Book: Baptism of Fire

The Civil War Trust had an opportunity to talk with Eric Jacobson, noted Battle of Franklin scholar and author, about his new book, Baptism of Fire: The 44th Missouri, 175th Ohio, and 183rd Ohio at the Battle of Franklin.

Civil War Trust: There are a lot of interesting regiments to consider at the Battle of Franklin. How did you choose to write a book about the 44th Missouri, 175th Ohio, and 183rd Ohio infantry regiments?

Eric Jacobson: Because all three units occupy a particularly unique place in the history and context of the battle. None had been in combat, unlike the veterans who largely composed both armies, and all three ended up being involved in some of the battle’s worst fighting, helping to contend with the massive Confederate breakthrough that unfolded on both sides of Columbia Pike.

Unlike most of the other regiments at Franklin, these units seem pretty green. Tell us more about where these units were raised and why they hadn’t had much combat experience before Franklin.

EJ: The 44th Missouri was mostly raised in northwest Missouri, from places like Grundy County and Sullivan County and cities such as St. Joseph. The 175th Ohio troops came largely from the rural areas of south central Ohio, from counties like Brown and Highland and cities such as Hillsboro. The 183rd Ohio was almost entirely from the Cincinnati area, and many of the troops were German immigrants who hailed from the historic area known as Over-the-Rhine. The 44th Missouri and 175th Ohio had been raised in August and September and the 183rd Ohio mostly in October and November. In fact, some of the 183rd Ohio soldiers had just been mustered into service in mid-November. As a result, the late autumn of 1864 was the first chance for these units to be involved in combat of any sort.

As the weary soldiers of Schofield’s two corps filed into Franklin, where were these regiments placed and what was their intended role?

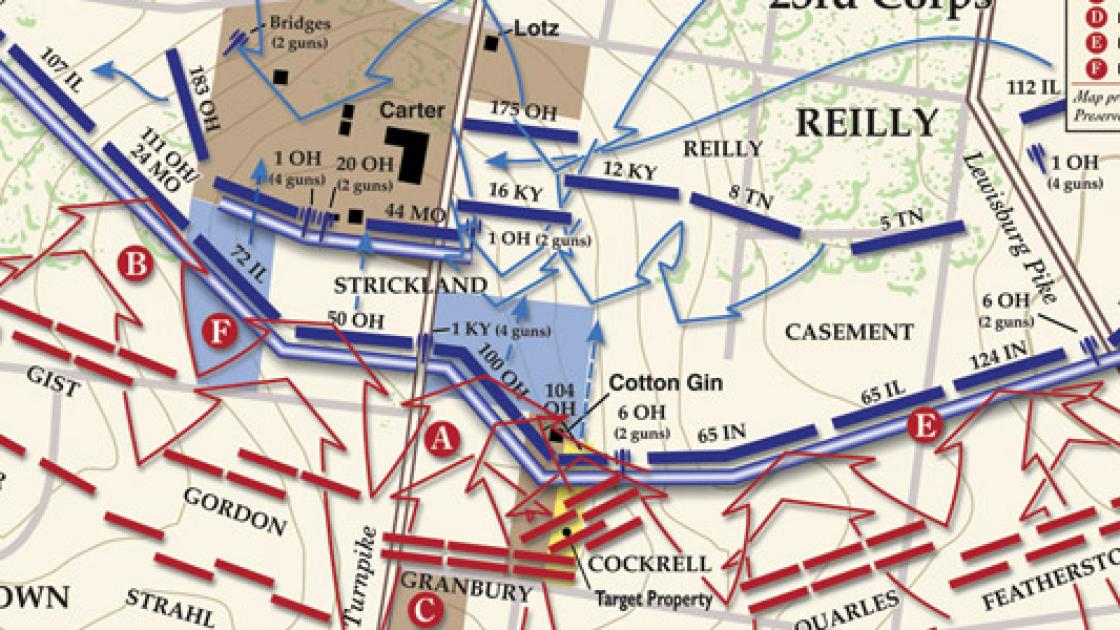

EJ: The 175th Ohio was not even attached to Schofield’s army and only found itself at Franklin because it moved north from Columbia with the rest of the Federal troops as they evacuated on November 29. It would be placed in a reserve position east of Columbia Pike, very near where the Lotz House stands today. The 44th Missouri and 183rd Ohio traveled south from Nashville to Columbia together on November 27 and then moved north together on November 29. When they arrived at Franklin around noon on November 30 they were placed into a reserve position west of Columbia Pike, with the Missourians forming up very near the Carter House.

With Confederate soldiers pouring through the Columbia Turnpike gap in the line, what sort of challenges and opportunities did the 44th Missouri face? What did this battlefield look like to them?

EJ: The challenges faced by the Missouri troops were immense. In addition to being exposed to combat for the first time, they were faced off against Maj. Gen. John Brown’s Confederates, who were some of the best troops in the Southern army. This was no easy task for certain, but through sheer force of will the 44th Missouri held together, even while under incredible pressure to prevent the Confederate breakthrough from expanding. For them the battlefield must have been a hellish scene. One man said the smoke was so thick he could barely breath and the Rebel troops came charging forward repeatedly, even long after dark.

What happened to the 183rd Ohio when the Confederates struck their position west of the Carter House?

EJ: The 183rd Ohio held a position that enabled them to support a section of the main line that was breached well to the west of the Carter House. Maj. Gen. William Bate’s troops briefly penetrated the main line near the locust grove, and upon seeing this Col. George Hoge moved his unit forward to help plug the gap that had developed between the 23rd Michigan and 129th Indiana. During this action Lt. Col. Mervin Clark of the 183rd Ohio was killed atop the main line of earthworks as he attempted to inspire his green troops.

Col. Emerson Opdyke and his brigade certainly have gained much of the credit for stopping and throwing back the Confederate breakthrough in the center, but you argue that maybe the praise heaped on Opdyke was a little much. Explain?

EJ: Far too much praise as the facts indicate. Opdycke was his own best promoter and he insisted, during the war and for years afterward, that his men alone had saved the Federal army at Franklin. The fact is, some 200 yards of the main Federal line collapsed during the initial Confederate attack, and Opdycke simply did not have enough men to plug such a massive breach. East of Columbia Pike, the 175th Ohio, along with the 12th Kentucky and 16th Kentucky, made the initial forward movement to help seal the breakthrough from the road to the Carter cotton gin. West of Columbia Pike, the 44th Missouri prevented the breakthrough from rolling up any more of the main line by serving as a check to the onrushing Confederates and throwing such fire into the Rebels that they simply could not sustain aggressive forward movements. These two phases of the battle bought a few precious minutes of time for Opdycke to move his men from their position some 200 yards north of the Carter House and helped fill the remaining gap in the line. Essentially, this was a true “team” effort and not accomplished by Opdycke’s men alone.

During your research you must have had the chance to delve into the lives of many of the soldiers who filled these ranks. Did you come away with any favorites?

EJ: So many rank and file stories came out that I couldn’t list them all, but I will say that Col. Robert Bradshaw of the 44th Missouri and Lt. Col. Dan McCoy of the 175th Ohio, who commanded their respective units, are particularly interesting. Most soldiers require proper instruction and need to know that their officers are fully committed. Bradshaw and McCoy instilled in their men the things necessary to withstand the fury of combat and truly led from the front. Both young men would be wounded at Franklin and both saw their units, in their only major combat experience, perform admirably.

For many of the 175th and 183rd Ohio that were captured, it seems that their post-capture experiences were almost worse than the battle itself.

EJ: Very true. All of them ended up at either Cahaba or Andersonville and some died there, but some of the survivors had the misfortune of ending up on the Sultana. Sadly, many more died when the Sultana exploded on the Mississippi River north of Memphis in late April 1865.

There’s been much work to save and reclaim portions of the Franklin battlefield. How much of the ground where these three regiments fought has been saved? And are there opportunities to save more ground around their positions?

EJ: Thanks to a great deal of hard work, and with so much help from the Civil War Trust, in just the past few years we have reclaimed some of the ground on which the 175th Ohio fought as well a portion of the Carter garden, where some of the men of the 44th Missouri battled and very likely the place where Col. Bradshaw was wounded.

Buy the Book: "Baptism of Fire" is available from our Civil War Trust-Amazon Bookstore

Eric Jacobson has been studying the American Civil War for nearly 25 years. A Minnesota native, Eric lived in Arizona for over a decade before relocating to Middle Tennessee in 2005. He is the author of For Cause & For Country: A Study of the Affair at Spring Hill and the Battle of Franklin, a project which encompassed nearly 10 years. Published in March 2006 the book is considered by some to be one of the most important books ever written about the 1864 Tennessee Campaign.

Eric’s second book, The McGavock Confederate Cemetery, was published in April 2007. He is currently the Chief Operating Officer and Historian for the Battle of Franklin Trust, which manages the Carter House and Carnton. His third book, entitled Baptism of Fire, which details the roles of three Federal regiments at the Battle of Franklin, was released in September 2011.

Eric lives in Spring Hill, Tennessee, with his wife, Nancy, and their two daughters.