Book: The Big Divide

The Big Divide, by Diane Eickhoff and Aaron Barnhart, explores the history, differences and cultural resources of the Missouri-Kansas borderlands. Their offering provides a portrait of this area though insightful reviews, thoughts and interesting facts about historic sites in the region. From the “Border War” to Fort Scott, readers will discover the immense and intricate history in America’s heartland, along with the long history of animosity between these two states, their peoples and struggle for identity.

Civil War Trust staff sat down with the authors to discuss the unique heritage they found while traveling this “line in the dirt.”

Civil War Trust: You’ve received some nice advanced praise for The Big Divide. Why do you think it is striking a chord with readers?

Aaron Barnhart: I think our timing is good. We’re catching that wave of scholarship that is recognizing the significance of the Civil War in the West. So there are some exciting developments that we were able to get into print before anyone else — like the State of Missouri dedicating a new battlefield site at Island Mound, where the soldiers of the First Kansas Colored militia were the first African Americans to fight for their freedom. That was in October of 1862, months before the 54th Massachusetts was even mustered in.

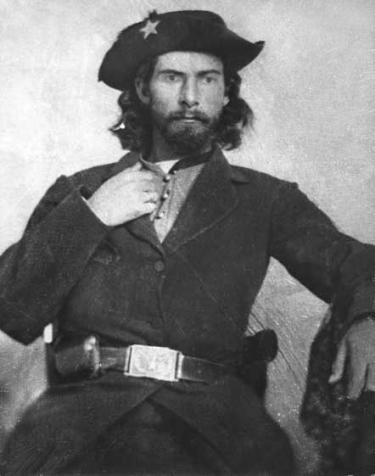

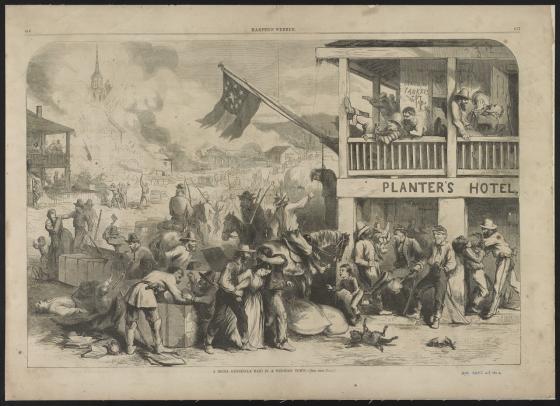

And today’s global war on terrorism has put the Civil War’s worst act of terrorism in a new light. I’m referring to Quantrill’s raid on Lawrence, Kansas, in August 1863, where 200 unarmed men and boys were killed in cold blood. This was immediately followed by one of the largest punitive actions in our history: when the Union Army ordered 20,000 Missourians out of their homes, which were then burned by the Jayhawkers.

The timing is good, especially since the recent explosion in the exploration of heritage tourism is a central theme of your book. Why do you think people are just now beginning to explore these historic sites?

AB: There’s a lot of big thinking going on right now. I think for many years there were these individual preservation efforts, and then it started to dawn on folks that by forming alliances they would raise awareness for all their sites. The Civil War Trust is a perfect example of that. By coming out to Vicksburg for its annual conference, for instance, the Trust is raising awareness about the battles fought outside the Eastern Theater. Other examples are National Heritage Areas, like Freedom’s Frontier, which covers the Missouri-Kansas border.

You're both from other regions of the country. What motivated you to travel the Kansas-Missouri border and discover the history of this region?

Diane Eickhoff: We moved here from Chicago 16 years ago so Aaron could take a job as television and media critic for the Kansas City Star. By happenstance, we bought a house that was two blocks from State Line Road, the dividing line between Missouri and Kansas.

Almost from the start we sensed there were longstanding resentments and distrust between longtime residents of both states. That was before we discovered that the whole region was a latter-day Bosnia. I discovered a little-known feminist who came to Kansas during the Bleeding Kansas era and after writing her biography, I ended up portraying her in 2004 for a Chautauqua sponsored by the Kansas Humanities Council. I began giving programs across Kansas for the Council with Aaron as my driver — I have low vision. We both were drawn into the drama of the Missouri-Kansas border. We even joined a troupe of reenactors who loudly debated the issues of the Border War era, which was a lot of fun.

When the U.S. Congress created Freedom’s Frontier National Heritage Area from 41 counties in Missouri and Kansas, it confirmed what we had already discovered for ourselves. There was a big story here — one that needed to be told from both sides of the state line.

The book is entitled The Big Divide, which relates to the differences in perspectives from Kansas to Missouri. What are the essential differences and how did they originate?

AB: It really all originates from the creation of something called the “permanent Indian boundary.” With the 1830 Indian Removal Act, the government begins moving dozens of Eastern Native American tribes to the territory west of Missouri’s border. It isn’t opened to white settlement until 1854. When it finally does open, an entirely different type of settler comes to Kansas than is living along the Missouri border. The Missourians are largely transplanted Southerners. The immigrants to Kansas mostly come from the lower Midwest. They aren’t exactly pro-black, but they have no love for the peculiar institution, either. So right from the start, these are two radically opposed groups of people.

Do the differences define this area, or is there something more?

DE: There are many layers of difference both between the two states and within them. Take Missouri, for example: during the Civil War, the state had two governors, neither of which was considered totally legitimate by large segments of the population. Like Kentucky, Missouri had a star on both the Union and Confederate flag. Residents of the state were deeply divided. Many on the western border and in the area called “Little Dixie” — south of the Missouri River — were from Southern states and identified as Southerners. They saw the Union army as an occupying force and supported the pro-South guerrillas, while others, especially German immigrants, supported the Union.

In Warrensburg, Mo., during the early months of 1861, Union and Confederate supporters drilled on the courthouse lawn on alternate days of the week. Some Missourians tried to stay neutral, but that wasn’t an option here. It was not so much brother against brother in Missouri. It was neighbor against neighbor, guerrillas posing as Union soldiers, Jayhawkers crossing the border to even old scores — general mayhem and misery.

Kansas had its tumultuous era in the seven years before the Civil War, but by the time of the Civil War, Kansas was solidly in and with the Union. Per capita, Kansas sent more soldiers to fight in the Civil War than any other state, but those living on the border during the war suffered also, both from fear of what might happen and from what did happen to a large number of communities. Yet internally, Kansas was fairly stable, while Missouri was in terrible turmoil.

Despite the tension and these vast differences, are there any important or striking similarities these states share?

AB: Well, today people in both states tend to vote Republican, and everyone here loves Kansas City barbecue. But one reason we wrote the book was to show that when Missourians and Kansans bring their stories of the Civil War together, the whole is bigger than the sum of the parts.

Most Kansans know that their ancestors were on the right side of history, so to speak, but they usually have no idea that many Missourians were staunchly supportive of the Union and suffered terribly for their support. We devote a fair amount of space in our book to Jesse James, because history has mostly gotten him wrong. He wasn’t a bandit who robbed from the rich. He came from a pro-Southern family that was tortured by the Union army. And his idea of revenge was to rob and kill his neighbors; people he knew were supportive of the Union during the Civil War.

What was the most meaningful site you visited in this book? Why?

DE: That would have to be the Pea Ridge National Military Parkin Garfield, Ark., just over the Missouri border. This is a magnificent battlefield, with extraordinary vistas and an excellent visitor center. Strategically, it was an important turning point in the battle for Union control of Missouri. With the help of good interpretation, it is astonishingly easy to imagine this battle during a brutal late winter storm.

AB: I’m a big fan of historic Lecompton, Kan. This was the territorial capital during the Bleeding Kansas years, and it’s here that a lot of people feel the match was struck that led to the Civil War. During the 1850s, there was a push by the Missouri faction to get Kansas admitted to the Union as a slave state. And so, they elected — by not-exactly legal methods — a pro-slavery legislature.

This body passed what was known as the Lecompton Constitution. And the only reason it wasn’t approved by Congress is that Stephen A. Douglas, the senator from Illinois and rival of Abraham Lincoln, knew full-well that this pro-slavery document did not have the support of the people of Kansas. So his group of Northern Democrats voted down the Lecompton Constitution. Kansas entered the Union as a free state, the Democratic Party split in two, and that’s how Lincoln won the 1860 election with only 40 percent of the popular vote. And they do a great job of telling that story in Lecompton.

Why do you believe the Kansas-Missouri border is the most consequential border in American history?

DE: The Missouri-Kansas border became the defining line for both Native American policy and for determining the future of slavery in this country. Who would own the land? Who would work it? I can’t imagine anything more consequential.

Exactly how important was this region to the Civil War and why?

DE: Out here we say that this region — not South Carolina — is where the Civil War really began. The seven-year Bleeding Kansas-era was a testing ground for the larger conflict and the bloody prelude to four hard years of all-out war. The Missouri-Kansas border was the place where compromise ended and both sides took their stand. When the larger war erupted it was unclear whether Missouri would stay with the Union. Her governor-turned-general might have succeeded in winning Missouri for the Confederacy had the leadership in Richmond supported his gains and held fast. For the Union, control of Missouri was imperative. With its large population, enormous natural resources, and — especially — access to and control of the Mississippi River, Missouri was critical to Union control of the region.

Which sites would you suggest a Civil War enthusiast visit first and why?

AB: I’d recommend making a beeline to southwest Missouri, around Springfield. Two of the nation’s 45 “Class A” battlefields are there, including Pea Ridge, just across the state line in Arkansas, where the Union Army wrested control of Missouri essentially for the rest of the war in 1862.

Wilson’s Creek, where the only major battle of 1861 besides First Manassas was fought, is a beautifully restored battlefield. And then just a short drive away is a terrific site that’s just emerging thanks to preservation efforts, at Newtonia, Mo. Ed Bearss has been a champion of Newtonia for years. It’s one of the few battles where opposing Indian regiments fought each other.

As interpretation of these sites continues, are there any new discoveries that have been revealed?

DE: Significant sites are being uncovered on both sides of the state line. We’ve already mentioned Island Mound and Newtonia in Missouri. Over in Kansas, the Black Jack Battlefield near Baldwin City is now acknowledged as the place where the first pitched battle of the Civil War occurred, five years before the guns began pounding Fort Sumter. This was where the abolitionist John Brown led a ragtag “army” of free-staters against a federal brigade, which was then supportive of the pro-slavery territorial legislature.

Ten years ago the land was put up for sale and a group of local preservationists quickly raised the money to buy it and then painstakingly restored it to its natural state as prairie. It was named a National Historic Landmark in 2012. The Friends of Black Jack have been absolutely heroic in developing this site and telling its story.

After reviewing and writing about more than 100 sites in your region, what qualities of a site provide for the best visitor experience?

AB: Site interpretation is crucial to the future of the Big Divide region. The best sites have modern signage, not too wordy, offering multiple points of view on what happened at that site, plus knowledgeable docents who can give guided tours. We always recommend that folks call ahead because historic sites are not theme parks, which are designed to give the same experience every minute they are open. You absolutely get a better experience with a guided tour.

That being said, the quality of the interpretation is key. The curators of these sites are battling a large perception, even among Kansans and Missourians, that all the major Civil War battles were fought out East. The reality is that if Governor Jackson had been successful in pulling Missouri into the Confederacy, it would have changed the entire nature of the war. General Scott’s “Anaconda” strategy was not designed to handle a powerful rogue state from the Trans-Mississippi region. Likewise, no one anticipated that guerrilla warfare would explode in 1863 after the Union Army occupied Missouri. No less than James McPherson has asserted that the guerrilla fighting along the Missouri-Kansas border was the worst in our nation’s history. It produced the greatest act of terrorism on our soil before 9/11. And then there was Sterling Price’s Missouri raid in 1864, which posed the greatest political threat to Abraham Lincoln in the weeks leading up to his re-election.

If you were to visit some of these sites 20 years ago, you might hear a local guide say something like, “So then the Yankees came in and burned our crops,” and that would be it! Missourians and Kansans have a big story to tell, but they have to tell it together, and they have to incorporate each others’ perspectives when they interpret their sites for guests. And they are doing it now. We were very impressed by the high level of interpretation, from National Park Service-run battlefields right down to the best county museums. Some sites still have a ways to go, and that’s where we come in, with our introductory essays in each chapter giving readers the whole story behind the sites and battlefields. But the reality is that if these sites weren’t doing their job, we couldn’t have done ours.

Buy the Book: "The Big Divide" is available from our Civil War Trust-Amazon Bookstore

Diane Eickhoff is a textbook editor turned historian. Her first book for Quindaro was Revolutionary Heart: The Life of Clarina Nichols and the Pioneering Crusade for Women’s Rights. She lectures regularly for the Kansas Humanities Council.

Aaron Barnhart is the former television and media critic for the Kansas City Star. He has contributed to the New York Times, Village Voice, CNN’s Reliable Sources, MSNBC’s Hardball, and Macworld. They live in Kansas City, Missouri — two blocks east of the Missouri-Kansas state line.