154th New York Regimental Monument at Chancellorsville

For the soldiers of the 154th New York Volunteer Infantry and the other regiments of Col. Adolphus Buschbeck’s 1st Brigade, 2nd Division, XI Corps of the Army of the Potomac, the Spring 1863 campaign began on April 13. That morning, in accordance to orders received the previous day, the men cooked rations, broke their regimental winter camp near Stafford Court House, Virginia, and, leaving their knapsacks behind, marched to the west, in the direction of Hartwood Church. 1

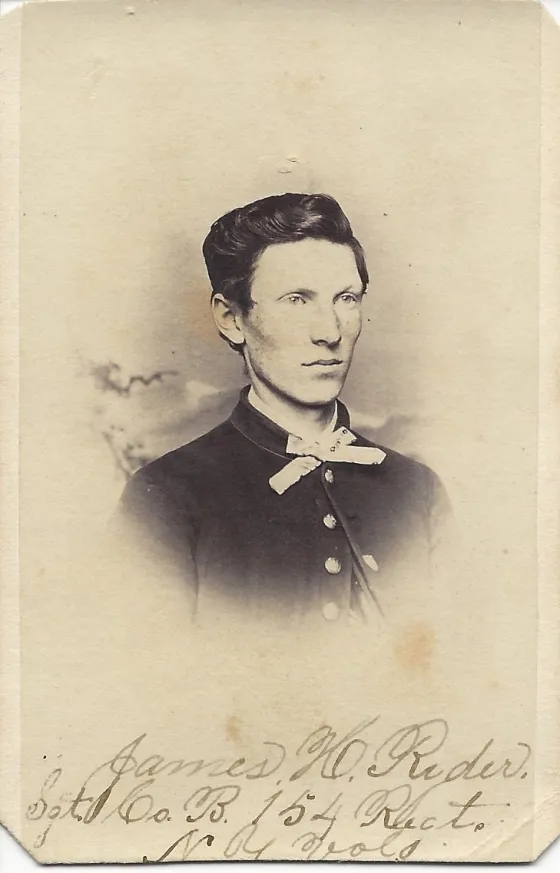

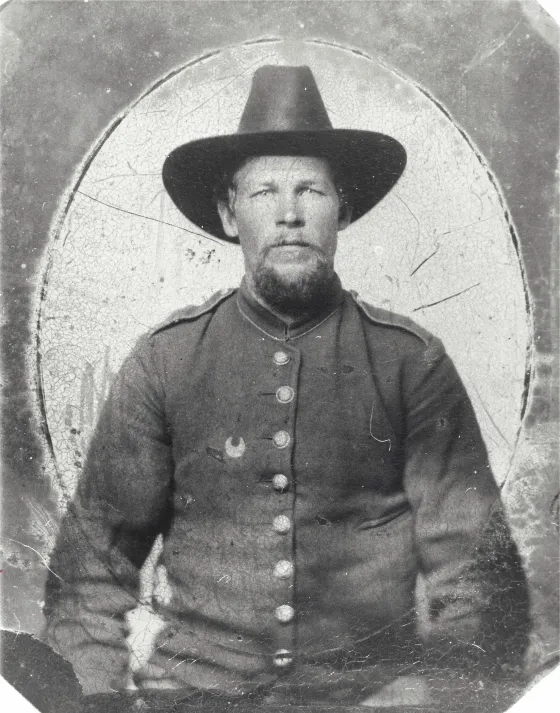

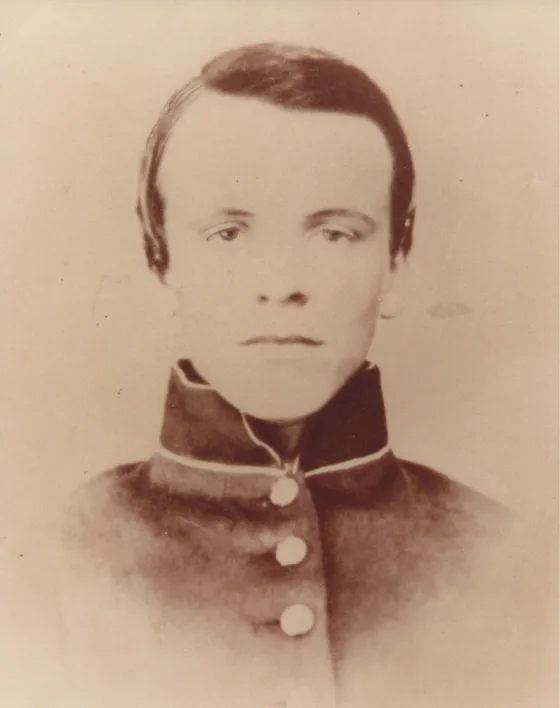

The 154th was a green regiment. Raised in the summer of 1862 in response to President Abraham Lincoln’s call for 300,000 three-year volunteers, eight of the regiment’s companies were recruited in Cattaraugus County, the remaining two in neighboring Chautauqua. Since its muster-in in September 1862, the regiment had journeyed by rail to Washington, D.C., been assigned to its brigade at Fairfax Court House, Virginia, made an inconsequential move to Thoroughfare Gap and back, marched to Falmouth and slogged along on the infamous Mud March, and occupied winter quarters in Falmouth and the camp near Stafford, named Camp John Manley after a civilian benefactor. After seven months of service, the soldiers of the 154th had yet to fire their Enfield rifled muskets in combat. 2

Just three days before the march commenced, on April 10, President Lincoln reviewed the XI Corps, a memorable occasion that inspired a flood of descriptive letters by the men to their homefolk. The pageantry capped a remarkable transformation in the Army of the Potomac. From its lowest ebb after the disastrous battle of Fredericksburg and the dismal Mud March under the command of Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside, a series of reforms by Burnside’s successor, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, had restored the army’s morale. One Hooker innovation—the adoption of badges to distinguish the various corps—had instilled a noteworthy unit esprit de corps. 3

Under the crescent badge of the XI Corps, however, all was not well. The composition of Buschbeck’s brigade was symptomatic of the corps’ affliction. Three veteran regiments were brigaded with the 154th New York. The 29th New York and 27th Pennsylvania regiments were composed of German immigrants and first-generation German Americans from New York City and Philadelphia, respectively; in the 73rd Pennsylvania, also from Philadelphia, English, Irish, and native-born Americans augmented a largely German core. The 154th New York was composed overwhelmingly of native-born Americans, primarily of British descent; only about 11 percent of the regiment’s members were foreign-born, and 3 percent German. The men of the 154th developed an antipathy toward their German cohorts, denigrating them as “damned Dutchmen.” According to Pvt. George W. Newcomb of Company K, the ethnic prejudice was mutual. “They are all Dutch in our brigade except our regiment,” he wrote, “and they do not like us very well. We can hardly get any water to use but what some Dutchman has washed his ass in it.” When the 154th men cheated the Germans by trading used coffee grounds for hardtack, the victims bestowed a nickname on their antagonists: Hardtacks. The 154thers accepted the moniker with pride, and their unit became known as the Hardtack Regiment. 4

The ethnic strife was not isolated to Buschbeck’s brigade. It permeated the XI Corps and the entire army, residue of a strong strain of antebellum nativism and xenophobia. Fifteen of the XI Corps’ 27 infantry regiments were composed primarily of German Americans. They differed from so-called American regiments in the language they spoke, the beer they imbibed, the food they consumed, the music they enjoyed, and their religious beliefs. Consequently the rest of the army had a low opinion of the XI Corps. Well aware of its looked-down-upon status, the German element of the corps suffered an additional blow to its morale on April 2, when the pious Maj. Gen. Oliver Otis Howard replaced as corps commander Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel, who was beloved by his German compatriots. On the eve of the spring campaign, the XI Corps was a troubled unit. 5

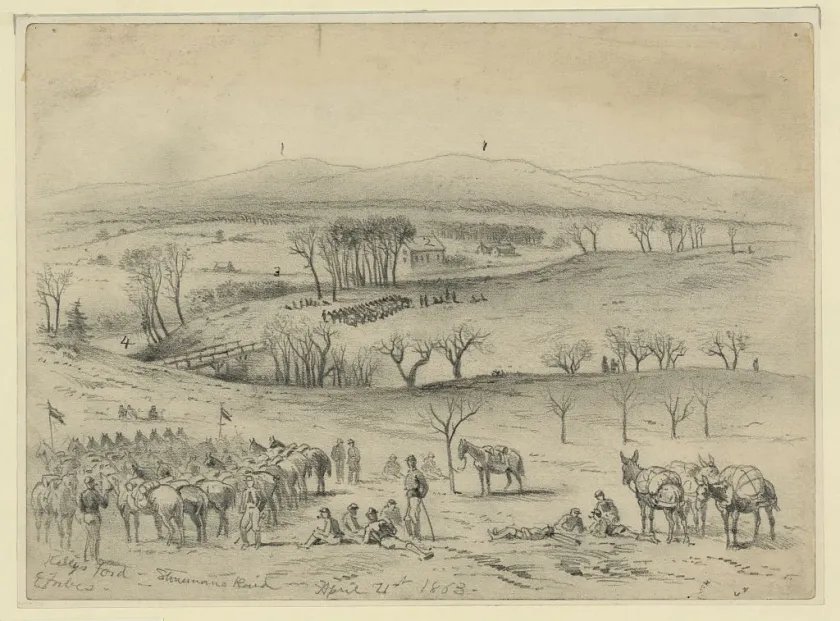

The march to Hartwood Church was uneventful. Regimental diarists reported the roads were in good condition; they estimated the distance covered at 12 to 18 miles. They found Hartwood Church badly vandalized, its windows broken, pulpit and pews gone, and walls covered with graffiti. Birds and squirrels had made the sanctuary their home. The men struck tents at daybreak on April 14 and marched another 15 to 18 miles to a bluff overlooking Kelly’s Ford on the Rappahannock River, where they camped near Mount Holly Church. A Confederate camp was visible on the opposite shore. 6

Buschbeck’s brigade was sent to Kelly’s Ford to support the cavalry divisions of Maj. Gen. George Stoneman, which were to cross the river at Rappahannock Station, five miles upriver, and make a raid in the rear of Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Confederate army. But a heavy rain fell the night after Buschbeck’s brigade arrived at the ford and continued for more than 24 hours. The high water caused Stoneman to postpone his movement, much to Gen Hooker’s disappointment. Harking back to Burnside’s Mud March, Sgt. Stephen Welch of Company C described the situation as “the 2nd stick-in-the-mud expedition.” 7

Contrary to the soldiers’ expectations, Buschbeck’s brigade remained at Kelly’s Ford for two weeks, picketing the riverbank and foraging the neighboring countryside for sheep, pigs, and chickens. “Live pretty well at the expense of the Secesh,” Sgt. Alexander Bird of Company G observed. Several of the Hardtacks were arrested and court-martialed for foraging outside the picket lines. Twice Colonel Buschbeck drilled the brigade, leading to more anti-German comments by certain Hardtacks. “Don’t understand Dutch orders,” Sergeant Bird wrote, “consequently don’t mind very good. Rather slow to execute.” During their free time the men played baseball and cards. On April 24, Pvt. Reuben R. Ogden of Company E recorded, “Helped take a drowned Reb out of the river.” 8

From its bluff-top camp and riverside picket posts, the soldiers caught glimpses of the enemy across the river. Surgeon Henry Van Aernam and Pvt. Emory Sweetland of Company B went down to the riverbank and scrutinized the Confederates through a telescope. Sweetland described them as “a hard-looking set,” not in uniform but rather dressed in a motley assortment of old gray clothes. They reminded him of tramps. Several of the men conversed with their Confederate counterparts. Corporal William H. H. Campbell of Company A had a nighttime talk with a North Carolinian picketing the other shore and the two parted wishing each other well. 9

Twice during the stay at Kelly’s Ford Buschbeck’s brigade was roused by false alarms of an enemy advance across the river. Called into line of battle at 4 a.m. on April 23, the men stood for an hour in a drenching rain before returning to their tents. Again, from 3 a.m. until daylight on April 26, they stood in a downpour, expecting a fight. Buschbeck rode along the line of battle and offered some words of encouragement to the untried 154th, which were recorded in an attempt to duplicate the colonel’s accent: “Now, poys, ven de enemy make de attack, you pe not afraid, but joost shtand prave und cool, und shoot ’em town joost like shickens.” 10

On April 27 the brigade wagon train arrived, accompanied by a number of convalescents and returnees from furloughs. They were given a warm welcome. A great scramble ensued as the men hunted for their knapsacks and delighted in mail from home and tobacco, of which they had been deprived since leaving Camp John Manley. 11

By April 28 it was apparent that something was afoot. That day great masses of troops arrived in the vicinity of Kelly’s Ford: the rest of the XI Corps, the V Corps, and XII Corps, together forming the right wing of the Army of the Potomac—this joint command headed by Maj. Gen. Henry W. Slocum. Hooker’s plan was for this wing to cross the Rappahannock at Kelly’s Ford, cross the Rapidan River, and march back eastward to the flank and rear of Lee’s army, while two of his other corps would cross the river and attack near Fredericksburg. The remaining two corps would serve as a mobile reserve, to be used where needed. 12

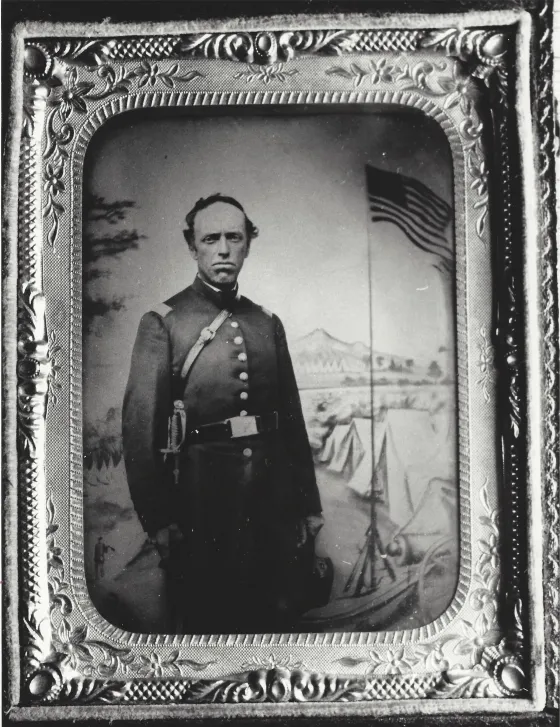

That afternoon it became clear that the 154th New York was to open the right wing’s advance. Colonel Patrick Henry Jones gathered his officers and informed them that the regiment was to cross the river in pontoon boats and clear the opposite shore of the enemy. The company commanders then relayed the orders to their men. About sundown the regiment, together with the 73rd Pennsylvania, boarded the boats in a Rappahannock tributary, Marsh Run, and paddled down the stream and across the river. The Confederate pickets got off a hasty volley that caused no harm. (According to a newspaper reporter, wet powder resulted in the Confederate pickets merely “snapping a few caps at the men in the boats.”) Most of the enemy fled; the 73rd Pennsylvania captured a group of them at a mill above the ford. After beaching their boats on the south shore, the Hardtacks climbed the riverbank, formed a line, and waited for the rest of the brigade to cross. Then they moved cautiously a bit farther inland and deployed to protect the laying of a pontoon bridge by the engineers. 13

The regiment remained in position for several hours until the bridge was assembled and another brigade crossed to take up the advance. The 154th then returned to the bridge, waited two hours for a break in the traffic, and crossed back to the north side and their recent campground, which they reached about 1 a.m. of April 29. 14

After a few hours of sleep, the soldiers were roused at 6 a.m., got breakfast, and about 8 a.m. marched to the river and crossed the Rappahannock for the third time. They moved about a half-mile inland, where they halted and stacked arms, and spent the rest of the day watching an uninterrupted passing stream of tens of thousands of men of the right wing, with their attendant horse-drawn artillery and mule-drawn trains. It was an impressive sight. “Have had a chance to see more than we ever have before,” wrote Stephen Welch. “What the destination of this vast body is, is of course only conjecture with us who are not of the council,” mused his Company C captain, Lewis D. Warner. “That it means work is certain and God speed the ball. The long-looked for move has at length commenced, and now the onward to Richmond I hope and trust is not to be a meaningless boast but a living reality.” 15

The regiment found itself on the plantation of the wealthy Mr. Kelly and proceeded to strip the place. Kelly, “who owns all the land within sight on both sides of the river,” according to Captain Warner, was “a rank secessionist” who had increased his riches supplying the Confederate army. Now the men looted “Kellyville,” as they called the complex, emptying his mill, his smokehouse, his store, his wheat fields, hay and grain, and “a house well filled with the comforts of life” including a set of fine china. “Kelly’s Ford will long remember the crossing of the Union army,” thought Stephen Welch. “So much for secession,” declared Captain Warner. 16

Now at the rear of the right wing’s long column accompanying the trains, the regiment marched at 6 a.m. on April 30 and covered more than 20 miles during the day. The first half of the march, on wet and slippery roads, took the men to Germanna Ford on the Rapidan River, which they reached around noon. There they took their midday meal and sat on the bank watching the trains ford the river, amused by the antics of the mules as they plunged and ducked in the swift, muddy water. The second half of the march, most of which followed a plank road, stretched from 5 p.m. to midnight, when the tired soldiers unburdened themselves of their heavy loads and slept on the ground without putting up tents. “About fagged out,” wrote Sgt. Horace Smith of Company D. “My feet badly blistered.” The men had penetrated the densely forested area known as the Wilderness. As they settled in for the night, General Howard complimented them for making such good time. That evening, General Hooker issued a general order to the army, in which he stated, “The operations of the last three days have determined that the enemy must either ingloriously fly, or come out from behind his defenses and give us battle on our own ground, where certain destruction awaits him.” The 154th New York’s bi-monthly muster rolls, signed that day, revealed 610 officers and enlisted men present for duty. Twenty were on detached duty elsewhere, leaving 590 men with the colors. 17

An early fog on May 1 gave way to a warm and pleasant day. The regiment spent the morning in camp. The men cleaned their guns and presented them for inspection. Around noon, they packed up to resume the march toward the enemy. They had not gone more than a half-mile, however, before they halted, about-faced, and returned to the starting point. Heavy firing could be heard from the front. The leading troops had run into the Confederates, who had not ingloriously flown but had put up enough resistance for Hooker to call off the advance. That afternoon the regiment dug rifle pits to protect its position. In the evening the firing grew closer in proximity and shells caused considerable commotion among the wagon train’s mules. The men lay on their arms as darkness fell. Work parties were engaged overnight in constructing entrenchments. “Our boys feel first rate,” Horace Smith noted. “We shall probably have some fighting to do tomorrow, but we are ready for them.” 18

Smith’s surmise was accurate. Lee had left a portion of his army at Fredericksburg to confront Hooker’s forces there. With the remainder of his troops, Lee had successfully stymied the advance of Hooker’s right wing. On the night of May 1-2, heeding reports from Confederate cavalry, Lee decided to further divide his army and send a force under Lt. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson to strike the unsupported right flank of Hooker’s right wing—the XI Corps. 19

At sunrise on May 2, General Hooker rode along the XI Corps lines and was greeted with loud cheers. After a breakfast of hardtack and coffee, the 154th New York moved into the rifle pits next to General Howard’s headquarters at Dowdall’s Tavern, the home of Melzi S. Chancellor, a Baptist minister, and his family. During the day rumors swirled that Stonewall Jackson, with a heavy force, was moving around the XI Corps’ flank. “We are expecting the ball to open every minute,” Horace Smith noted in his diary. Wrote Captain Warner, “Not much preparation, however, seems to have been made to receive him in our vicinity, except to place one or two batteries in position.” Around 3 p.m. the 2nd Division’s 2nd Brigade, commanded by Brig. Gen. Francis C. Barlow, left the lines to reinforce Maj. Gen. Daniel Sickles’ III Corps, which had moved from its own position to attack what turned out to be Jackson’s rear guard. General Howard and the 2nd Division commander, Brig. Gen. Adolph von Steinwehr, accompanied the brigade. Barlow’s was the largest brigade in the XI Corps. It would be sorely missed. 20

The 154th New York, together with the 73rd and 27th Pennsylvania regiments, held rifle pits south of the Orange Plank Road at Dowdall’s Tavern, facing south. The 29th New York was held in reserve north of the road. To the west, Maj. Gen. Carl Schurz’s 3rd Division was aligned along the Orange Turnpike, which split from the Plank Road in the vicinity of Wilderness Church, and in the fields north of the Pike spreading to the Hawkins Farm. West of Schurz’s men, the 1st Division, commanded by Brig. Gen. Charles Devens Jr., continued the line along the Turnpike to the Talley House and beyond. Most of the XI Corps’ line faced south, whence any potential attack was expected to come. At the far right of the line, two regiments and two companies of Devens’s division were placed at right angles to the Pike, facing west into the Wilderness and forming the extreme right flank of Hooker’s army. Less Barlow’s brigade, the XI Corps numbered approximately 10,500 men. Buschbeck’s brigade totaled about 1,800 men. 21

About 5 p.m. the soldiers of the 154th left their rifle pits to prepare their suppers. They never got to eat. As they cooked, the peace was shattered by Stonewall Jackson’s soon to be legendary surprise attack. Arrayed in three lines perpendicular to the Turnpike and extending about a mile on each side of it, the approximately 28,000 men of Jackson’s command burst from the woods, preceded by startled wildlife. Howling the rebel yell and firing volley after volley of musketry and round after round of artillery, they smashed Devens’s division to smithereens in a half-hour to an hour’s time and sent the survivors racing eastward. General Howard, who had returned to his headquarters at Dowdall’s Tavern just before the storm broke, rode west to a ridge and watched the rout with dismay. Clutching a national flag under the stump of his right arm (amputated after he was wounded at the battle of Fair Oaks), Howard tried in vain to rally the fleeing fugitives, streaming toward the Wilderness Church and beyond. “One may live through and remember impressions of those fatal moments,” the general later reflected, “but no pen or picture can catch and give the whole.” 22

The 3rd Division managed to mount a stouter resistance to the attack. General Schurz cobbled together a line stretching from the Turnpike northward to the Hawkins Farm, strengthened by some rallied elements from Devens’s shattered division and bolstered by artillery. But Schurz’s line, too thin and easily outflanked, was also sent reeling by the overwhelming onslaught, and fell back to Buschbeck’s position “like so many frightened sheep,” according to Pvt. George W. Newcomb of Company K. Some of Schurz’s men halted at Buschbeck’s position while others continued their flight. The time was about 6:30 p.m., around sunset. 23

For more than an hour, Buschbeck’s men had witnessed a steady stream of fugitives flow toward and then past their position, following the Plank Road to the rear. The routed men “fell back upon us in extreme confusion and disorder,” wrote Lt. Col. Henry C. Loomis in his official after-action report, “halting but momentarily then continuing their flight towards Chancellorsville.” Despite the interference, Buschbeck had plenty of time to realign his brigade to face the attack. He positioned his men in a shallow trench dug earlier by Barlow’s men that ran from the vicinity of Dowdall’s Tavern northward across the Plank Road into the field beyond. These defenses were shallow and built to face east rather than west, so offered little shelter to occupants. The 154th New York held the far left, near Dowdall’s Tavern. The 73rd Pennsylvania and 27th Pennsylvania extended the line to the right, and the 29th New York, together with rallied elements of Schurz’s and Devens’s divisions, occupied the pit north of the road. The so-called Buschbeck Line numbered between 4,000 and 5,000 men. Only one cannon—part of Capt. Hubert Dilger’s Battery I, 1st Ohio Light Artillery—stood with the infantry. Some of the corps’ artillery had been captured. The rest, including Dilger’s other guns and the reserve artillery, had been sent to the rear. 24

Here the Hardtack Regiment faced its baptism of fire under the most disadvantageous circumstances—holding the left flank of a small force, covering the demoralizing rout of its corps, and facing an enemy overwhelming in numbers, flushed with victory, and eager to destroy this last bit of opposition. Behind Buschbeck’s line, the Plank Road disappeared into the gloom of the Wilderness. It was more than a mile to the nearest Union reinforcements. 25

At the center of the regiment, Col. Patrick Henry Jones gave the order to fire at will and well-directed volleys slowed the Confederate advance. “I am pretty sure I laid out three of their men,” declared Cpl. Thomas R. Aldrich of Company B, “for I took good aim and they dropped.” He added, “I wish I could have killed a hundred.” Colonel Jones ordered the colors to be raised. The color-bearer, Sgt. Lewis Bishop of Company C, stood unprotected and waved the national flag in the face of the enemy. When a Confederate flag approached the regiment’s front, Lieutenant Colonel Loomis ordered his nearby men to bring it down. In response, Pvt. Edwin Ross of Company K stepped over the rifle pit, advanced ten or 15 yards, and shot the enemy color bearer, being wounded in the abdomen and elbow for his trouble. At the left of the 154th’s line, First Lt. and Adjutant Samuel C. Noyes Jr. stood atop the trench encouraging the men until he was shot and mortally wounded. 26

The Confederates swarmed the Buschbeck Line, according to Pvt. James D. Emmons of Company F, “like flies on a dead horse.” Several of the men later alleged that the enemy was drunk on a mixture of whiskey and gunpowder. Vastly outnumbered, outflanked both north and south, subjected to a murderous fire from front, sides, and rear, the Union line inevitably crumbled. The breakdown occurred from right to left, the rallied men of Devens and Schurz’s commands giving way first, together with the 29th New York and 27th Pennsylvania of Buschbeck’s brigade. The right battalion of the 73rd Pennsylvania joined the flight, but the remaining companies, seeing the 154th New York standing fast to their left, held on for a bit longer. Finally, realizing the regiment was in danger of being captured en masse, Colonel Jones, the highest ranked officer left on the XI Corps battlefield, gave the order to retreat. 27

The men had to cross an open field of about 800 feet before reaching the woods to their rear, which exposed them to a deadly fire that felled many. They left behind their dead and seriously wounded—including Colonel Jones, wounded in the hip—to fall into the Confederates’ hands. “Our regiment was the last that retreated,” wrote Thomas Aldrich, “and the Rebs weren’t four rods from me when I left [the rifle pit].” “When we was running,” wrote Pvt. Oscar M. Taylor of Company E, “our men fell like leaves.” With the enemy hot on their heels, the survivors plunged into the darkened woods, groping their way as best they could through the thick undergrowth toward the rest of the army, scattering into small groups, ridding themselves of knapsacks, haversacks, and canteens, some of them blundering into Confederate lines and becoming captives. 28

A core group remained with Lieutenant Colonel Loomis and rallied survivors to the colors during a brief halt at some vacant log breastworks erected by the XII Corps. Corporal Newell Burch of Company E went up and down the entrenchment and returned with several lost comrades. Lewis Bishop still held the national flag. The men counted more than 20 bullets holes in the banner, and three more balls had struck the flagstaff, one between Bishop’s hands, but the brave color bearer was unhurt. Loomis and his regimental remnant continued their retreat to the vicinity of Fairview, where they reported to General Sickles, who had returned from his afternoon foray. Sickles ordered the Hardtacks to the rear of his III Corps as a reserve, where they witnessed the ensuing night fight between that corps and the Confederates, now commanded by Maj. Gen. J. E. B. Stuart after the accidental wounding of Stonewall Jackson. There the 154th found the remainder of Buschbeck’s brigade. Around midnight the reunited command was ordered to the rear of General Hooker’s headquarters at Chancellorsville, where it spent the rest of the night. 29

Early on the morning of May 3 the XI Corps was moved to the left of the Union line, along the road running to United States Ford on the Rappahannock, where the disgraced corps was thought to be well out of harm’s way. While the core of the 154th New York lay quietly in its trenches about halfway between Chancellorsville and the ford, Capt. Matthew B. Cheney’s Company G saw more action. Cheney’s company had remained intact during the previous night’s retreat and picked up about 30 stray men from other companies along the way. They fell in with a division of the XII Corps and fought with that command during the heavy combat near the Chancellor house on May 3, during which several of Cheney’s men were killed, wounded, or captured. Late in the afternoon, having ascertained the XI Corps’ location, Cheney’s men rejoined the regiment on the River Road. 30

The rest of the regiment spent a quiet day. At one point a group of enemy prisoners were escorted past their position. One of the guards carried a captured Confederate flag. “Give me that rebel rag!” shouted one of the Hardtacks. A wounded young Confederate pointed toward the battle line and said, “There’s lots of them just up yonder, go and get one.” His remark caused a gale of laughter amongst Yank and Reb alike and silenced the smart aleck. 31

The men remained in the trenches on May 4. “Not much fighting this day,” Captain Warner observed in his diary. “Both sides seem appalled by the carnage of yesterday,” the second bloodiest day of the Civil War. On May 5 the regiment remained in the pits until 4 p.m., when it was relieved by the 29th New York and marched back a way to camp. Recalling the events of May 2, Horace Smith described the 29th as “cowardly” and stated, “How I would like to give them a volley of musketry from our guns.” A heavy downpour fell all night. “We were almost without shelter or blankets and no fires were allowed after dark,” Captain Warner wrote, “so you may suppose we passed anything but a comfortable night.” 32

Early on May 6, before the men had time to make coffee, they left the muddy breastworks and slipped and slid through the mire to United States Ford, where they crossed the Rappahannock via a pontoon bridge. Hooker’s entire right wing was retreating across the river, a movement that took the soldiers by surprise. “I never felt so depressed in my life,” remarked Surgeon Henry Van Aernam. The men marched for about ten miles and camped some two miles east of Hartwood Church. On May 7 they resumed the march and reached their old Camp John Manley at about 10 a.m. Finding the camp to be dilapidated, they fixed it up as best they could as the rain continued to fall. That night some of the men tapped a barrel of whiskey and got quite loud. 33

Camp John Manley was a depressing place, “very sorrowful and lonesome,” as Pvt. John Adam Smith of Company K described it. Huts that had once held four or five now had only one or two occupants, and some were entirely empty. The soldiers had embarked on the campaign with optimism; they finished it in bewilderment. The rout of the XI Corps was widely (albeit unfairly) blamed as the reason for the army’s defeat, and abuse was heaped on the unfortunate XI Corps men—particularly on the large German contingent—by the rest of the army. And the soldiers were stunned by the staggering losses. 34

The 154th New York took 590 men into battle at Chancellorsville and lost 29 killed, 9 mortally wounded, 42 wounded, 2 mortally wounded and captured, 37 wounded and captured, and 122 captured, for a total of 241 casualties. This amounted to a 40 percent loss rate, the fourth highest regimental casualty count in the entire Army of the Potomac. “The 154 has gained a name,” commented Sgt. Amos Humiston of Company C, “but at what a loss.” On Sunday, May 31, the men reflected on their fallen comrades when Chaplain Henry D. Lowing preached a sermon on the dead of Chancellorsville. “It was very good and appropriate,” commented Sgt. Samuel DeForest Woodford of Company I, “yet when he was enlarging upon the honors which they had gained by their gallant conduct upon the battlefield, . . . I could not help thinking of the many bereaved widows and helpless children that have been deprived of their husbands and fathers.” 35

Out of necessity, many of the regiment’s wounded were left behind during the retreat on May 2. They remained on the battlefield, receiving minimal but compassionate care from their captors. “Our men are as well cared for as the circumstances of the enemy, who have as many and more of their own wounded than they can well tend to, will admit,” Pvt. Colby M. Bryant of Company A, slightly wounded in the side, recorded in his diary. “I find there are many kind-hearted good men in the southern army, who for their kindness to me now while I am helpless in their hands have won my esteem and gratitude.” On May 12 the Confederates released the severely wounded into Union hands. They were transported to the division hospital at Brooks Station, not far from Camp John Manley. Emory Sweetland escorted them from United States Ford to the hospital. He noted that they “had not had much care” while in enemy hands, “and their wounds stank terribly and it made me sick.” On reaching the hospital, a number of them underwent amputations. 36

The Confederates marched the slightly wounded and unharmed prisoners of war to Guinea Station, Virginia, where they spent several days before proceeding to Richmond. There they spent a few nights in Libby Prison and on Belle Island, after which they were marched to City Point and paroled. They then boarded steamships and were transported to Annapolis, Maryland, where they had a short stay at the parole camp before being sent to the convalescent camp at Alexandria, Virginia. There they languished for several months before being exchanged and rejoining the regiment in Alabama, to which it had been transferred. 37

Despite the disparagement aimed at the XI Corps in the aftermath of the battle, various commentators praised the stand of Buschbeck’s brigade. As Cpl. Joel M. Bouton of Company C wrote, “Our brigade received all of the praise that the Eleventh Corps got.” A correspondent of the Philadelphia Inquirer wrote, “Amid the chaos and confusion of a flying corps one brigade alone stood its ground and fought until it would have been madness to have stayed longer; to them and them alone belongs the credit of saving the artillery and trains of the corps.” General Steinwehr, in his official report of the battle, stated that Buschbeck’s brigade “fought with great determination and courage” and withdrew “in perfect order.” After the war, higher commanders exaggerated Buschbeck’s stand. General Howard noted it realistically in a wartime letter to his wife, stating, “Some of Col. Buschbeck’s brigade stood and for some fifteen minutes held the enemy in check.” In the postwar years, however, Howard credited the brigade with quickly taking position on the reverse side of its entrenchments, holding the Confederates for more than an hour, and retreating in good order, facing the enemy the entire way. During a tour of the battlefield in 1876, General Hooker, who cited the rout of the XI Corps as a major reason for his defeat at Chancellorsville, stopped at Dowdall’s Tavern and stated, “Buschbeck’s brigade of that corps did wonders here, and held the whole impetuous onset of the enemy in check for an hour or more, which gave me opportunity to bring my reserves into position.” 38

Candid assessments by members of the 154th New York belie those claims. The Hardtacks admitted that Buschbeck’s brigade had stood for 20 minutes to a half-hour at the most, and that it had been routed like the rest of the XI Corps. They also asserted that half the brigade—specifically the 29th New York and 27th Pennsylvania—had fled before they did. That claim was upheld by the casualty figures for the brigade. The 154th suffered by far the heaviest loss (241 total), followed in descending order by the 73rd Pennsylvania (103), 29th New York (96), and 27th Pennsylvania (56). Captain Commodore Perry Vedder of Company H noted that when the men were driven from the earthworks, they went to the woods “on an accelerated run.” Private William Charles of Company F wrote, “Some of the boys acted like men but others acted very shameful. Some of the captains in this regiment ran as fast as ever they could and left their men to take care of themselves.” 39

The Hardtacks also took part in the faultfinding following the battle. Some assigned blame for the XI Corps’ rout on poor generalship, citing General Howard in particular. “Our officers were very much to blame in letting the rebels come on to us in the way they did,” asserted William Charles. “Curse such stupidity,” groused Pvt. Allen L. Robbins of Company K. “The criminal negligence of Gen. Howard was the cause of our defeat,” stated Pvt. Dwight Moore of Company H. Howard was “surprised in broad daylight,” First Sgt. James W. Bird of Company G wrote in the postwar years, adding the general “should have been cashiered.” Sergeant James M. Mathewson of Company K blamed the men, however, not their commanders. Many scorned the fighting quality of the Germans. “They are cowards,” judged Pvt. George Eugene Graves of Company D. 40

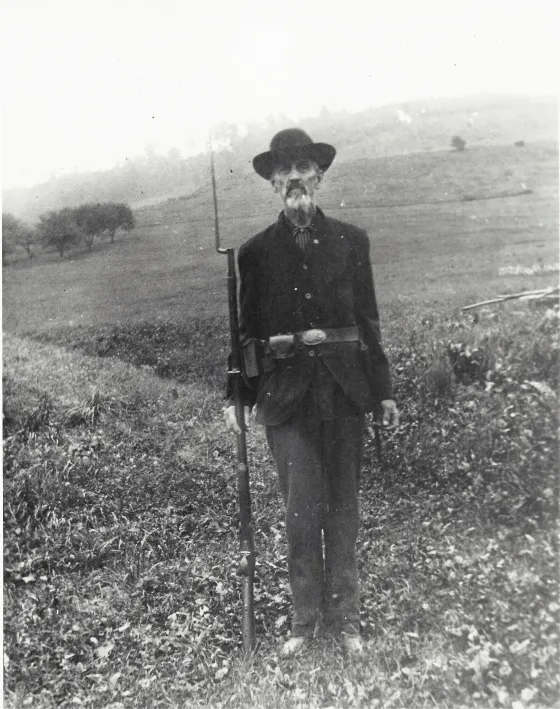

For the rest of their lives, Chancellorsville was a ready memory for the 154th New York’s survivors. An unhealed wound caused Pvt. Nathaniel S. Brown of Company D to wear a bandage above his right eye until he died in 1892. In 1893, Sgt. John F. Wellman of Company B commemorated the thirtieth anniversary of the battle in an epic poem. Quartermaster Sergeant Newton A. Chaffee offered vivid recollections of Chancellorsville in a Decoration Day address he delivered in 1896. First Sergeant Alfred W. Benson of Company H was continually reminded of the fight when he attended his Grand Army of the Republic post in Kansas, where his bloodstained jacket was displayed. (He had survived a gunshot wound through his left lung.) Recalling the battle in a memoir, Pvt. William D. Harper of Company F wrote, “May we hope and trust that our sons will never witness such a sight.” Forty-five years after they fought at Chancellorsville, brothers Alexander and James Bird visited the battlefield in 1908. “We readily recognized the different points on the field,” Bird wrote in an article for his hometown newspaper. “We had kept together during the two days’ battle, and the scenes we saw at that time were so indelibly graven on our memories that it seemed as if it were but yesterday.” Bird noted that the site of the Buschbeck Line was used as a pasture of a farm owned by a former Pennsylvanian, and that the battlefield was still littered with scraps of leather, cartridge box tins, brass belt plates, and bullets. Reflecting late in life on the regiment’s forlorn stand at Dowdall’s Tavern, Captain Lewis Warner summed it up succinctly, “The most unfortunate thing about the 154th was that we had not learned to run when we ought to have done so.” 41

Immediately following the battle, however, the Hardtacks voiced pride in their conduct during their baptism of fire. “The command behaved with all the firmness and unflinching bravery peculiar to the American soldier,” declared Lieutenant Colonel Loomis in his official report. “Every man proved himself a hero!” exclaimed First Lt. Alanson Crosby of Company D. “Our noble fellows stood until surrounded on three sides, and then withdrew under a murderous storm of bullets and shell.” “I am proud of the bravery, the heroism, and the valor of the 154th!” wrote Surgeon Henry Van Aernam. “Our ranks are thinned, but our name is untarnished.” “Nobly did the 154 respond to the call of duty,” stated Captain Warner, “and bravely did she sustain the credit of old Cattaraugus.” A number of the men used the same simile to describe the regiment’s bellicosity: “Our regiment fought like tigers and were all cut to pieces,” wrote Thomas Aldrich in one example. Aldrich, who received four wounds, added, “I tell you we had a hard place in the fight.” The men proudly reported that both Colonel Buschbeck and General Steinwehr praised the regiment for its stand. 42

That stand has not been forgotten. More than 130 years after the battle, motivated by knowledge of the regiment’s sacrifice, 136 descendants and friends of the 154th New York donated more than $5,000 to erect a regimental monument on the Chancellorsville battlefield. The crescent-shaped granite memorial stands south of and adjacent to the eastbound lanes of Route 3, about a mile west of the Chancellorsville Battlefield Visitor Center, at the edge of the field in which the regiment fought on the evening of May 2, 1863. Fifty-five descendants and friends, from as far away as California, attended the dedication of the monument on Memorial Day weekend in 1996. It is one of only three regimental monuments at Chancellorsville.43

Notes

- Mark H. Dunkelman and Michael J. Winey, The Hardtack Regiment: An Illustrated History of the 154th Regiment, New York State Infantry Volunteers (East Brunswick, NJ, 1981), 50-51; Horace Smith, Diary, April 13, 1863, Mazomanie (WI) Historical Society. Unless otherwise noted, all subsequent diary entries, letters, and newspaper articles cited are dated 1863.

- Dunkelman and Winey, The Hardtack Regiment, 21-47.

- Mark H. Dunkelman and Michael J. Winey, “The Hardtack Regiment Meets Lincoln,” in Lincoln Herald (Summer 1983), Vol. 85, No. 2, 95-99; Stephen W. Sears, Chancellorsville (New York, NY, 1996), 62-75, 80-82.

- Mark H. Dunkelman, “Hardtack and Sauerkraut Stew: Ethnic Tensions in the 154th New York Volunteers, Eleventh Corps, during the Civil War,” in Yearbook of German-American Studies (2001), Vol. 36, 69-90; George W. Newcomb to his wife, March 6, Lewis Leigh Collection, Book 36, #90, U.S. Army Military History Institute, Carlisle Barracks, PA (hereafter USAMHI). For better readability, spelling and punctuation have been corrected in quoting from soldiers’ writings.

- Dunkelman, “Hardtack and Sauerkraut Stew,” 70, 80; Christian B. Keller, Chancellorsville and the Germans: Nativism, Ethnicity, and Civil War Memory (New York, 2007), 10-15, 31-35, 44-48; Augustus Choate Hamlin, The Battle of Chancellorsville (Bangor, ME, 1896), 23, 31-32, 34; John J. Hennessy, “We Shall Make Richmond Howl: The Army of the Potomac on the Eve of Chancellorsville,” in Gary W. Gallagher, ed., Chancellorsville: The Battle and Its Aftermath (Chapel Hill, NC, 1996), 18, 23-25; A. Wilson Greene, “From Chancellorsville to Cemetery Hill: O. O. Howard and Eleventh Corps Leadership,” in Gary W. Gallagher, ed., The First Day at Gettysburg: Essays on Confederate and Union Leadership (Kent, OH, 1992), 58-61.

- H. Smith, Diary, April 13-14; John Adam Smith, Diary, April 13-14, courtesy of Georgia G. White and Donald J. Gould, South Dayton, NY; Stephen Welch, Diary, April 13-17, courtesy of Carolyn Stoltz, Tonawanda, NY; Colby M. Bryant, Diary, April 13-14, courtesy of Bruce H. Bryant, Salamanca, NY.; Lewis D. Warner, Diary, April 27, Portville (NY) Historical and Preservation Society; Reuben R. Ogden, Diary, April 16, courtesy of The Horse Soldier, Gettysburg, PA; “From the Army,” Cattaraugus Freeman (Ellicottville, NY), June 25, quoting letter of William H. H. Campbell, June 14.

- John Bigelow, Jr., The Campaign of Chancellorsville: A Strategic and Tactical Study (New Haven, 1910), 142-53; Sears, Chancellorsville, 120-24; James P. Skiff, Diary, April 14-16, April 23, courtesy of Scott N. Hilts, Arcade, NY; H. Smith, Diary, April 15; J. A. Smith, Diary, April 15-16; Welch, Diary, April 15.

- Alexander Bird, Diary, April 15-27, courtesy of Janet Bird Whitehurst, Los Banos, CA.; Welch, Diary, April 17, 18, 26; Ogden, Diary, April 24.

- Emory Sweetland to Mary Sweetland, April 16, courtesy of Lyle Sweetland, South Dayton, NY; “From the Army,” Cattaraugus Freeman, June 25; James D. Quilliam to Rhoda Quilliam, May 17, courtesy of Edithe Nasca, Fredonia, NY; H. Smith, Diary, April 28.

- J. A. Smith, Diary, April 23; Welch, Diary, April 23; Bird, Diary, April 26; Samuel DeForest Woodford to Mary Woodford, April 23, The Center for Western Studies, Augustana College, Sioux Falls, SD; Franklin Ellis, ed., History of Cattaraugus County, N.Y. (Philadelphia, 1879), 110.

- Newell Burch, Diary, April 27, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul; Ogden, Diary, April 27; H. Smith, Diary, April 27.

- Bird, Diary, April 27; H. Smith, Diary, April 28; J. A. Smith, Diary, April 28; Sears, Chancellorsville, 131-32, 136-51; Bigelow, Chancellorsville, 183-87; Ernest B. Furgurson, Chancellorsville 1863: The Souls of the Brave (New York, 1992), 67, 89-92.

- Burch, Diary, April 28; Dunkelman and Winey, The Hardtack Regiment, 51-52; Ogden, Diary, April 28; H. Smith, Diary, April 28; J. A. Smith, Diary, April 28; Warner, Diary, April 28; Official Report of Lt. Col. Henry C. Loomis, May 20, 1863, Regimental Letter Book, Ellicottville (NY) Historical Society (hereafter: Loomis, Official Report); Janesville (WI) Daily Gazette, May 6, 1, reprinting correspondence of the New York Tribune; Samuel DeForest Woodford to Mary Woodford, May [date illegible].

- Warner, Diary, April 28.

- Welch, Diary, April 29; Warner, Diary, April 29; Furgurson, Chancellorsville 1863, 91-95.

- Warner, Diary, April 29; Welch, Diary, April 30; Bird, Diary, April 29; J. A. Smith, Diary, April 29; Richard J. McCadden to his mother, May 10, courtesy of Ron Meininger, Gaithersburg, MD; James D. Quilliam to Rhoda Quilliam, May 17; Samuel DeForest Woodford to Mary Woodford, May [date illegible].

- Bird diary, April 30; Bryant, Diary, April 30; Burch, Diary, April 30; H. Smith, Diary, April 30; J. A. Smith, Diary, April 30; Warner, Diary, April 30; Timothy Glines to unknown recipient, May 9, published in the Potter Journal (Coudersport, PA), May 27; James G. Macomber to his mother, May 12, Electus W. Jones Papers, Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library, Duke University, Durham, NC; Sears, Chancellorsville, 192; Muster Rolls, 154th New York, April 30, 1863, National Archives, Washington, D.C.; E. D. Northrup, “Historical Sketch,” in William Fox, ed., New York at Gettysburg (Albany, 1900), vol. 3, 1055.

- Dunkelman and Winey, The Hardtack Regiment, 53; Burch, Diary, May 1; Skiff, Diary, May 1; H. Smith, Diary, May 1; Warner, Diary, May 1.

- Dunkelman and Winey, The Hardtack Regiment, 53; Bigelow, The Campaign of Chancellorsville, 262-65; Sears, 230-35.

- Warner, Diary, May 2; Welch, Diary, May 2; H. Smith, Diary, May 2; Noel G. Harrison, Chancellorsville Battlefield Sites (Lynchburg, 1990), 83-86; Bigelow, The Campaign of Chancellorsville, 279-85; Hamlin, The Battle of Chancellorsville, 48-54.

- Bigelow, The Campaign of Chancellorsville, 285-86, Map 18; Oliver Otis Howard, Autobiography of Oliver Otis Howard (New York, 1907), vol. 1, 363-65.

- Welch, Diary, May 2; J. A. Smith, Diary, May 2; Bigelow, The Campaign of Chancellorsville, 291-93, 295-99, 300-302; Hamlin, The Battle of Chancellorsville, 16, 64-68; Howard, Autobiography, 370-72.

- Bigelow, The Campaign of Chancellorsville, 300-301, Map 19; Hamlin, The Battle of Chancellorsville, 69-73; George W. Newcomb to his wife, May 9, USAMHI.

- Loomis, Official Report; Hamlin, The Battle of Chancellorsville, 74-76.

- Mark H. Dunkelman, “Main Address,” in Dedication of the Chancellorsville Monument to the 154th New York Volunteer Infantry, May 26, 1996 (154th New York Monument Fund, 1996), 14.

- “The Battle of Chancellorsville—Death of Adj’t S. C. Noyes, Jr.,” Cattaraugus Freeman, May 28; Thomas R. Aldrich to his mother, June 22, courtesy of Patricia Wilcox, Fairport, NY.

- James D. Emmons to his sister, May 12, courtesy of Leslie R. Page, Auburn, NY; Francis Strickland to his family, May 10, in Chuck and Peggy Strickland, The Road to Red House (N.p., 2007), 79-84; H. Smith, Diary, May 2; John N. Porter to Brother Thorpe, May 9, courtesy of Francis N. T. Diller, Erie, PA; Timothy Glines to unknown recipient, May 9, published in the Potter Journal, May 27; “The Battle of Chancellorsville—Death of Adj’t S. C. Noyes, Jr.,” Cattaraugus Freeman May 28; Charles H. Field to Adrian Fay, June 8, courtesy of Phil Palen, Gowanda, NY; Samuel R. Williams to Martha James, May 9, courtesy of Jack Finch, Freedom, NY.

- Warner, Diary, May 2; Aldrich to his mother, May 6; Oscar M. Taylor to Cousin Betthiah, May 9, courtesy of Virginia Canella, St. Petersburg, FL; William Charles to Ann Charles, May 12, courtesy of Jack Finch, Freedom, NY; Timothy Glines to unknown recipient, May 9, published in the Potter Journal, May 27; Hiram Vincent to Wealthy Vincent, May 8, courtesy of Robert Vincent, Alpharetta, GA.

- Burch, Diary, May 2; Loomis, Official Report; “The Battle of Chancellorsville—Death of Adj’t S. C. Noyes, Jr.,” Cattaraugus Freeman May 28; James W. Washburn to his parents, May 12, Washburn Pension File, National Archives.

- Loomis, Official Report; Ellis, History of Cattaraugus County, New York, 111; Bird, Diary, May 3; Alexander Bird, “My First Experience Under Fire,” Ellicottville (NY) News, January 20, 1894; Marcellus Warner Darling, Events and Comments of My Life (N.p., n.d.), 12-13; Richard J. McCadden to his mother, May 8 and10, courtesy of Ron Meininger; George A. Taylor to Eleanor Taylor, May 20, Chautauqua County Historical Society, Westfield, NY.

- Charles W. McKay, “’Three Years or During the War,’ With the Crescent and Star,” in The National Tribune Scrap Book (N.p., n.d.), 128.

- Warner, Diary, May 4 and 5; Bird, Diary, May 5; H. Smith, Diary, May 5; Sears, Chancellorsville, 389.

- Warner, Diary, May 6 and 7; Burch, Diary, May 7; Henry Van Aernam to Amy Melissa Van Aernam, May 7, USAMHI.

- J. A. Smith, Diary, May 7; Homer A. Ames to Susan Griswold, May 12, Fenton History Center, Jamestown, NY; Stephen R. Green to unknown recipient, undated, courtesy of Phil Palen, Gowanda, NY; Francis Strickland to Katy Strickland, May 12, in The Road to Red House, 85; Hiram Vincent to Wealthy Vincent, May 10.

- Muster Rolls, 154th New York, April 30, 1863; List of casualties accompanying Loomis, Official Report; “Losses in the 154th Regiment,” Cattaraugus Freeman, May 21; “Casualties of the 154th Regiment, N.Y.V., in the Engagement at Chancellorsville, May 2, 1863,” New York Daily Tribune, May 22; “Other Casualties,” New York Times, May 9; Sears, Chancellorsville, 475-91; Amos Humiston to Philinda Humiston, May 9, author’s collection; J. A. Smith, Diary, May 31; George Eugene Graves to Celia Smith, May 14, author’s collection; Warner, Diary, May 31; James D. Quilliam to Rhoda Quilliam, May 31; Samuel DeForest Woodford to Mary Woodford, May 31.

- Bryant, Diary, May 3; “Death of a Soldier,” Cattaraugus Freeman, June 25; Sweetland to Mary Sweetland, May 15 and19; William F. Chittenden to Mary Jane Chittenden, May 16, author’s collection; Samuel DeForest Woodford to Mary Woodford, May 15 and 16.

- Bryant, Diary, May 4-September 26; Welch, Diary, May 4-September 29; “From Washington,” Cattaraugus Freeman, June 4; Skiff, Diary, May 3-23; James W. Clements to his wife, May 17 and 24, courtesy of Judith Wachholz, River Falls, WI.

- Theodore Ayrault Dodge, The Campaign of Chancellorsville (Boston, 1881), 94-95, 103; Joel M. Bouton to Stephen E. Hoyt, May 18, courtesy of Maureen Koehl, South Salem, NY; John N. Porter to Brother Thorpe, May 9; McKay, “’Three Years or During the War,’ With the Crescent and Star,” 128 (quoting Philadelphia Inquirer); Report of Brig. Gen. Adolph von Steinwehr, May 8, 1863, in The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 128 vols. (Washington, DC, 1880-1901), Series 1, vol. 25, pt. 1, 645-46; Oliver Otis Howard to Elizabeth Waite Howard, May 9, Oliver Otis Howard Papers, Bowdoin College Library, Brunswick, ME; Oliver O. Howard, “The Eleventh Corps at Chancellorsville,” in Robert U. Johnson and Clarence C. Buel, eds., Battles and Leaders of the Civil War (New York, 1956), vol. 3, 199-201; Samuel P. Bates, “Hooker’s Comments on Chancellorsville,” in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, vol. 3, 219, 221.

- Dunkelman and Winey, The Hardtack Regiment, 61; Sears, Chancellorsville, 487; “A Letter From Capt. C. P. Vedder,” Cattaraugus Freeman, June 25; William Charles to Ann Charles, May 11; Timothy Glines to unknown recipient, May 9, published in the Potter Journal, May 27; George W. Newcomb to his wife, May 9; Isaac N. Porter to Charles Murray Harrington, May 13, The Courier (March/April 1991), vol. 7, issue 2, 24-25; Henry Van Aernam to Amy Melissa Van Aernam, May 15.

- William Charles to Ann Charles, May 17; Undated letter of Allen L. Robbins in undated clipping from Gowanda Reporter, Cattaraugus County Historical Museum, Little Valley, NY; Dwight Moore to his mother, May 8, Moore Pension File, National Archives; Note by James W. Bird in Richard J. McCadden’s copy of Hamlin’s The Battle of Chancellorsville, 128, courtesy of Jennifer McCadden, Lakeside, OR; “Army Correspondence,” quoting letter of James M. Mathewson, June 12, in undated clipping from Gowanda Reporter; George Eugene Graves to Celia Smith, May 14, author’s collection.

- Note by Mrs. Jay Quackenbush accompanying letter of Andrew M. Keller to Nancy Wheeler Brown, May 24, Cattaraugus County Historical Museum; John F. Wellman, “A Story of the 154 Regt. N.Y. Vols.,” Kansas State Historical Society, Topeka; Newton A. Chaffee, Decoration Day Address at Versailles, NY, 1896, Gowanda (NY) Area Historical Society; Thomas Avery Lee, “Alfred Washburn Benson, LL.D.,” in Kansas Historical Collections, vol. 14 (1918), 8-9; William D. Harper, Memoir, courtesy of Raymond Harper, Dunkirk, NY; Alexander Bird, “In the Southland,” Ellicottville (NY) Post, September 2, 1908; William Adams, ed., Historical Gazetteer and Biographical Memorial of Cattaraugus County, New York (Syracuse, 1893), 1019.

- Loomis, Official Report; “Losses in the 154th Regiment,” Cattaraugus Freeman, May 21, quoting letter of Alanson Crosby, May 13; Henry Van Aernam to Amy Melissa Van Aernam, May 15; Warner, Diary, May 2; James W. Washburn to his parents, May 12; Aldrich to his mother, May 6. Other sources using the “fought like tigers” simile include “A Letter From Capt. C. P. Vedder,” Cattaraugus Freeman, June 25; Timothy Glines to unknown recipient, May 9, published in the Potter Journal, May 27; George J. Mason to his sister Martha, undated, courtesy of Juliet Mason, Russell, PA; Isaac N. Porter to Charles Murray Harrington, May 13; John N. Porter to Brother Thorpe, May 9; Thaddeus L. Reynolds to his friends at home, May 20, Reynolds Pension File, National Archives; H. Smith, Diary, May 2; Francis Strickland to his family, May 10 and 21, in The Road to Red House, 82, 91-92.

- Dedication of the Chancellorsville Monument to the 154th New York Volunteer Infantry, May 26, 1996, passim; “Descendants Dedicate Memorial To 154th N.Y. At Chancellorsville,” The Civil War News (September 1996), 24. The other regimental monuments at Chancellorsville are to the 27th Indiana and the 114th Pennsylvania.

Related Battles

17,304

13,460