On November 23, 1765, Francis Bernard, the royal governor of Massachusetts posed this question in a letter in which the answer would result in blows ten years later between the colonies and the mother country.

“The question whether America shall or shall not be subject to the legislature of Great Britain..”

From that central question the British populace, Parliament, military, and monarchy would mull on as the decade of the 1760s turned to the 1770s and eventually as the proverbial “shots heard around the world” were fired in April 1775.

In the twelve years from the conclusion of the Seven Years War or French and Indian War as North Americans remembered it, the British Parliament, saddled with a huge war debt and the responsibility of administering the world’s largest empire at that time, levied new taxes and duties on their American brethren. Multiple ministers, five within the first ten years of King George III’s rule, plied their hand to these until finally, the king settled on Lord Frederick North in January 1770. North eventually served until 1782. The decrees from London enacted a series of measures, both peaceful and violent, between colonists and the British government. As the colonists split themselves, into pro-revolutionary and eventual independence supporters and loyalists as those who remained committed to the British crown and government were called, so too did British politicians and subjects pick sides.

Like their king, the British public initially hardened against the rebels in the colonies. After the Boston Tea Party, King George III wanted stronger more coercive measures against the colonists, perceiving that leniency in British regulation as the culprit of the escalating tension in North America. His stance in 1774 was to “withstand every attempt to weaken or impair” royal sovereign authority anywhere in the empire. The following year, he thought the “deluded Americans [should] feel the necessity of returning to their Duty” and in that regard declined to even lay eyes on the “Olive Branch Petition” sent by John Dickinson of Pennsylvania as a document asking for royal help to solve the differences between colonists and the British Parliament.

With the fighting that erupted in Massachusetts on April 19, 1775, a “Rubicon”, as the patriot John Adams called the change from words to bullets, was crossed. Hardening resolves on either side of the Atlantic caused the rupture to grow, with independence declared in Philadelphia and the stance of subduing the rebellion in London. With the popularity of newspapers and communiques, such as letters and dispatches, the British public was kept aware of the opening events in America; especially with the first shots at Lexington and Concord.

On July 22, 1776, the Third Duke of Portland received a letter from his wife in Nottinghamshire of “unpleasant news, that from America I trust in God is not true, it is really shocking.” The same duke received another type of letter from a fellow Englishman asking him to “preserve this country” and find a way to “cut Britain’s losses” with the war seeming to grow in North America. In the same vein but looking from a different perspective, an English author warned in pamphlet form that the loss of America would cut a swath into the British Empire and result in “inclosing us within the confined seas of England, Ireland, and Scotland.”

With a hardening resolve from the monarchy which was witnessed as well in Parliament, there was still, obviously, some of the British public that were anxious about hostilities between the colonies and the mother country. One set was merchants, who had a fair amount to lose with trade being disrupted by conflict. A group of Bristol, England merchants wrote to King George III in 1775 voicing their “most anxious apprehensions for ourselves and Posterity that we behold the growing distractions in America threaten” and ask for their majesty’s “Wisdom and Goodness” to save them from “a lasting and ruinous Civil War.” In addition, those of the working class of Britons viewed the affair in the North American colonies through a more positive prism and one that may usher in a new era for the world and possibly reform for their disenfranchisement.

The king would stay steadfast in his belief that war should be prosecuted until the colonies were subdued. Even after the defeat at Saratoga, New York in 1777, the entry of France which globalized the conflict, and even over the debates of his government officials to the contrary. In the king’s mind, ultimate victory in America was paramount to the very survival of the British Empire. However, as noted above, the same could not be said of all Britons, as some, like the Right Honorable Thomas Townshend had seen as early as October 1776, that “the Government and Majority have drawn us into a war, that in our opinions is unjust in its Principle and ruinous in its consequences.” Prophetic words at the opening stages of the long conflict.

After the defeat and capture of the British and Hessian force under General John Burgoyne at Saratoga, Lord North looked for ways to find an accommodation and end the war prior to France’s official entry, arguing that the war “would ruin her [Great Britain].” North tried resigning multiple times, but the king would not accept it, knowing that a replacement would have to be vetted through concessions to the opposition party, which would extract considerations to ending the war in America.

By 1780, there was unrest, both in Parliament and in the country in opposition for the continuance of the war and in rumblings of domestic reform at home. Even before the news of the disaster at Yorktown reached England, all the ministers in North’s cabinet, save one, Lord Germain, Secretary of State for America and in charge of prosecuting the war, were looking for a way to cut the losses and mediate an end to the war. He, with the backing of the king, still thought the war was winnable.

Members of Parliament, speaking for the opposition to the American war remarked by the summer months of 1781, that “opinion was that those who could understand were against the American war, as almost every man is now…” read James Boswell’s diary entry. Others attributed anti-continuation simply to the “majority of the rabble” which will “always be for the Opposition.” Historians now know that Boswell was more accurate and by the end of summer, William Pitt, the son of the former prime minister, with powerful words in support of a motion of Charles James Fox “into the management of the war in America” summed up the concerns in an impromptu speech in Parliament.

The younger Pitt stood up in the House of Commons and spoke in part with great passion:

“I am persuaded and I will affirm, that it is a most accursed, wicked, barbarous, cruel, unnatural, unjust, and most diabolical war…The expense of it has been enormous...and yet what has the British nation received in return? Nothing but a series of ineffective victories or severe defeats.

Even though Pitt’s remarks received praise from both sides of the issue, nothing changed and unfortunately for the peace movement, Fox’s motion was defeated. A “severe defeat” was needed to shake the resolve of the monarchy and his current government. By the time Parliament reconvened in November of that year, that “severe defeat” happened and just the time it took for news to cross the Atlantic Ocean kept the British from knowing it by that month. When the prime minister did receive the news, his reply is now well known, “Oh God! It is all over.” Apparently, the shock was akin to him having “taken a [musket] ball to the chest.”

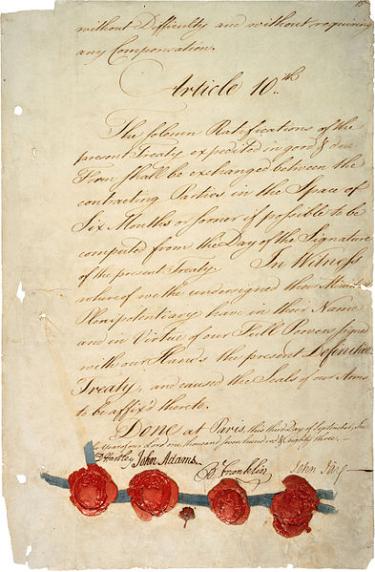

By March of 1782, Lord North’s ministry was coming to an end and although peace would not be fully cemented by treaty until the following year, the war was winding down in North America. Negotiators traveled to Paris, France, and began the discussions that would lead to American independence. On December 5, 1783, King George III gave a speech to the House of Lords in Parliament. Within that address, the king would have to mention the recently agreed-upon peace treaty. In attendance was a foreign representative to the French foreign minister. He would write later “in pronouncing independence the King of England did it in a constrained voice.”

The “constrained voice” is a good synopsis of how the British viewed the American Revolutionary War. From anxiety to a foreboding sense of the conflict being a civil war, to some admiration, and to a hardened resolve most present in their monarchy. The “constrained voice” furthermore would also symbolize the first decades of coexistence between Great Britain and her former colonies.

Further Reading

- The British Are Coming: The War for America, Lexington to Princeton, 1775-1777 By: Rick Atkinson

- The French and Indian War: Deciding the Fate of North America By: Walter R. Borneman

- American Rebels: How the Hancock, Adams, and Quincy Families Fanned the Flames of Revolution By: Nina Sankovitch

- American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750-1804 By: Alan Taylor