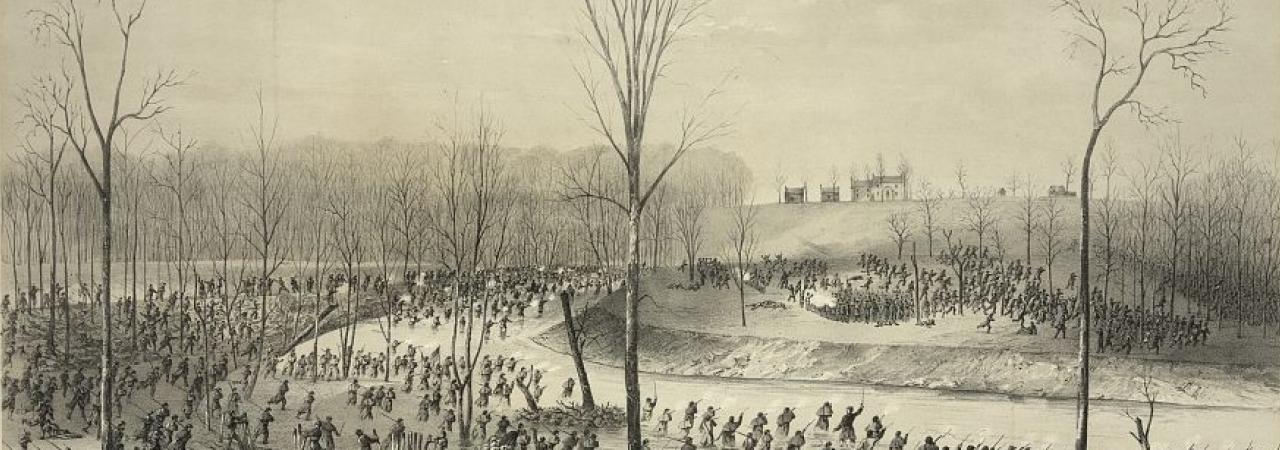

Rosecrans’s Union Army of the Cumberland and Bragg’s Confederate Army of Tennessee met on a battlefield outside of Murfreesboro on December 30. Both generals decided the take the offensive the next day. Bragg’s plan called for an attack on the Union right flank with over 10,000 men. Upon breaking through the first line, his men were instructed to wheel and drive to interdict Rosecrans’s supply line on the Nashville Turnpike. Unfortunately for the Confederates, Bragg’s orders were almost impossibly idealistic. Successful execution would require the massive attacking formation to maintain a cohesive shape as it changed direction across extremely difficult terrain—dense cedar thickets, stony outcroppings, rail fences—in the face of enemy fire. Additionally, the axis of advance would push the Union soldiers closer to their reinforcements while pulling the Confederates away from theirs. In the words of historian Grady McWhiney:

“Like a snowball, the Federals would pick up strength from the debris of battle if they retreated in good order. But the Confederates would inevitably unwind like a ball of string as they advanced.”

The Confederate assault on December 31 began before Rosecrans could put his plan in motion and thus forced the Union army to go on the defensive, but the flaws in Bragg’s plan reaped bloody consequences.

Fact #3: Maj. Gen. John McCown’s division had whiskey for breakfast before their dawn assault on December 31.

The opposing lines at Stones River spent the night of December 30 unusually close together. In some places the two armies were separated by only a few hundred yards. As part of Bragg’s attack force, John McCown did not want to reveal his position by the light of cook-fires on the morning of the 31st. Instead, he distributed a whiskey ration—most welcome in the freezing weather—and ordered his men forward at dawn. The furious assault caught some of the defenders while they were cooking their own breakfast and shattered the Union line. McCown was drawn away from the Wilkinson Turnpike as his men pursued the scattering Federals. Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne, leading the division supporting McCown’s attack, conducted the right wheel as Bragg ordered and unexpectedly found himself in the front line.

Fact #4: Brig. Phil Sheridan’s desperate defense during the late morning of December 31 averted a full-scale rout

When the Union right crumbled at around 8 A.M., Phil Sheridan suddenly found himself attacked from three sides, his 5,000 men trying to hold off over 10,000 Southern veterans. This new attack was led by Patrick Cleburne along with two fresh divisions under Maj. Gen. Benjamin Cheatham and Maj. Gen. Jones Withers. With the Confederate line overlapping his right, Sheridan conducted a fighting withdrawal through a large cedar forest with limestone outcroppings, now known as "The Slaughter Pen," to avoid being outflanked. The blue line was eventually bent into a right angle along the Nashville Turnpike, but it was not broken. Sheridan’s division was pulled out of the line at 11 A.M. and allowed to replenish their ammunition. His stubbornness had robbed the Confederate assault of vital momentum.

Fact #5: Bad blood between Braxton Bragg and Maj. Gen. John Breckinridge may have contributed to the Confederate failure in the Round Forest.

With his initial attack stalled and the Union army stubbornly keeping the field, Bragg decided to strike on the other side of the line at 10 A.M. The focal point of this new effort was a small cedar copse known as the Round Forest. The day’s fighting would give it another name—“Hell’s Half-Acre.” Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk’s corps, its men exhausted after fighting against Sheridan, launched a series of piecemeal but violent attacks that failed to dislodge the Union defenders. Bragg called on John Breckinridge’s division to renew the attack, but Breckinridge was slow in responding. The two had been at odds since an incident earlier that month, when a soldier in Breckinridge’s corps was executed for desertion. The soldier, Asa Lewis of the 6th Kentucky Infantry, had served with distinction and only went AWOL to assist his widowed mother on the family farm. He was captured and Bragg insisted on putting him before the firing squad despite Breckinridge’s vehement protests. The killing contributed to Breckinridge’s belief that Bragg did not have enough concern for the lives of his men. Only reluctantly did Breckinridge did send his units into the Round Forest at 4 P.M., where they arrived too late to make an impact.

Fact #6: A series of vague and incorrect reports disadvantaged the Confederates throughout the battle.

False information compounded the inadequacies of Bragg’s battle plan. On the 31st, Breckinridge relayed reports intimating that there was a large Federal force massing for an attack on the eastern side of Stones River. This was untrue, and would have been discredited if Breckinridge had conducted proper reconnaissance. This information was finally proved wrong late in the morning and Bragg ordered Breckinridge to join the main line on the western side of the river. Before Breckinridge redeployed, however, a courier arrived bearing word that another Union column was advancing east of the river. Breckinridge was halted again while this report was investigated and invalidated. Despite the ferocity of the first day’s assault, it was diluted by false information. Bragg’s decision to set up a headquarters far removed from the battlefield further added to the tactical confusion. After the December 31 fighting, Confederate cavalry operating in the Union rear reported that Rosecrans’s army was preparing to retreat. Bragg was only too willing to believe this news, and he confidently withheld a new assault and waited to take possession of an uncontested field. Instead, Rosecrans stayed in place and assembled fresh reinforcements. Bragg’s position became untenable in the face of this new concentration.

Fact #7: Breckinridge’s charge on January 2 was one of the most violent charges of the war.

The armies spent January 1 dressing their lines and tending to their wounded. Rosecrans, now holding a tight position with both flanks joined to Stones River, decided to extend his flank across to the eastern bank. Bragg responded by ordering Breckinridge to charge and pulverize this new position. If the charge was successful then Rosecrans’s rear would be exposed to a devastating artillery crossfire that could support a new attack in the western sector of the field. Breckinridge sent his men forward at 4 P.M. on January 2. Approximately 5,000 Confederates crossed half a mile of open field, torn from front and flank by massed artillery, and nearly broke the Union line in a desperate charge. Only a hasty shifting of reinforcements protected Rosecrans’s position. Over 1,800 attackers became casualties, roughly 36% of Breckinridge’s total force. This places the charge at Stones River behind only Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg in terms of attacker casualty percentage.

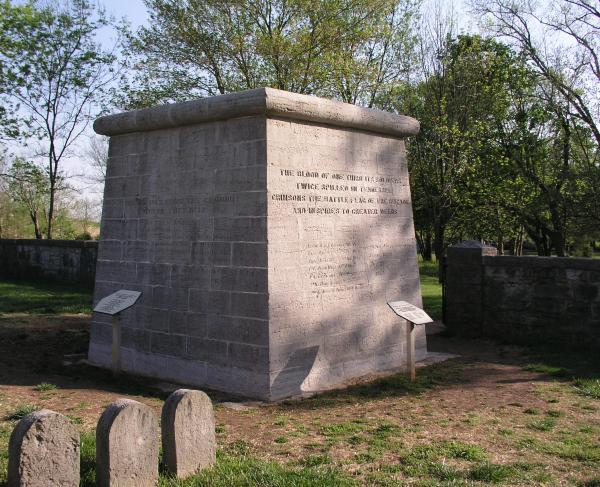

Fact #8: The casualty percentage at the Battle of Stones River was second only to the Battle of Gettysburg in all of the major engagements of the Civil War.

Throughout five days of battle, the most intense being December 31 and January 2, the National Park Service claims that nearly 24,000 men on both sides became casualties out of 81,000 engaged—a 29% casualty rate. Gettysburg had a casualty rate of 31%. Chickamauga, Shiloh, and Antietam had casualty rates of 29%, 26%, and 18%, respectively. The staggering losses at Stones River compelled both armies to spend months trying to regain their strength and come to terms with the causes of the winter bloodshed.

Fact #9: The Battle of Stones River was a tactical draw, but a strategic Union victory.

Bragg’s disinclination to renew the Confederate attack on January 1 allowed Rosecrans to strengthen his position and receive reinforcements. In fairness, if Bragg had attacked on New Year’s Day, he had no guarantee of success. His battle plan had achieved its objectives but not its goal—the Union army still held a strong defensive position. After the failed charge on January 2, Bragg realized that he could not win another fight against Rosecrans’s strengthened army and elected to retreat back to Tullahoma, Tennessee. Since neither side had swept the other from the field, the battle was a draw. In the weeks that followed, however, it began to take the shape of a Union victory. The somewhat positive result of Bragg’s unforced retreat provided an important boost to Northern morale, turned international opinion further against the Confederacy, and solidified the Federal hold on Tennessee. Meanwhile, Bragg left 10,000 irreplaceable veterans in the cold cedar forests and became the target of ridicule from his lieutenants as he bottled himself up for months in Tullahoma.

Fact #10: The Stones River Battlefield is threatened by development.

While the American Battlefield Trust has worked to protect Stones River, development continues to threaten this hallowed ground. Click here to learn more about the Trust's ongoing preservation efforts.

Test Your Knowledge

Learn More: The War in the West