Book: Corinth 1862

The Civil War Trust recently had the opportunity to sit down with Tim Smith whose new book focuses on the 1862 Corinth Campaign. Tim is the author of a number of excellent Civil War histories focusing mainly on key battles of the Western Theater.

Civil War Trust: Tim, you have authored a number of excellent Civil War books. What attracted you to Corinth as the subject of your next book?

Tim Smith: Corinth fascinated me for several reasons. One, I grew up in Mississippi basically between Vicksburg and Shiloh and our family spent a lot of time at both. For some reason, Shiloh became my favorite battlefield, and over time I began to recognize that you can't really distinguish between Corinth and Shiloh. Their histories are so intertwined that one really can't be understood completely without the other. Second, I had ancestors wounded at Corinth, and a family connection always sparks interest. Other factors also contributed, such as my years of working at Shiloh and watching the development of (and then on occasion working at) the Corinth wing of the park. That nothing else had ever been done on the siege and occupation aspects also led me to look in those directions.

After the Battle of Shiloh, Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck declared that Richmond and Corinth were the keys to defeating the Confederacy. Richmond is easy to understand, but what made Corinth so equally important?

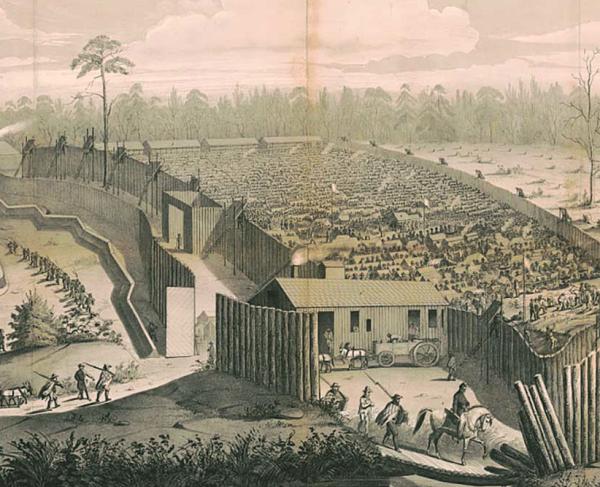

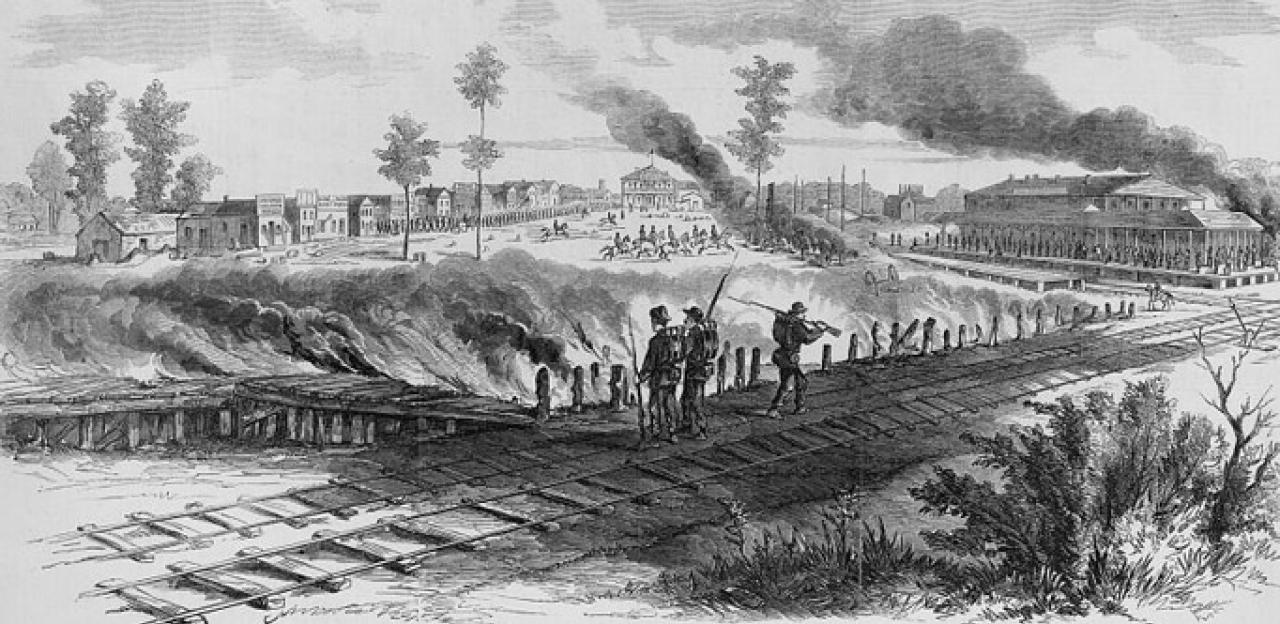

TS: It all revolved around the railroads. For better or worse, many historians have labeled the Civil War as the first modern war, and a lot of the reason is the advent of steam power, whether on water or rails. The two railroads that crossed at Corinth were two of the most important in the Confederacy, and certainly in the western Confederacy. The Mobile and Ohio was a major north-south route, but the Memphis and Charleston was the only complete link from the Mississippi Valley to the eastern seaboard. Jefferson Davis's first secretary of war termed these railroads the "vertebrae of the Confederacy," and they were just that – the logistical and transportation backbones of the South. Obviously, when war erupted, Corinth became a major strategic point to hold, and it developed into the major strategic point in the Mississippi Valley campaign. And I think we see easily the importance both sides placed on Corinth. At one point in the spring of 1862, both sides concentrated almost all their western resources, certainly their major field armies, on the Corinth front.

P.G.T. Beauregard seemed confident in his ability to hold Corinth, but there were growing problems in his ranks. How would you describe Beauregard’s forces leading into the Siege of Corinth?

TS: Beauregard knew he had to hold Corinth, and thus made the famous statement that "if defeated here we lose the Mississippi Valley, and probably our cause." But what he had to defend Corinth with was not very substantial. Having just come off of Shiloh, where he lost thousands of men and officers, he next had to face the potential loss of many of his units that had signed on for twelve months, or them remaining in the army but not being happy about it because the new conscription law extended their lengths of service. Plus, many of those who stayed were sick from the poor water in the area. And even the reinforcements who arrived were not in the best shape, troops such as those under Van Dorn who were poorly armed and had just come off a stinging defeat themselves.

After the fighting at Farmington on May 9, 1862, Henry Halleck became extremely cautious. Why was this?

TS: Halleck's communications to Washington and even his movements prior to Farmington displayed quickness, firmness, decisiveness, and an intention to get the job done quickly. He frequently made reference to fighting a big battle, and even told the War Department in early May that he would be at Corinth in a day or two. In fact, prior to Farmington there was very little of the entrenching we hear so much about; what there was of it basically took place on the open right flank of the armies as they advanced. Even more telling, his troops were making several miles a day in those early days, despite heavy rains, and were two thirds of the way to Corinth by May 9. But when Beauregard hit Pope at Farmington, Halleck seemed to lose his zeal. His messages turned to explaining his methodical and careful movements, and his men began to literally entrench every step of the way. So I see Farmington as crucial in altering Halleck's point of view, seemingly unnerving him a little.

Despite occupying Corinth, his objective, in May 1862, why was Halleck widely criticized in the Northern press?

TS: Because it was a bloodless victory that took a while to achieve. The public couldn't understand why it took so long if he didn't have to fight. But it was a lot more complex than that, of course. And I think we see this mentality elsewhere, even with Lincoln’s comment about Grant – "I can’t spare this man - he fights." I think if I were a soldier I'd be perfectly willing to take it slow and suffer fewer casualties, but ironically many of the ones complaining were the soldiers.

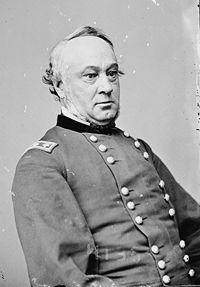

How did the Corinth campaign change after Halleck was promoted and transferred to Washington DC?

TS: It admittedly became the realm of second-rate officers, if we can call them that. Maybe second-tier is a better description. Obviously, Rosecrans would grow larger, but Bragg, Beauregard, Sherman, Grant, Thomas, Hardee, Polk, and others (in addition to Halleck) had all left by this time in one way or the other, leaving the operations under the second string, if you will – men like Sterling Price and Van Dorn with some name recognition, but with lower level commanders such as Thomas Davies, Thomas McKean, and Louis Hebert. Not exactly your Shermans, Hardees, or Braggs. That change is seen in the Union mentality of turning the theater into a defensive area as well. The first string was active elsewhere while these guys were just holding the line. But, or course, fighting erupted even among them.

With Corinth in Union hands, how would you describe Sterling Price and Earl Van Dorn's strategy to regain this strategic crossroads?

TS: Coming in from the northwest instead of the south or west was a complicated and ingenious idea, but it was based on speed and surprise. Unfortunately for Van Dorn, he was neither speedy nor did he surprise Rosecrans. So the Confederate plan was compromised from the start. The amazing thing is that the Confederates got as far as they did.

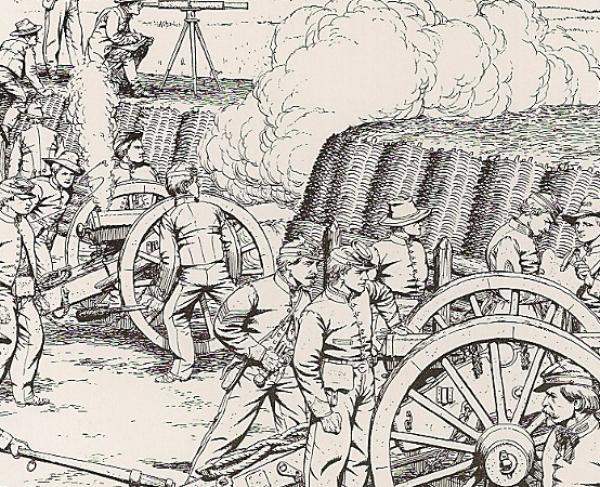

The Confederate attack on Corinth on October 4th met with much initial success, but why did it ultimately fail?

TS: Parts of the Confederate army did achieve their initial goals when Green took Battery Powell and Maury took Robinett, with elements of both divisions making their way into downtown Corinth. The reasons for defeat are pretty clear, though, including the fact that the attack that morning was delayed and the Federals were well prepared, that the Confederates had attacked all day the day before and were tiring, that ammunition was running low, that Van Dorn had not done a proper job of reconnaissance and thus knew nothing of the inner line of fortifications they would have to attack, and that heavy Union resistance from the earthworks before they fell took a lot out of the Confederate assault. More debatable was the lack of an attack from a third of the Confederate army under Mansfield Lovell. Some historians have exonerated him and others have really scolded him for not attacking. I fall more toward the latter, believing that even if his attack was doomed to fail, it was not his choice whether to obey. It was his duty to attack as well. And then, as I mention in the book, there is always the Missionary Ridge factor – that attack was perceived as doomed to failure but it worked. Lovell's attack conceivably could have somehow worked, but we’ll never know because he didn't try.

There has been so much positive and negative commentary on William Rosecran's generalship during the Second Battle of Corinth. Where do you come down on his performance at Corinth?

TS: After the battle, rumors flew all around that Rosecrans had run away, that he was a coward, and so on. While there were some curious activities on Rosecrans's part at Corinth, I nevertheless think he did pretty well overall. He had a plan, and that was much like Shiloh’s winning formula – falling back slowly during the first day, tiring the enemy out, and withdrawing to a strong last line where reinforcements (coming under James B. McPherson and E. O. C. Ord) could help him out. And it worked, so I think he fought a pretty good battle.

What can a visitor see of the 1862 Corinth battlefields today? Are there any great preservation opportunities at Corinth?

TS: Visitors can see some of the most amazing earthworks in the nation as well as most of the prominent sites. While Corinth's urbanization has destroyed parts of the battlefields unlike say Shiloh, there is still a large portion of it available for touring, and the new (I say new - 2004) interpretive center is first rate. And there is a lot of preservation potential over and above what the Trust has already done saving in the neighborhood of 715 acres there. The Trust, the NPS, and the locals at Corinth have done an amazing job, but there is so much more that could be done.

And what will your next book be on?

TS: I am currently working on a new history of the Battle of Shiloh. Stay tuned!

Buy the Book: "Corinth 1862" is available from our Civil War Trust-Amazon Bookstore

Dr. Timothy B. Smith, a former NPS ranger at Shiloh, teaches history at the University of Tennessee at Martin. He is the author of numerous books, the most recent being the new Corinth 1862: Siege, Battle, Occupation, published by the University Press of Kansas. He recently signed a contract with Kansas for a new book on Shiloh.