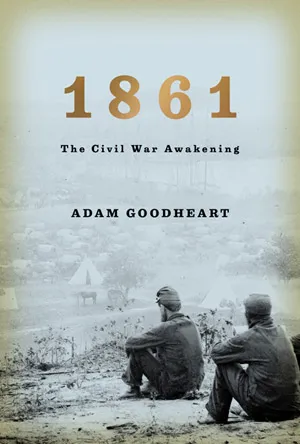

Book: 1861 - The Civil War Awakening

The Civil War Trust recently had an opportunity to sit down with Adam Goodheart, author of the national best seller 1861: The Civil War Awakening. In addition to receiving widespread praise for this new work, Adam is a longtime friend of the Trust and the author of the landmark April 2005 National Geographic article, "Saving Civil War Battlefields."

Civil War Trust: As compared to the typical Civil War fare of tactical battle accounts or biographies of prominent generals, your book really explores the unsettled emotions and reactions of the North as it confronted the prospects of a civil war. How did you choose this direction for your book?

Adam Goodheart: What first drew me in to the story was a discovery that I made about three years ago with the students in a class I teach at Washington College. We were exploring an old plantation house on the Eastern Shore of Maryland that has been in the same family for three hundred years, and up in the attic was a treasure trove of family documents spanning the 17th century through the 20th. It was just an amazing cache — unusual even for a place like the Eastern Shore, where the history and family history runs very, very deep.

In that attic, we found a bundle of letters that were from the spring of 1861, from a family member who was an officer in the U.S. Army, stationed out in Indian Territory — what is now Oklahoma — trying to decide which side he was going to join in the emerging conflict. He felt tied to Maryland and thus truly a Southerner, as well as coming from a slave-holding background. He was friends with Jefferson Davis — very close friends, almost family, to Jefferson Davis.

This officer had very close connections to the south, but also very strong loyalties to the United States, to the Stars and Stripes. He was being pulled both ways, and he was also being motivated by things like the question of what it would mean to his career or what it would mean to the future of himself, his family, his children. His wife wrote to him at one point, and she said, “It was like a great game of chance.”

Those words of hers really stayed with me and it really brought that moment alive. We tend look at history in retrospect; we have the story laid out in front of us. But at that moment, before the first shots were fired, there was enormous uncertainty about whether there would be a war at all. And if there were a war, how long would it be? Or what would be the price to be paid for reunion? What would be the price of Southern independence? If you signed on to the Rebel cause in the spring of 1861, would you be hailed as a hero to future generations, much as the patriots of 1776 were, or would you be hanged as a traitor from the nearest tree? Would you be participating in a brief and relatively bloodless but glorious struggle, or would you be marching off into the years-long slog of blood and mud and tragedy that we know now it turned into?

Of course, people had no presentiment at the time. The Spring of 1861 was a moment when the only certainty was complete uncertainty. It was a moment before the opening of the nightmare narrative that would take on a momentum of its own, the familiar litany of battles starting with Fort Sumter. These names of these battles - Manassas, Shiloh, Antietam and the rest - have such a power over us today; they form a kind of epic poem with a clear beginning, middle, and an end. But of course that was not something people knew in the spring of 1861. I was captivated by that uncertainty and by that feeling of not just an unfinished story, but an as-yet-unwritten story. And it seemed to me that by focusing on that moment and trying, to some degree at least, to push aside what we know about what happened later on, I could perhaps get into that moment in a new way

Your account seems to dispel the notion that the Northern population was slow to react to Southern secession and only begrudgingly decided to fight. Were Northerners really passionate about the war in early 1861?

AG: Despite all of the shifting of the historical landscape over the past few decades, moving away from the "Lost Cause" narrative and toward a much greater understanding of the central role that slavery played in the conflict, there is still this stereotype of the passionate, romantic South and an almost mechanistic North. There's that powerful but misleading image of the Union troops that Martin Scorsese put into "Gangs of New York," with Irish immigrants literally stepping off the boat and getting handed rifles and uniforms

Yet there was a real passion and a romance to the Union cause. And not just among the people that we might think of — the Abner Doubledays or the Joshua Chamberlains, that lofty sort of intellectual officer — but also among the ordinary men in the trenches, including immigrants. I found it very moving to read about, and have the opportunity to write about, the recent German immigrants who felt — perhaps even more passionately than some of the people whose ancestors who had been here for generations — that this was the land of liberty. They had come here for a certain kind of freedom, and they'd be damned if they would sacrifice that. They were ready to lay down their lives and fight for it.

I found that idea in some of the stories of the men in the casemates of Fort Sumter as the cannons thundered around them and the enemy's artillery rounds came crashing in. These were privates in the peacetime army, who were thought of by many contemporary Americans as just the dregs of the earth, grunts who were only there because they couldn't do anything better. Many of them were actually foreign citizens; one guy wrote about going right back to Ireland as soon as his enlistment was up. And yet he wrote about the thrill that he felt at seeing "our glorious Stars and Stripes," as he called it, waving over Fort Sumter and the pride he felt at their resistance to the Rebels and his feeling that they were fighting for freedom.

So there was a great romance, a great passion. It's even reflected in a way, I think, in the phrase that Southerners sometimes like to use: "the war of Northern aggression." It was actually a kind of war of Northern aggression; it was a war in which millions of Northerners, those who had stood up and voted for Lincoln, drew a line in the sand. They weren't simply trying to preserve the Union, as a lot of historians have argued. They were fighting for a particular kind of Union.

You draw a very interesting distinction about the motivations of the North at the outset of the war. You point out that for many Northerners in 1861 that the Civil War was a war against slavery, but not for abolition. How so?

AG: I think we tend, today, to conflate the two, antislavery and abolition. People say, "Lincoln wasn't so opposed to slavery, since he explicitly said he wasn’t fighting for abolition." And yet people in the 1850s and 1860s understood that these were two very different things. It's similar to how we deal with certain morally charged issues today; we're moved not only by moralism, but also by pragmatism. Especially in a democracy, you tend to think on the one hand about what is morally ideal, and on the other hand about what is practicable and what is going to enable our democracy to survive.

For instance, we have a lot of people today who feel very passionate about the environment, about trying to cut back the use of fossil fuels. As individuals, when they turn the ignition in their car, and that exhaust starts belching out, they know that they are doing something that may be having terrible consequences for the planet. And yet, almost nobody, I think, would be ready to ban fossil fuels outright today, despite the terrible consequences we know they may have.

I think a lot of white Americans felt that way about slavery in 1861. They knew that in a big, abstract moral sense it was wrong. I think the awareness was stronger and more immediate, actually, than with fossil fuels today. But I also think they knew that simply banning it outright overnight — although there were a few radical abolitionists who wanted to do that — would destroy the American economy in many respects. It would also disrupt things politically, upset the balance of American politics and quite possibly lead to violent civil war. It would be inconvenient and disruptive for whites in all sorts of ways.

Today, there are many people who aren’t ready to give up their cars, but say: "Well, let's at least start cutting back on our use of fossil fuels." They’re trying, at least, to move toward eventually rolling back or even eliminating them. I think there were people in the 1850s and 1860s who felt that way about slavery. When we see it in terms of people being either pro-slavery or pro-abolition, we really miss a lot — not just what the politics were, but what it was like to be alive in a nation that had slavery, what it was like to be alive in 1861.

Many whites from both the North and the South greatly feared the consequences of a major slave revolt at the start of the war. The fact that no major revolt happened had a powerful and positive effect upon Northerners. Why?

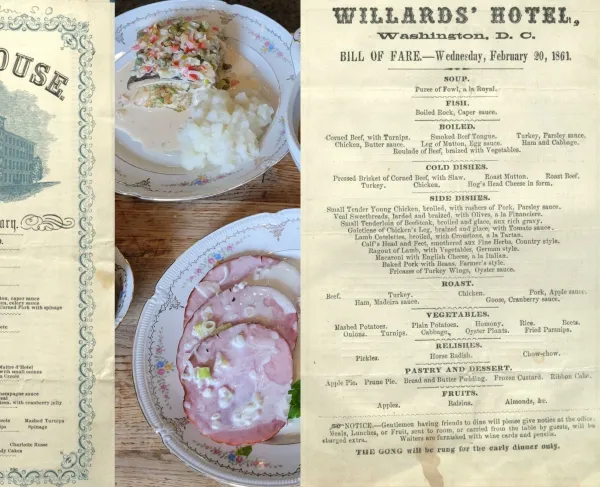

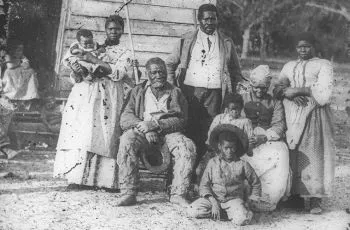

AG: On one hand, there were not any large-scale slave revolts. But on the other, there were large-scale slave defections almost from the moment that the war began. In fact, there's an account of a young African American who paddled in a canoe out to Fort Sumter several weeks before the attack, believing that these Union troops would give him shelter from the Southerners, would bestow his freedom upon him. He was sent back to his rebel master. But from that first moment that the war began, there were slaves who were talking about their freedom, feeling it in their grasp in a way that they had not before.

There were two astonishing surprises for white Americans. Before the war, there had been two big lies that many Southern slaveholders told themselves and the world. First: “Our slaves love us; they are devoted to us. They’re like our children and they wouldn’t want to be free.” But they had to pronounce another lie at the same time: “If we let the abolitionists come in here and stir things up at all — if we let the even the merest whisper of abolitionist sentiments be breathed below the Mason-Dixon line — our slaves could rise up in the middle of the night and murder us all in our beds.” They used those two myths to try to maintain their power over their slaves and also their power over United States politics. And what happened in the very first months of the war proved both those things wrong: the slaves were not going to rise up and murder their masters, but they all really wanted to be free.

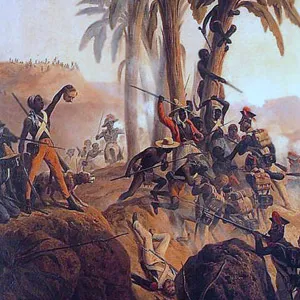

So, immediately, that told Northerners that by fighting the South they would not necessarily be setting off a black massacre of whites, or what was called “another Santo Domingo.” And, on the other hand, the response showed that, yes, these people are not just ready to be free, but they’re ready to be Americans and contribute to the Union cause, even put their lives on the line for it. That very quickly began changing the political landscape around abolition.

The crisis at Fort Sumter in April 1861 figures prominently in your account. You describe Major Robert Anderson, and one of the most important acts that he undertakes is to move is small garrison from the shore to Fort Sumter and how that was really such a pivotal decision. Why was that such an important movement and what impact did that have?

AG: Well, this was a moment when all across the South, Union troops were on the retreat; in place after place, federal forts simply dropped like ripe plums into the laps of the rebels. Anderson’s moving his men from Fort Moultrie to a stronger position at Fort Sumter was one of the very few acts of defiance on the part of federal troops at the beginning of the war —and it was an act of defiance that happened right at the epicenter of the rebel movement and the nascent Confederacy. This was a time when a lot of Northerners, and especially Northern Republicans, were really in despair. Anderson’s move was their one little rallying point; as the Buchanan administration just wimped out in many respects, and as so many officers of the Army were deserting to the Rebel cause, here was someone who was taking a stand for the Union. It became very symbolically important for the North. But, of course, it was also symbolic for the South, and so this little two-acre bump of land in the middle of Charleston Harbor became the grain of sand in the oyster of the Confederacy. It was an irritant that seems very small in retrospect, but they just couldn't stop chafing at it, so it became something more.

You also point out that when the Confederacy essentially took the first shot of the Civil War—they're the ones that started the bombardment of Fort Sumter— and that this action was a critical error. Why do you think that action, their precipitate attack against Fort Sumter, was such a key mistake?

AG: I think that so much of the narrative of the Rebel cause — both then and now — has to do with an idea of Northern aggression, that this wasn't a war that they welcomed, but rather something they were forced into. So the fact that they fired the first shot of the war really put the lie to that for many people. I think, perhaps most crucially, it put the lie to it for the European nations that they were looking to as potential allies, and who became much more wary of supporting what suddenly seemed like an aggressor nation. If Union troops had fired the first shot, it might have possibly gone the other way.

But also, it was a great strategic and moral error because it created America's first great "9/11 moment" or "Pearl Harbor moment." There was a visual — reproduced in Frank Leslie's and Harper's and elsewhere — of the Stars and Stripes flying proudly as artillery fire came crashing in around it. In the North, this was something that resonated on a deep emotional level with people, even those who had only recently been ready to make peace with the South. We've seen the same reaction with moments like Pearl Harbor, when there were a lot of people who wanted to keep the U.S. out of that war until the moment that Japan attacked. A very atavistic instinct kicks in at moments like that; you're ready to go off and fight for your country and old divisions disappear. That's what Fort Sumter did to the North. If Lincoln had been the one to order the first shot, I think those divisions would have only deepened and the Union cause might actually have fallen apart quite quickly.

You talk a lot about Major Robert Anderson and you point out that this was a man with a lot of Southern heritage—with a lot of Southern interests, family history, et cetera—and here he is at this central position at the most important place in the Civil War, at least the opening of the Civil War. Why would Lincoln have put someone in charge of this important fort who had such obvious Southern links or tendencies?

AG: It actually wasn't Lincoln who put him in charge of Fort Sumter. Anderson had been appointed just a matter of days before Lincoln's election by the Buchanan War Department and by Winfield Scott, the General-in-Chief of the Army. I think he had been appointed because he was a safe, moderate man. He wasn't the sort of person to stir up trouble either on behalf of the nascent rebellion or on behalf of the vehemently pro-Union and pro-Republican forces in the country. He was somebody from a border state; he sympathized with the South but was also extremely loyal to the Union; he was very predictable; he had sort of a quiet, methodical personality; so I think they saw him as being safe, perhaps even somewhat malleable.

You have a chapter in your book that talks about the truly divided nature of the State of California and the Far West. What did people like Jessie Benton Fremont and Thomas Starr King really do to keep California within the Union?

AG: You know, in this book I really tried to dispel the notion that the Civil War was just fought on a few hills and cornfields in Virginia, Tennessee, and Georgia. I very much wanted to show that the Civil War was also fought in thousands of communities and millions of families throughout the country.

At the outbreak of the American Civil War there was a serious debate about the course that California and the Far West would take. Many people out west were interested in separating into a Pacific Republic – a separate nation from the United States. This new nation would turn its back on the war in the east and face out onto the Pacific and its great potential.

The Civil War was really fought about the West, the future of America. Western expansion was one of the true flashpoints of the Civil War. The destiny of the west – slave or free soil – became a central issue as the United States continued to add western territories and states.

In my book I identified a few individuals who really epitomized this struggle for the future of California. The two characters that I focus on in California – Jessie Benton Fremont and Thomas Starr King – were two of my favorite characters in the book and really unlikely heroes in this struggle.

Jessie Benton Fremont, by virtue of being a woman and the wife of a prominent political figure, was someone who was not supposed to participate in political debate and statecraft. Despite these societal limitations, Jessie Fremont, an extraordinarily intellectual person, proved to be a remarkable political strategist. Her behind-the-scenes actions in support of the Union cause in California proved to be of great importance.

Thomas Starr King was perhaps an even less likely figure to play a major role in deciding the future of California. This pale, small, almost homunculus of a man, a Unitarian minister originally from Boston, had been very resistant to entering politics before arriving in California. But facing the real specter of secession, King and Jessie Benton Fremont soon became powerful partners working to keep California in the Union fold. Many people would later say that King was the man who saved California for the Union.

Fort Monroe plays an important part in your book — there's a lot of tremendous history there. There's been a lot of talk recently about the future state of the fort from a preservation point of view. What do you think is the historic importance of preserving Fort Monroe?

AG: Fort Monroe is an absolutely unique place. It’s a great American icon, almost on the level of Independence Hall or the Liberty Bell in the sense of what it means to our great national narrative of slavery, which is so central to the American story — from Jamestown to the present.

The fort has a lot to do with the entire arc of that story. Fort Monroe is located on Point Comfort, where, in 1619, the very first African slaves arrived in the English colonies. And also, by total coincidence, Fort Monroe is the place where the end of slavery began, where slavery received its deathblow.

In the spring of 1861, when three slaves escaped and crossed into the Union lines, they were given asylum at Fort Monroe. After that fateful moment, a tidal wave of "contrabands" followed in that first year of the Civil War. So, long before the issuance the Emancipation Proclamation took effect in 1863, tens or even hundreds of thousands of slaves were emancipating themselves at the Union-held Fort Monroe and elsewhere.

So Fort Monroe was where emancipation began, in May 1861. This may be an oversimplification of the narrative, but I think no more of an oversimplification than to state that American independence was born at Independence Hall in Philadelphia in July 1776. Thus, in terms of African slavery in America, Fort Monroe is both its birthplace and an ending place.

Remarkably enough, the site’s role in the establishment and ending of slavery in America — not to mention as the starting point of African-American history and culture — has been largely forgotten since the end of the Civil War. Right now it faces decommissioning by the Army after 400 years of being used as a military base, and its future fate hangs in the balance. I think it’s urgent now not only to rescue Fort Monroe, but to also tell its story, one that could and should be central to American history.

There are a lot of people in the United States today, whose ancestry does not track back to the Civil War-era, people from various nations that have come here post-Civil War. Do you think the American Civil War and the lessons of history, is it relevant to that group of Americans?

AG: Yes — I deliberately dedicated this book to my grandmother, who came from eastern Europe at the end of World War I, because she made American history ours too.

About one hundred million Americans, or one in three Americans, do have a Civil War soldier on the family tree, which is pretty remarkable. But I think this history very much belongs to all of us as Americans, because we are not a country in which nationality is defined by race or religion or ethnicity. We are a country where belonging is defined by stories; is defined by history; is defined by words and principles that we are all committed to. The Civil War was the great test and expression of those principles, and the Civil War is also the great American story, in the same sense that the Aeneid was the great founding story of Rome. You know, it’s funny: all through early American literature, poets set out to write the great American epic. Joel Barlow, a very obscure figure, composed a book that he called "The Columbiad," very consciously modeled on the Iliad and the Aeneid. All these books totally tanked.

But we finally got our great American epic a generation or two later, in 1861, in the Civil War. The Aeneid was a poem that someone who lived in a Roman outpost in northern Britain could read, centuries after it was written, and it would make him feel more Roman. The Iliad was a story that someone living in Alexandria could read, a millennium after it was composed, to connect with the experience of being Greek. I think in that sense, although it is a bit of a cliché to call the Civil War the American Iliad, it is very true.

Buy the Book: "1861: The Civil War Awakening" is available from our Civil War Trust-Amazon Bookstore

Adam Goodheart is a historian, journalist, and travel writer. He is writing a regular column on the Civil War for The New York Times online. He has written for National Geographic, Outside, Smithsonian, The Atlantic, GQ, and The New York Times Magazine, among others, and has worked as an editor of the Op-Ed page of The New York Times. He is a book reviewer for The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, and the New York Observer. He lives in Washington, D.C., and on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, where he is director of Washington College’s C. V. Starr Center for the Study of the American Experience.