Cold Harbor Morning

By Daniel T. Davis

General Robert E. Lee was apprehensive. For the last three days, his Army of Northern Virginia held a line which stretched from the vicinity of Atlee’s Station on the Virginia Central Railroad southeast to the Mechanicsville Turnpike. Lee had clashed with Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, Maj. Gen. George Meade and the Army of the Potomac along Totopotomoy Creek and at Bethesda Church in mostly inconclusive fighting. Now, on the afternoon of May 31st, 1864, disturbing news reached his headquarters.

The day before, Union cavalry led by Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan had moved south from Old Church and engaged their Confederate counterparts under Brig. Gens. Matthew C. Butler and Martin Gary. This operation drew Lee’s attention as Sheridan drove the gray troopers back to a dusty crossroads, Old Cold Harbor. This lonely junction beyond Lee’s right flank was vitally important. One of its roads led directly to the Confederate capital at Richmond. The Virginian directed his nephew, Brig. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee, and his cavalry division to relieve Butler and Gary, along with elements from the recently arrived division from the Bermuda Hundred defenses under Brig. Gen. Robert Hoke.

Sheridan resumed his offensive earlier in the day. Hearing this alarming development, Lee dispatched Maj. Gen. Richard Anderson’s First Corps to reinforce Hoke. But for the time being, Hoke was on his own. In an “obstinate fight” Brig. Gen. Alfred Torbert’s Union division captured Cold Harbor and the Confederates assumed a new line a short distance to the west. Apprised of the situation, Anderson planned to move against Sheridan on the morning of June 1.

Curiously, Sheridan had abandoned Cold Harbor that evening. “My isolated position…made me a little uneasy,” he wrote. “I felt convinced that the enemy would attempt to regain this place.” George Meade was not happy when he was informed of Sheridan’s decision. The Union high command had also come to appreciate the value of the crossroads. Another artery which passed through the intersection ran to the Federal supply base at White House Landing. Meade implored Sheridan to hold “at every hazard.” Maj. Gen. Horatio Wright’s VI Corps and Maj. Gen. William “Baldy” Smith’s XVIII Corps also received orders to march to Sheridan’s aid.

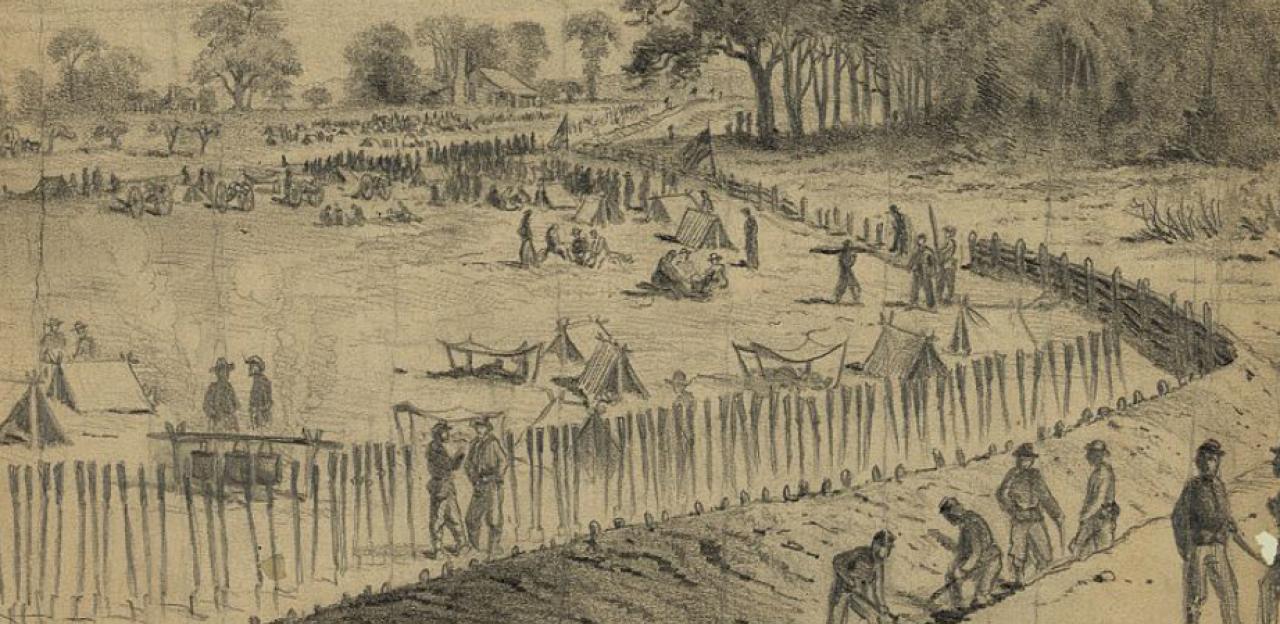

When he received Meade’s directive, Sheridan turned Torbert’s horsemen around and quietly returned to their original position. Colonel Thomas Devin’s brigade held Cold Harbor. To Devin’s right front was Brig. Gen. George Custer’s Michigan Brigade. On Custer’s right and extending past Beulah Church, Brig. Gen. Wesley Merrit commanded the Reserve Brigade. “The breastworks which the enemy had thrown up were brought into service” wrote Maj. James Kidd of the 6th Michigan Cavalry in Custer’s command. “Ammunition boxes were distributed on the ground by the side of the men so they could load and fire with great rapidity. This was a strong line in single rank deployed thick along the barricade of rails. Behind the line only a few yards away were twelve pieces of artillery.” Anxiously, the blue troopers waited for daylight.

“At 5 a.m., as things remained quiet in front, coffee was prepared and served to the men as they stood to horse,” recalled Capt. Theophilus Rodenbaugh, the commander of the 2nd U.S. Cavalry in Merritt’s brigade. “My fourth cup of coffee was in hand when a few shots were heard in front, causing a general pricking up of ears.” The skirmish fire was kept up until about 8 a.m. when the Confederate advance was spotted.

Leading Anderson’s corps was the division of Maj. Gen. Joseph Kershaw. At its head was Kershaw’s former brigade of South Carolinians, led by Col. Lawrence Keitt, recently arrived from duty in the Deep South. “The men began to snuff the scent of battle,” wrote one Keitt’s soldiers. “Cartridge boxes were examined, guns unslung, and bayonets fixed while the ranks were being rapidly closed up. After some delay and confusion, a line of battle was formed along an old roadway.”

The South Carolinians entered an open field and moved toward a belt of timber. Keitt remained mounted on his gray “like a knight of old”. As they entered the woods, a rebel yell rent forth from the ranks which was greeted by a volley from the Federals. “A sheet of flame came from the cavalry line, and for three or four minutes the dine was deafening,” Rodenbaugh remembered. “The repeating carbines raked the flank of the hostile column while the Sharps single-loaders kept up a steady rattle.”

“So furious was the fire that the Confederate infantry did not dare to come out of the woods…the fire from the Spencers from behind the rails keeping them back” Kidd recalled. At some point during the attack, Keitt was shot dead from his horse. Union horse artillery also lent their weight to the fight. A member of the 1st New York Dragoons in the Reserve Brigade recalled that fire from Lt. Edward Williston’s Battery D, 2nd U.S. set the woods on fire “and the shrieks of the rebel wounded were first heightened, then stifled, by the flames.” Kershaw recoiled in the face of Sheridan’s front. Rather then bring up the rest of his division and risk another assault, he pulled back and formed his men in line to the left of Hoke. Sheridan’s troopers had done their job and around 10 a.m. the head of the VI Corps tramped in to relieve the tired cavalrymen. Soon, it would be the Federals’ turn to launch an infantry assault at Cold Harbor.

Related Battles

950

1,000