The Dunkers

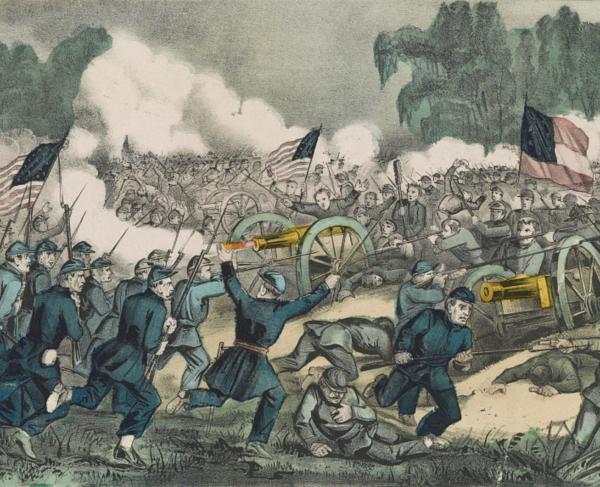

People of peace caught in the bloodiest day in American history – that was the situation confronted by the congregation of the Dunker Church on September 17, 1862. Located on a strategic plateau that became a Confederate artillery position in the battle of Antietam, and the target of the Union advance, the Dunker Church served as a place of worship for the pacifist Christian sect known as the Dunkers since its construction in 1852.

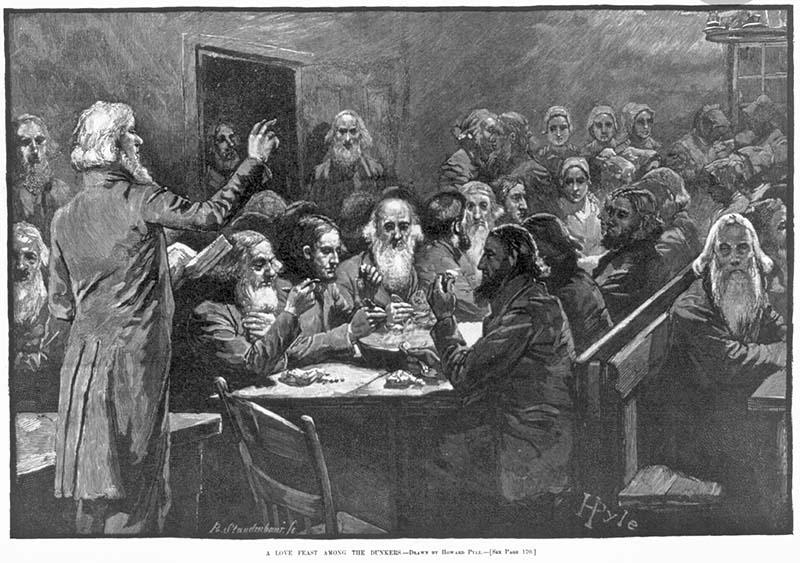

Established in Germany in 1708, the Dunkers were members of the German Baptist Brethren who adhered to a literal interpretation of the New Testament. Though similar to other sects like the Quakers, Amish, and Mennonites in their beliefs, the Dunkers distinguished themselves by their method of baptism, through which they also garnered their name. While other religious groups practiced infant baptism in a church or home by sprinkling water on the baby, the Dunkers practiced a river baptism in which an adult fully submerged, or dunked, themselves in the water three times in the name of the Holy Trinity. The Dunkers also opposed drinking alcohol, gambling, or any sort of indulgence and were known for their humble appearance.

During services, members of a congregation entered the church and divided, with men seating on one side and women on the other. The pastor stood in front of the congregation at a small table with the Bible while he delivered a sermon. This was followed by the singing of several hymns, with no musical or instrumental accompaniment. Dunker services were typically about three to four hours long, as religion was the central element of a Dunker’s life. A Dunker church likewise reflected this degree of humility, adorned not with stained glass or steeples but by simple white walls and square windows. (These prominent white walls became a recognizable and easily seen landmark amidst the smoke and chaos of the battle in 1862.) Instead of rented pews, which signified status within the community, churchgoers chose to sit on common benches.

The Dunkers typically settled in rural communities throughout Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia and were also known as “Dunkards,” “Tunkers,” and Täufer in German. Though they lived peacefully among other religious groups, they desired a degree of separation from mainstream society, and certainly did not worship with other sects or denominations. By 1861 the Dunkers, like most pacifist groups, worried about the war’s impact on their religious practices but ardently supported the anti-slavery movement. However, much like the rest of the nation, Dunker congregations were often divided by the war or found themselves at odds with their respective governments. Though some Dunkers served in the military on both sides of the conflict, these men were typically the sons of congregation members and had not yet been baptized as formal members of the church.

John Kline, a Dunker elder, and pastor from the Shenandoah Valley, vehemently opposed secession and the treatment of pacifists by Confederate draft laws. Therefore, he fought the Confederate government for the exemption of the German Dunkers. For his protest, as well as for allegedly preaching on both sides of the Mason-Dixon line, Kline was murdered by Confederate vigilantes in 1864. In the Shenandoah Valley, though, the Southern Dunkers found an ally in Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, a fellow Valley native and general in the Confederate army. Having known many Dunkers before the war, Jackson took note of their religious scruples and assigned the pacifists under his command to teamster duty, allowing them to obey Confederate law without actively committing violence.

Northern Dunkers likewise opposed the Federal draft and generally succeeded in avoiding it. For its anti-slavery roots, the Union cause became attractive to many Dunkers who sought a realization of the New Testament, particularly unity and fellowship among all men. However, some Northern congregations thought this to be at odds with their pacifist ideals, much like those in the South. Similar to John Kline, Northern elders petitioned the state and Federal governments for exemption from the draft. The Marsh Creek Dunker congregation, just several miles outside of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, experienced this conflict firsthand. Though the Pennsylvania Constitution granted pacifist sects exemption from military service, the Dunkers’ lack of membership records made it difficult to prove affiliation with the Dunker faith. Thus, two impending Confederate invasions of the North were successful in drafting at least several able-bodied men of the Marsh Creek congregation into Union ranks. Indeed, the war itself showed up on the Dunkers’ doorstep when the armies met at Gettysburg in July 1863. Joseph Sherfy, a minister and elder of the Marsh Creek church, returned to his farm just south of Gettysburg to find it ravaged by war. His peach orchard, now famous, served as an artillery position and objective for both armies.

Much as the Marsh Creek community experienced the war firsthand in 1863, the Antietam Dunkers doubtlessly did ten months earlier. On Sunday, September 14, 1862, churchgoers could see smoke and hear cannon fire in the Battle of South Mountain to the east. Two days later, Confederate infantry and artillery arrived in force around the church. With the armies approaching, many of the church’s members fled. When they returned, they found their church riddled by bullets and shell fragments, dead men and horses piled across the road, and the debris of war scattered about. Samuel Mumma, one of the church founders, returned to find his farm burned to ashes. After the battle, Alexander Gardner forever etched the Dunker Church into the American conscience with his haunting photographs of Confederate casualties in front of the church – and the Dunkers were forever remembered as a people of peace ravaged by war.

Further Reading:

- Too Afraid to Cry: Maryland Civilians in the Antietam Campaign By: Kathleen A. Ernst.

- To Antietam Creek: The Maryland Campaign of 1862 By: D. Scott Hartwig.

Related Battles

12,401

10,316