Death & Burial: Guideposts to Gettysburg's Dead

Images of Civil War soldiers are one of the greatest humanizing documents in history. With the development and spread of mass-market photographic techniques, posed portraits of average soldiers — not just wealthy officers — show us the face of war. They had the same concerns as we do today, and loved ones wishing fervently for their safety. In-field documentary photography provided unprecedented evidence of what life in the field was like, and graphic images of the aftermath of battle introduced the world to the harsh and bloody reality of war.

Macabre photos of battlefield dead can and should do much more than illustrate the horrors of combat. To look at the bloated, inhuman forms is to intrinsically know that, just days earlier, the bearers of those grim visages charged toward their fate full of life. Their still forms, captured on glass plates for posterity, elicit pity and prompt obvious, sympathetic questions: Who were they? Were they identified and returned home? What became of their families?

And yet, these images offer far more than emotional resonance. Just as big battles are not isolated clashes between warring armies, but are part of a broader continuum of events, these photos are powerful primary source documents that can teach us much within the broader context of the evidence left behind by soldiers and civilians. Combat physically scarred the terrain and left indelible impressions upon those who witnessed it. These personal experiences were recounted in official and unofficial accounts of the battle, and captured in newspaper reporting. Detailed diaries of soldiers, civilians and, later, relief workers, record minute particulars of the fighting and its aftermath.

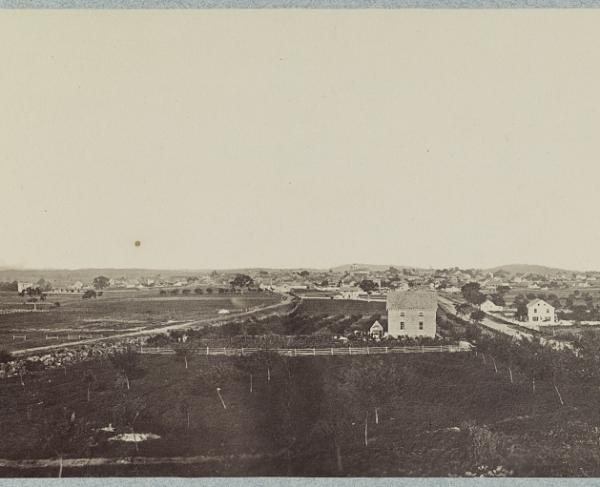

Photographers came, too, and left behind a body of work that gives a glimpse of 1863 Gettysburg available nowhere else. And when human remains were exhumed from battlefield graves and moved to proper cemeteries — near and far, small or large — in the weeks, months and years after the battle, those doing the work created a whole new series of records with detailed maps. Thus, thousands of accounts of the battle and its aftermath intersect with photographs, sketches, maps and the battlefield itself to bring to light the deadly scenes of warfare. These physical and figurative guideposts can help us understand not only how the battle unfolded, but also the stories of individual soldiers who fought there.

Of course, to a certain extent, the same is true of any battlefield. But a host of factors — its incredible loss of life, physical location close to eastern population centers, early preservation efforts, prestigious cemetery dedication and more — have rendered Gettysburg the most famous and well-documented of all Civil War actions. Veterans and historians have made great use of this remarkable body of evidence for 152 years and counting, providing insights that can be applied to other battles. The process of combat, death, burial and aftermath that occurred at Gettysburg was mirrored in other communities.

Even with these unparalleled resources, limits to potential discoveries remain. Consider the information both contained in, and lacking from, a typical postwar letter — this one from New Jersey artillery lieutenant Augustine Parsons — describing the action on July 3, 1863:

“…a shell from the enemy’s battery burst in front and slightly above us. A small piece struck my horse, but did no harm. A small piece struck an old German soldier, who was number two at the gun. He wheeled around on one foot and fell flat on his back. I jumped from my horse, bent down by him, called him by name. The only audible reply was, ‘water.’ I called for a canteen, placed it to his lips. He took one swallow and was dead.”

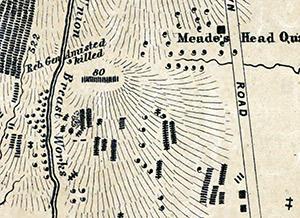

The account continues and also details the death of another man. We know that Parsons was at Gettysburg commanding Battery A, 1st New Jersey Artillery, and in his July 17, 1863, official report he has the battery coming up “about one-fourth of a mile south of the Gettysburg Cemetery,” south of the famous Copse of Trees in support of the Union repulse of Pickett’s Charge. A look at the excellent 1876 battle action maps by historian John Bachelder confirms this, as, more recently, do James Hessler and Wayne Motts.

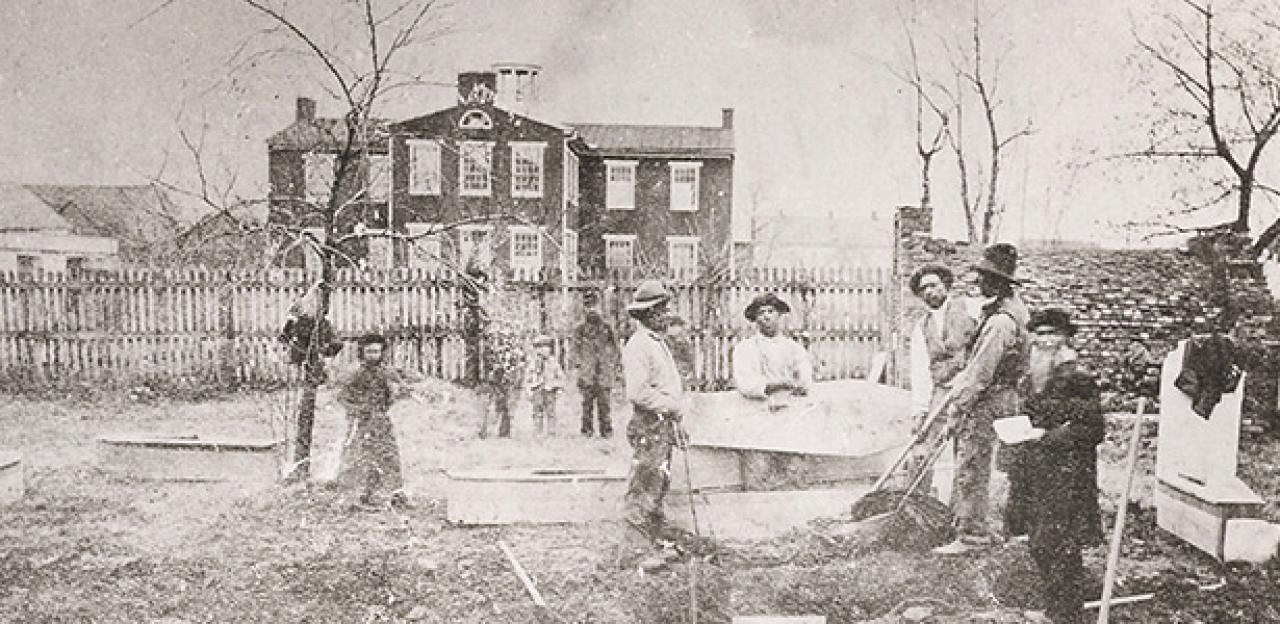

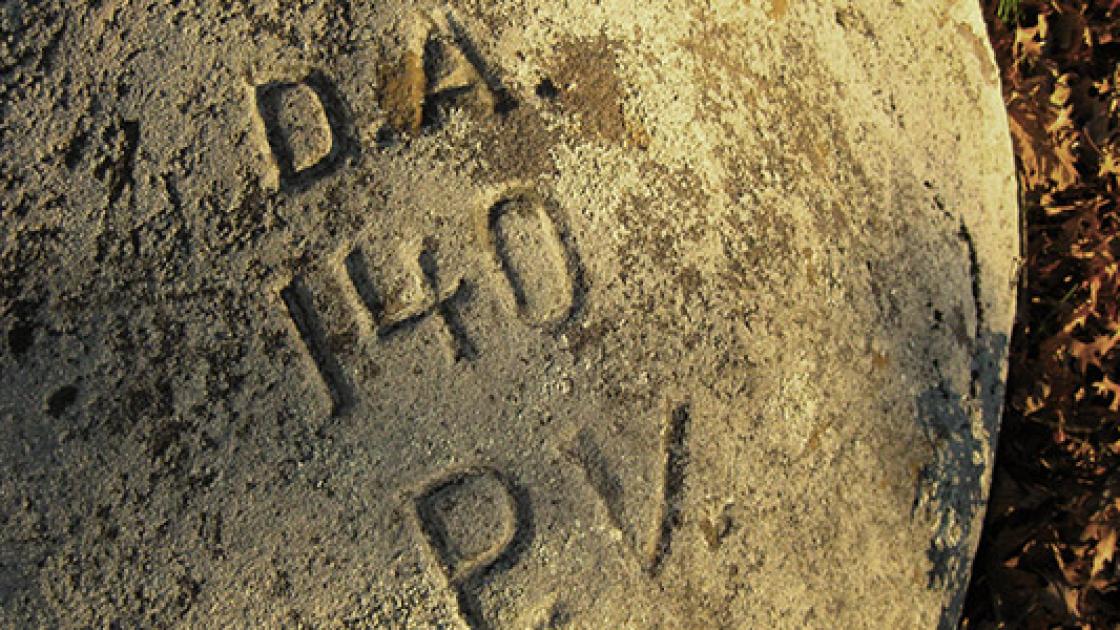

Parsons reported two men killed at Gettysburg, and these are known to be privates Ludwig Kreisel and George Kutter. One of these two is the man who died while taking his last drink of water, but which? And what became of that soldier afterward? According to early burial records in possession of the Gettysburg National Military Park, both were buried near Peter Frey’s stone house. The 1864 “Elliot Map,” which aimed to be a careful study of Gettysburg burial places, indicates 10 Union soldiers buried just northwest of the Peter Frey’s house. By 1864, Kreisel and Kutter had been reinterred right next to each other in the Soldiers National Cemetery. Perhaps someone might do more research to determine where the men were from, or even figure out their respective ages in hopes of seeing whether one better fits Parson’s “Old German” description, but for now, knowing where they fought, roughly where they were buried and where they now rest is the best we can do. This is what we can do for one man. One down, roughly 10,000 to go.

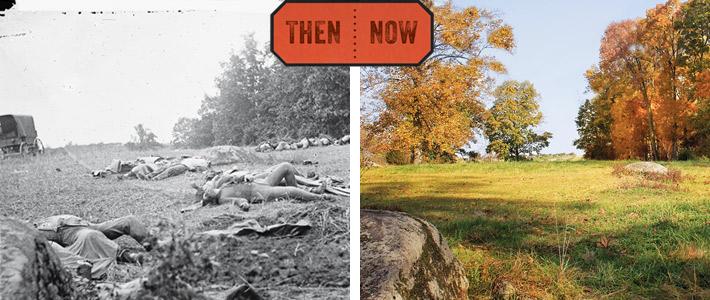

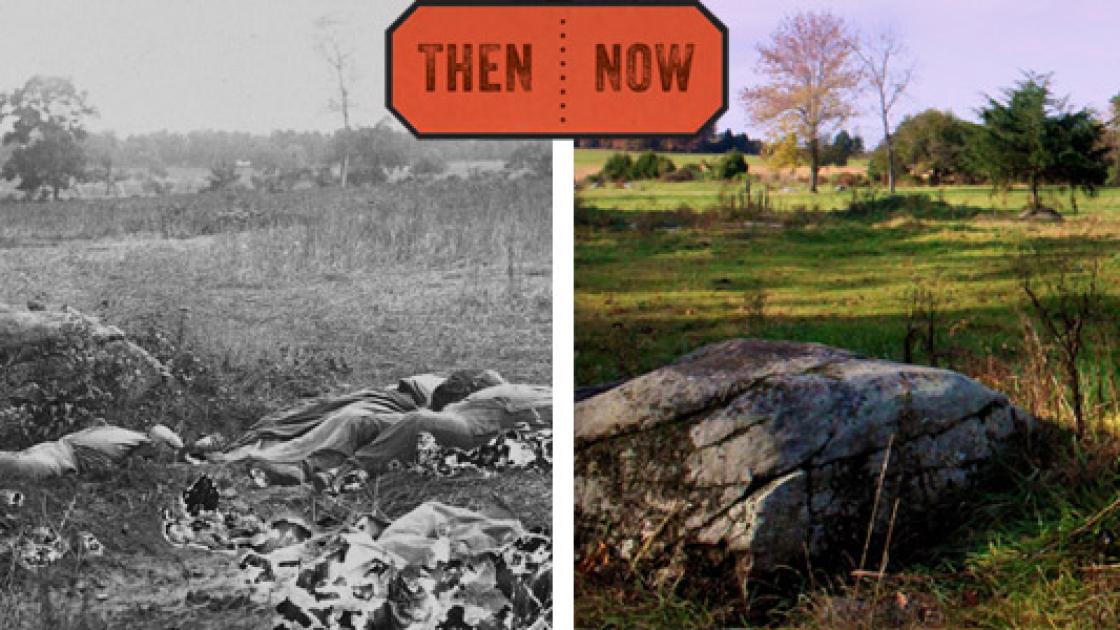

In areas where post-battle photographs were taken, however, we can often establish more pinpoint accuracy. These images are likely to show the dead in the area very close to where they died, connecting specific soldiers geographically to the places where they fell. But first, you need to establish exactly where the photograph was recorded, a process undertaken in the longtime work of photographic historian William A. Frassanito. His efforts demonstrate how, once one can divine when and where a photo was taken, the photos transform from interesting works of art to primary documents, more richly endowed with information than any other source. Based on location alone, the dead Confederate soldiers recorded by Alexander Gardner and his crew around Devil’s Den can be narrowed down to belonging to just a few different regiments. Using burial and hospital records (thousands of wounded soldiers ultimately died in Gettysburg-area army hospitals, firmly establishing they were not photographed in death on the field itself), we can, by process of elimination, further narrow down some of the dead to just a few names.

Gettysburg’s human toll is more visually documented than that of any other Civil War battlefield. Thirty-seven post-battle photographs show roughly 100 corpses — about 1 percent of the dead at Gettysburg. Of these, we can photographically pinpoint some 80 bodies, all of which are near Devil’s Den or on the Rose Farm.

Post-battle sketches can help divine a few more locations of death, but the most substantial, even if not the most precise, guideposts involve the combination of eyewitness accounts with the Elliot Map and the burial records left by those who exhumed remains from battlefield graves, mostly in 1863–1864 (Union) and 1871–1873 (Confederate). These sources have been expertly mined, consolidated, interpreted and assembled into rosters of the dead by an array of historians, especially Kathleen Georg Harrison, Robert K. Krick, John Busey and the late Gregory Coco.

The assembled rosters account for some 4,700 Confederate and 5,100 Union soldiers killed or mortally wounded at Gettysburg. Thousands of these listings include additional information — fascinating information like age, hometown, occupation, place of death and burial, process of exhumation and final resting place. For example:

- Pvt. William P. Miller, Co. B, 3rd South Carolina Battalion, killed July 2, 1863, buried George Rose’s farm, west of barn, under large cherry tree “grave deep, with board cover with 6 others,” now buried Magnolia Cemetery, Charleston, grave 24, since 5/10/1871

- Capt. Samuel Wiley Gray, Co. D, 57th North Carolina, 21 years old, killed July 2, 1863, to the right or south of Menchey’s Spring at the foot of East Cemetery Hill, possibly buried by a Capt. C.H. Hawkins, USA. Gray’s father, Robert, with the help of Dr. O’Neal, removed his son’s body Nov. 13–16, 1865 to Winston, N.C.

We can approximate their locations of death using official reports, battlefield accounts, maps, postwar photographs (which might, for instance, show the cherry tree mentioned as a landmark above) and the battlefield itself. For some of the dead, the Elliot Map will help narrow down their initial burial sites. Despite all the work done to date, however, lifetimes of research remains to better understand Gettysburg’s dead.

For example, all of this collected knowledge about the dead brings to light the fact that the remains of several hundred soldiers are unaccounted for, still reposing in their battlefield graves. This is known to be the case at other battlefields as well. It’s never too long before construction or archaeological work in Georgia, Virginia, Tennessee or elsewhere unearths a Civil War soldier’s bones and personal effects. This, along with our increasing understanding about the places soldiers died, demonstrates the critical role of battlefield preservation. Understanding how and where the dead were strewn, buried and reburied at a place like Gettysburg can help us picture and understand what it was like at the others.

Further Reading

For further reading on how archival research in photographs, maps, and other primary sources have helped illuminate the individual stories of men who fought and died at Gettysburg, consider the following sources:

- Download the Elliot Burial Map from the Library of Congress’s Civil War Maps Collection.

- For the latest analysis of losses on the third day, see James A. Hessler and Wayne Motts, Pickett's Charge at Gettysburg: A Guide to the Most Famous Attack in American History (2015).

- For aftermath, Union and Confederate hospitals and moments of death, see the work of Gregory A. Coco: A Vast Sea of Misery (1988), Wasted Valor (1990), Gettysburg’s Confederate Dead (2003), Killed in Action (1992) and A Strange and Blighted Land (1995).

- For a roster of Confederate dead, see Robert K. Krick’s Gettysburg Death Roster (1981).

- For Union mortalities and burials see two works by John W. Busey: These Honored Dead (1996) and The Last Full Measure (1988).

- For photographic analysis see the following books by William A. Frassanito: Gettysburg: A Journey in Time (1975), Early Photography at Gettysburg (1995), Gettysburg Then & Now (1996) and The Gettysburg Then & Now Companion (1997).