Though many clergymen from the slave states sought to avoid political themes in their sermons during the secession crisis, the overwhelming majority came to support the creation of the Confederate States of America during the winter and spring of 1861. As the Southern Baptist Convention put it in May 1861, “we most cordially approve of the formation of the government of the Confederate States of America.” Later in the year, the Tennessee Methodist Conference approved a resolution supporting the Confederacy and called for the appointment of “as many preachers of this conference as … proper to the chaplaincy of our army.”

Putting chaplains into service, however, proved more difficult than the Tennessee Conference had imagined. The original legislation authorizing a War Department for the new Confederacy passed in February 1861. It did not, however, include provisions for army chaplains. Women, who had played a leading role in Christianizing the southern states in the decades before the war, along with local elected officials from across the South petitioned the Confederate Congress to create the structures to support chaplains for the army. Francis S. Bartow of Georgia introduced the necessary legislation in May 1861, and the bill quickly became law.

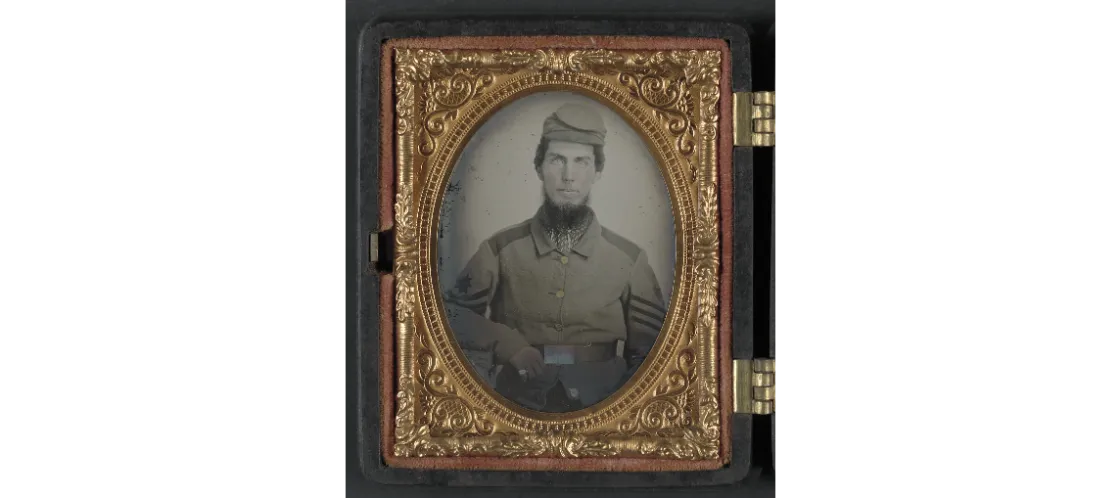

The law provided the president with the authority to appoint “chaplains to as many regiments, brigades, and posts as he ‘deemed expedient.’” The pay was low and there was no guidance concerning age, health, education, or “ecclesiastical status.” No duties were listed, no uniform described, no rank insignia designated, nor training stipulated. Ordination was not required, thus ministers, priests, laymen, or an especially religious soldier in the ranks qualified for appointment. The identification of a candidate depended on the regimental commander’s written recommendation which was sent to the War Department for approval.

As the armies grew, the number of chaplains failed to keep pace. Over the entire course of the war, this lack of structure for chaplains remained a problem for the Confederate armies and no more than half of all the regiments included chaplains on their rolls. Denominational leaders, who saw the army as a ripe field for missionary work, recognized the problem and beginning in 1862, sent missionaries to the army and increased the amount of religious literature circulated in the camps.

In the Army of Northern Virginia, this work was helped along by the chaplains of the 2nd Corps who organized a Chaplain’s Association that met regularly for preaching and prayer. Though these meetings encouraged cooperation between chaplains, denominational allegiances remained strong.

Chaplains also preached to and served multiple regiments. Together, the missionaries, colporteurs who circulated religious literature, and chaplains created a network of preaching, reading, and prayer meetings that led to significant revivals in the major Confederate armies that began in late 1862 and continued with varying intensity through the war’s last days. In the decades after Confederate surrender, the men who preached in the camps and hospitals continued to lead the South’s white denominations. They led churches, taught in seminaries, and edited denominational newspapers and in so doing influenced a new generation of white southern church members and leaders.

Further Reading:

- The Spirit Divided: Memoirs of Civil War Chaplains, The Confederacy By: John Wesley Brinsfield, Jr., ed.

- Apostle of the Lost Cause: J. William Jones, Baptists, and the Development of Confederate Memory By: Christopher C. Moore.