Blackstock's Plantation

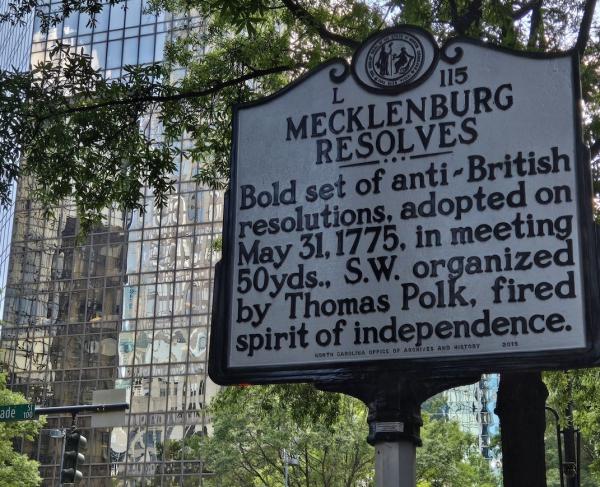

One of the more tragic aspects of the American Revolution was the struggle between Patriots and Loyalists that in many ways was truly a Civil War. The Southern Theatre of the war, in particular reflects this bitter partisan fighting as Patriot militia groups often found themselves going up against Loyalist brigades attached to the army of General Charles Lord Cornwallis. Cornwallis often leaned on the efforts of his most trusted and ablest subordinate, Banastre Tarleton, who consistently stoked the ire of the Patriots and fueled the emotions of the Loyalists.

By the Autumn of 1780 Loyalist forces were on the defensive in the Carolina’s still reeling from their stinging defeat at the battle of King’s Mountain in October 1780. With that Patriot victory the Carolina backcountry reverted to their control, putting additional pressure on Cornwallis and Tarleton. Thus rather than pursue the elusive “Swamp Fox” Patriot partisan leader Francis Marion, Cornwallis ordered Tarleton to harass Patriot militia units under the command of General Thomas Sumter. Cornwallis hoped that Tarleton could secure a victory and reinvigorate the Loyalist cause. By the end of November, 1780 Sumter’s partisan band swelled to 1,000 men strong.

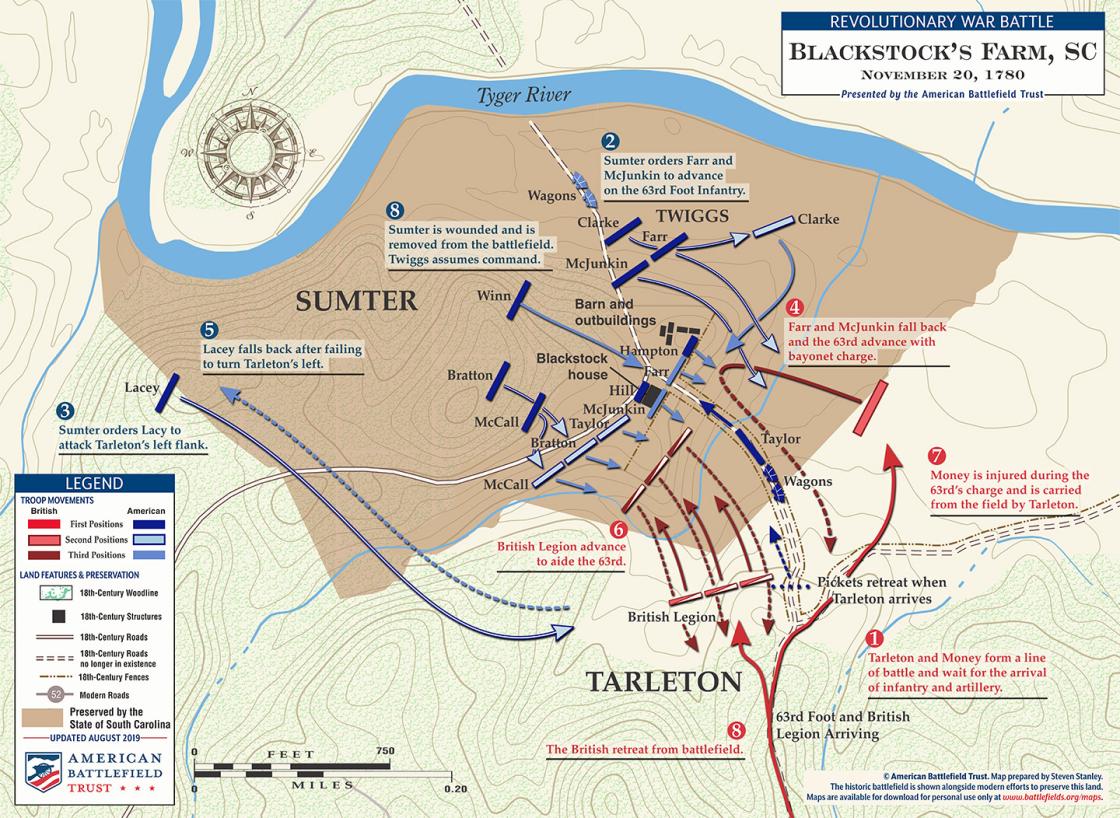

After a chance skirmish on November 18, as Tarleton and his men watered their horses at the Broad River Tarleton decided to press the issue and pursue Patriot forces that had fire on his men. Sumter was tipped off of Tarleton’s encampment and objectives. While the numbers seemed in Sumter’s favor under Tarleton’s command were several hundred British regulars. With the gathered intelligence in hand Sumter decided to bait Tarleton and set his men up in a strong defensive position on the farm of William Blackstock near Cross Anchor, South Carolina. The position afforded the Patriots with a clear field of fire as well as protection from stone walls and buildings.

Tarleton, who had yet to lose a fight, and who was always looking to flex his military muscle took the bait. It was a rash decision as he ordered a full frontal assault on Sumter’s position. Initially Tarleton’s forces had some success, even without artillery and his full complement of infantry, in flushing out defenders from their position. But the Patriots kept up their resolve and began to deliberately pick off officers a hallmark of militia tactics. As his close subordinates dropped around him Sumter’s men also were able to outflank Tarleton and attack his unsuspecting cavalry who had yet to be committed to the fight. With the tide turning against him Tarleton tried to regain the initiative at last employing his cavalry in a futile uphill attack. The well concealed Patriots poured a devastating fire into the onrushing cavalry which hastily beat a chaotic retreat as men and horses got tangled up with both beasts and men falling into a jumble blocking the road and route of escape.

As Sumter moved forward to watch the attack unfold he got too close to the fighting and was hit, sustaining a wound serious enough to hand over command to his subordinate.

Hoping to redeem himself the next day, Tarleton spent the night licking his wounds, but the pause gave the Patriots enough time to melt away into the backcountry. The battle was a tactical victory for Patriot forces.

In his after battle report to Cornwallis Tarleton’s ego got the best of him as he inflated his numbers while also reporting that he had pushed the Patriots off the field. Tarleton went so far as to say his troops, “promised to fix Sumter immediately.”

Sumter’s wound was a blessing in disguise, as Congress finally relented to permit George Washington to appoint his own choice for American command in the Southern department. In what was a fortuitous call for the Patriot cause, Washington appointed one of his best field commanders, Nathanael Greene, whose presence alone tipped the Southern campaign in the American’s favor.