By noon on May 2, 1863, General Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson had been leading a long column of gray-clad troops through the woods for four hours. Nearly 30,000 men followed the legendary general on his secret route through the Wilderness of Spotsylvania County. The march to battle eventually would cover a dozen miles. Halfway to their goal, weary, dusty Confederates found a delightful treat in their path: drinkable water. The Wilderness abounds with wet spots. The murky, fetid, stagnant water in the marshy bottoms, however, is just about as far from potable as any liquid found in nature. Copperhead snakes seem to appreciate it; scrawny, unwholesome vegetables grow in it; humans must not drink it, and few are tempted.

Poplar Run, however, bisected Jackson's route with some downhill momentum. Cars following the flank march still splash through a rocky ford today. The U. S. Army, improving the road in the 1930s to accommodate tourists' automobiles, resisted the urge to throw a bridge across a stream that remains almost always fordable.

The sturdy infantry, whose rapid marches had earned them the nom de guerre "Jackson's Foot Cavalry," had fallen into poor condition during the winter. Desuetude had robbed their limbs of endurance. Wretched rations had brought on scurvy and other symptoms of vitamin deprivation. Men who had been able to cover twice the expected distance in 1862 struggled to keep up on May 2, 1863. Officers noticed veterans collapsing by the roadside; some even reported deaths from exertion. Drinkable water must have looked to the marchers as delicious as a Saharan oasis to a lost American soldier in North Africa in 1942. Uncoiling a mass of nearly 30,000 men onto narrow woods paths created a fantastic logistical tangle. When the march started, Jackson's corps had been clustered in camps that covered a compact zone. Near the end of the day, when the general finally had his attack ready to launch, that mighty array again would be deployed into a tight formation. All day long, however, all of those men and cannon had been in an alignment anything but compact. Jackson's entire corps for many hours had been four men wide and many miles long, forming a great gray serpent winding through the thickets.

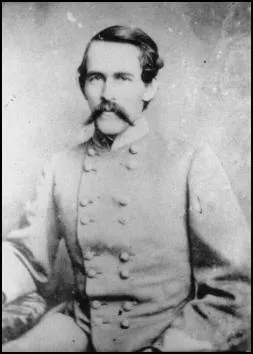

When he turned the march north onto Brock Road, not far beyond Poplar Run, Jackson thought that he was approaching his target, but the enemy's alignment did not conform to expectations. General Fitzhugh Lee, Robert E. Lee's nephew, was about to play an important role in reconnaissance.

Fitz Lee would become Virginia's governor after the war. In his later years, the former cavalry trooper spent more time at the feed trough than the exercise paddock, and grew immensely corpulent. When the state installed the first elevator in the capitol, Governor Lee sent a messenger to fetch a particular judge from another building to his office. When the jurist, whose shape resembled the governor's, arrived, Fitz admitted that his only purpose had been to make certain the newfangled contraption really would carry that much bulk without breaking down.

On May 2, 1863, trim young Fitz, a wounded veteran of the Indian wars, scouted ahead of Jackson's infantry column. At the Burton Farm on the Orange Plank Road, halfway between the Brock Road and Wilderness Church, he came upon a splendid vantage point that overlooked the enemy's lines. The view unfolded there made it obvious that Jackson must not turn east on the Plank Road to come into the Orange Turnpike at Wilderness Church. Federals stretched well west of the church on the Turnpike. Attacking there would not accomplish the goal of the whole risky march. It would mean falling upon the enemy head-on; not striking the exposed flank and rear. When Fitz guided Jackson to the hilltop vista, the corps commander recognized the salient facts at a glance. "His expression was one of intense interest," young Lee wrote. Jackson rasped orders to a courier for adjusting the line of march and, characteristically, rode away without so much as a word of thanks to Fitz Lee for his stellar efforts.

Back at the Brock Road, Stonewall Jackson scribbled a note to General Robert E. Lee, describing tersely the revisions he must make to the plan of attack. Despite the changes, Jackson remained as aggressive and optimistic as usual. "I hope as soon as practicable to attack," he told Lee.

As Jackson's column reached its final target, in the woods beyond and behind the enemy, clouds of Confederate skirmishers spread across the front to intercept any curious prowlers. The dense woods provided invaluable help in protecting the secret. Even so, the success with which Jackson maintained tactical surprise is astounding. Many Federals later swore — under the penetrating glow of hindsight — that they knew something ominous was afoot; but none of them did anything substantive about it.

Confederates who reached the designated front line on the Orange Turnpike swerved out to the right (south) or left (north), one brigade at a time in each direction. For a few seconds the whole front line included only the front marching file of four men as they arrived. Moments later there were eight, then hundreds, and finally thousands of them. A second division duplicated the formation at an interval behind the first. Eventually — after three hours of piling up regiments as they arrived — about 20,000 Confederates had arrayed themselves in long ranks in the brush.

Hindsight reveals something that Stonewall Jackson could not have known. He must have itched to launch the attack as soon as the front division had shaken itself into formation. Precious daylight dwindled while Jackson patiently steered the second division into line. He had come so very far, miles beyond any friendly assistance, that the attack must be successful — at once, and utterly overwhelmingly. The sun was sliding down the western horizon when Jackson finally had things the way he wanted them. A gamble at long odds, brought to fruition by a daylong, danger fraught march, had brought Stonewall to the brink of a rich dividend.

What, meanwhile, had the Federal commander, Joseph Hooker, been doing all through May 2? He had not been doing much of anything.

Hooker had led a mighty army into battle. During the last few days of April he had stolen a march on Lee, reaching Chancellorsville in good time and forcing the Confederates away from their powerful Fredericksburg position. On the night of May 1, Hooker had been full of bravado, issuing pronouncements dripping with gasconade.

Having achieved all of that, on May 2 Hooker spent most of a pleasant Saturday, in the midst of enemy country - not making good on his boasts, but instead simply dithering. Men around army headquarters that morning observed an air of confidence in Hooker's demeanor. A colonel described the army's commander as "in fine spirits and says our success is assured." Declaiming about such success was, of course, an entirely different thing than ensuring it.

Most of the Federal army succumbed to the lassitude emanating from headquarters. General Alpheus S. Williams of Michigan, Yale-graduated and 52 years old, had served in the Mexican War and energetically carved out a solid Civil War record. At corps headquarters, Williams found everyone, including corps commander Henry Slocum, sprawled about negligently. The generals and their aides and orderlies "formed a large group...all of us pretty much engaged in sleeping." While the Army of Northern Virginia put in one of the most active days in its storied history, the Army of the Potomac slept.

General Oliver Otis Howard's Eleventh Corps held a south-facing line that ran west beyond Wilderness Church to the far right of Hooker's army. It covered a mile and a half, on and near the turnpike. There the line ended, randomly, unprotected by any natural feature. Hooker had posted Howard far from the apparent center of operations because his corps seemed to be the least reliable, and contained the fewest men. A substantial number of the corps' soldiers came from German roots. Many had emigrated in the aftermath of the European upheavals of the 1840s; others had arrived in North America only recently.

The leaders of the Eleventh Corps reflected the composition of its regiments. Howard's subordinate commanders included men named Schurz, von Gilsa, Buschbeck, Schimmelfennig, von Steinwehr, and Krzyzanowski. Hooker and many others mistrusted these foreign-sounding fellows, many sporting unfamiliar accents and European modes of dress. Some of them deserved the mistrust, but others did not. Circumstances on May 2 would doom them all to participation in a crashing, thunderous disaster. In the aftermath, they absorbed more blame than the facts warranted.

The mounting evidence that Confederates were slipping west through the thickets persuaded Hooker - and many other Federals - that their enemies were doing what they wanted his flank them to do: retreat. An ironclad military maxim suggests that a commander should always expect his enemy to do what he should do. Wishful thinking does not work well in military equations, even though it is standard practice in political discourse.

At about 2:30, Hooker told a subordinate Lee was retreating "in the direction of Gordonsville." In preparation for pursuit on May 3, Hooker sent around orders to replenish supplies and "be ready to start at an early hour tomorrow." Howard later said that he joined "all the other officers" in believing the Confederate army was leaving the battlefield.

Along the lines of Howard's Eleventh Corps, afternoon shadows lengthened across a scene more indolent than militant. Soldiers butchered beeves, cooked supper, played cards, wrote letters, and loafed. Chasing the retreating Confederates in the morning might lead to action, but only after a quiet night. Then some thrashing in the thickets to westward began to draw attention. It soon became obvious that no one would be chasing Confederates anytime soon.

Eugene Blackford commanded a battalion of Alabama sharpshooters at Chancellorsville, but he was a native of Fredericksburg. On May 2, 1863, not long after 5 p.m., Major Blackford stood near Stonewall Jackson a dozen miles west of the major's birthplace. After three hours of arranging the arriving troops into long lines, preparations for a mighty surprise attack neared completion.

Confederates waiting to attack knew their march had accomplished spectacular results. They marveled that their prey, in Blackford's words, "knew nothing in the world of it" An Alabamian in the front rank wrote a few days later in apt summary: "when we stopped we were about three miles from [where] we had started. This is one of Jackson's moves." An artillerist also remarked on the typical nature of Stonewall's flanking march. The move was, he told his mother, "Jackson's old game."

As a final preparation, Major Blackford pushed his screen of skirmishers four hundred yards in front of the main line. One of them suddenly raised his rifle and fired. Blackford angrily "told him I would break his head if he fired again without seeing the enemy." The Alabama lad pointed out a solid line of Yankees lying down not fifty yards away. In the dense thickets, Blackford nearly had moved too far forward. A Louisianan in the second line called the groundcover "the thickest and most difficult bushes to get through I ever saw"

Before bugles and rifle shots and yells announced the Southern onslaught, wild animals burst out of the woods. Twenty thousand soldiers, tightly aligned, moving through dense brush, inevitably drove wildlife ahead of them. A member of the 23rd North Carolina wrote of his enemies: "the first intimation they had...was the rabbits and foxes running into where they were cooking." Fleeing wildlife puzzled and amused relaxing Federal soldiers. Bugle calls from the thickets soon clarified the deadly nature of the event.

Finally satisfied with his strength and alignments, Stonewall Jackson asked his leading division's commander, "Are you ready, General Rodes?" Rodes was ready. "You can go forward then." Rodes waved to Major Blackford, who turned to his bugler, Raif Grayson, of Sumter County Alabama. The brass instrument "had not sounded more than a note or two," Blackford wrote to his cousin, "when the whole line opened with a terrible yell."

One of the men yelling, Lieutenant Octavius A. Wiggins of North Carolina, described the sound echoing through the late afternoon as "that inimitable, unearthly, indescribable 'Rebel Yell' from the throats of twenty thousand veteran soldiers."

As the attacking ranks boiled out of the thickets, they found before them what a North Carolinian called "the grandest sight I have ever seen." Thousands of enemy soldiers were fleeing in disarray for their lives. A victorious Confederate wrote: "I reckon the Devil himself would have run with Jackson in his rear."

Through the last two hours of daylight, Confederates rampaged eastward toward Wilderness Church and then beyond. Everything went the Confederates' way, especially in the early moments as stunning surprise reigned in the Federal camps. The long gray lines "swept like an avalanche" through their foes, one of the attackers wrote. Captain William B. Haygood, commanding a company just south of the turnpike, described the opening of the attack in a letter to friends in Clarke County, Georgia. "We all then Sprang forwards," Haygood wrote, "with Such a Shout and yell mingled with a full round of minie balls, that they gave way at the first onset of our boys,"

Resistance by a few bravely desperate Northerners dissolved in short order. "We poured it into them and they to us for a short while," wrote Lieutenant Oliver Evans Mercer, of Brunswick County, North Carolina; "but soon we charged them and they fled like dogs leaving everything behind — knapsacks, trunks, arms...fat beeves already skinned." A Virginian situated near Jackson's left flank chose an ovine, rather than canine, parallel: "We [came] down on them like unto a thunder storm. They fled before us equal to sheep." A soldier from Huntsville, Alabama, opted for a harvest simile: "The enemy fled like chaff before the wind."

The fat cattle that caught Mercer's eye often appear as fond memories in descriptions of that afternoon. Many Confederates had eaten nothing for several days. Their frequent and rapid marches had outstripped the capacity of the army's commissary machinery. Even General Rodes, at the top of the food access chain, had complained that morning in a note to this wife that he was "very hungry indeed."

Famished men reveled in the chance to eat someone else's dinner. The soldiers "could not stop," an officer recalled, but "each man grabbed what he could and kept on. One man attempted to dispose of the whole of a beefsteak as he ran, and others drank at double-quick from the spouts of steaming coffee-pots."

Surprise unhinged the Federal line. Once that line began to dissolve, Southern pressure maintained the momentum. Those Federals who resisted stoutly had little to work with. Their original line faced the wrong way (south), and screeching enemies outflanked their main axis by up to a mile on either side.

"Now and then," an Alabamian wrote, "they would wheel a cannon into position, but before they could fire more than two shots we would be upon them." Comrades of William Whitaker of the 4th Georgia amused him by jumping atop captured cannon to "flap their arms and crow like a rooster!'

Naval officers dream of "crossing the T" on an enemy — catching their foe in a long straight line, while steaming across its top on a perpendicular axis (as at Cape Esperance in October 1942). In that fortunate alignment, the column "crossing the T" can fire all of its guns at the enemy, who can only respond with the front guns on the foremost ship. Jackson had "crossed the T" on Howard.

Henry B. Wood, from Coosa County, Alabama, summarized the attack in simple, unpolished prose. "We out don the northern hoards," Henry wrote on May 8. "We got them started and then kept it up."

An evening full of excitement and victory for Southerners offered no real options for Northerners other than brief resistance followed by flight. Troops never have tolerated surprise attacks from behind. Relative numbers and armaments dwindle in importance when an attacker achieves surprise and position.

The spectral image of Stonewall Jackson heightened the impact. "Jackson was on us," an Ohio soldier wrote, "and fear was on us." A colonel from Massachusetts drolly described his fleeing friends as "under the influence of an aversion for Stonewall Jackson."

Terrified Yankees "ran some one way and some another." In frightened attempts to hide, a North Carolinian wrote, "some of them ran in the tent and wrapped up in blankets." Captain J. W Williams of Greensboro, Alabama, described "a moving mass of yankees hundreds would turn and run to us to be taken prisoners." A Northern band must have been among the last to learn of the disaster: their boisterous tooting and thumping covered the noise of the initial onslaught, until a bullet shattered the bass drum.

Disintegration spread inexorably eastward. A French volunteer at Hooker's headquarters spotted the Eleventh Corps fugitives in "close-packed ranks rushing like legions of the damned" toward him. The Rebel yell unmanned the foreigner, who reported that "all of the [Confederates] roar like beasts."

Thousands of demoralized blue-clad troops scrambled through the woods toward Chancellorsville, then veered north for safety. Fugitives reached the Rappahannock River and thundered across the pontoon bridges, or swam the river. Indianan Henry Reed, an orderly to General Schimmelfennig, "flew to the rear," crossed the river, and only returned four days later. New Yorker Peter Bischoff returned to duty after an absence of three months. Ohioan William Devote took the opportunity to stay away from the army more than a year. Washington Swift, also from Ohio, fled on May 2 and reappeared five days later.

Colonel Edward L. Price of the 145th New York behaved in an egregiously unacceptable manner, according to witnesses at his trial under charges of "gross cowardice in the face of the enemy." The colonel became so "imbecile from fear that he couldn't find his way out of the woods," and demanded that "a drummer boy...show him the way." Price ran to a hospital beyond any danger, according to the testimony, and then hurried across the Rappahannock River and did not reappear for some time A surgeon testified that Price "said he had a tooth knocked out...which made him limp." The court somehow reached a verdict of not guilty, in the best tradition of American jurisprudence.

Northerners of sterner spirit put up the best fight they could, even under impossible circumstances. Neither General Carl Schutz nor 0.0. Howard displayed any discernible genius at Chancellorsville. Both men, however, bravely tried to rally troops. Howard mounted, tucked a flag under the stump of his missing arm (lost at Seven Pines in 1862), and desperately sought to rally a defense. An artillerist saw Schutz "with drawn saber endeavor to form a line."

The most famous Federal resistance on that afternoon came from a German-immigrant artillery officer, Captain Hubert Dilger. The captain had fine-tuned an Ohio battery, despite what he called "the intrigues & petit jealousies of the different german cliques" in the Eleventh Corps, and had become recognizable by the doeskin German-style britches he wore. When the Federal right collapsed, "Leatherbreeches" Dilger retired methodically down the turnpike, firing a single cannon in the road, then falling back and doing it again.

The Medal of Honor meant appreciably less during the Civil War than it came to signify for a time during the mid-20th century. It is impossible, however, to doubt that Captain Dilger richly deserved the honor, by the standards of any era. "Fought his guns until the enemy were upon him," the citation read, "then with one gun...he formed the rear guard and kept the enemy at bay by the rapidity of his fire and was the last man in the retreat." The devoutly Virginian historian who chronicled the history of Lee's artillery described Dilger's feat as "an example of almost superhuman courage and energy."

Despite the best efforts of brave men like Dilger, only darkness could halt the rout. In that darkness, some confused North Carolinians would do far more harm to Lee's army than any Federals had achieved on May 2. As Stonewall Jackson rode to the front of his triumphant corps to examine his options, he was approaching the site of his mortal wounding.

Related Battles

17,304

13,460