Don't Give Up the Ship

In the tumultuous years leading to the Revolution, merchants and sailors endured the initial brunt of Parliament’s new taxes and onerous regulations, and so it is not surprising that they were among the first to argue for American rights. It was natural that when protest turned to war, Americans looked to the sea to carry on their struggle for independence.

On July 3, 1775, George Washington took command of the American army at Cambridge, Massachusetts. A quick survey of the situation convinced him of the need for naval action. Meanwhile, at Machias, Maine, Jeremiah O’Brien had already led a group of Sons of Liberty to seize the Royal survey vessel Margaretta. Buoyed by such boldness, Washington quickly launched his own naval offensive.

The British in Boston depended entirely upon the sea for supply. On the morning of September 5, 1775, the schooner Hannah hoisted sail under the command of Nicholson Broughton and stood out from Beverly bound east toward Cape Anne to prowl for British prey. She was the first vessel to be commissioned in the Continental cause. Two days later she took her first prize, the British-controlled vessel Unity.

Hannah’s triumph led Washington to commission additional vessels. Caught unaware, the British scrambled to defend their supply lines, but in the meantime, Washington’s pesky squadron took 55 prizes.

Buoyed by Washington’s naval success, New England delegates, led by John Adams, in the Continental Congress pushed for the creation of an American fleet. Others in Congress, particularly southern delegates, thought the idea a cynical scheme by which New Englanders sought to enrich themselves. As a compromise, on July 18, 1775, Congress resolved that each colony should take responsibility to arm vessels to protect its ports. However, these “State Navy” efforts were too ineffectual to satisfy the more naval-minded Americans. Finally, Congress agreed to the formation of a Continental navy, and on Friday, October 13, 1775, they voted to dispatch two vessels to “cruise eastward.”

In November 1775, Congress created the Marine Corps and approved the first “Navy Regulations.” In December, Congress appointed Esek Hopkins commander in chief of the Continental Navy and appropriated money for the construction of 13 frigates. Seizing the initiative the following February, Hopkins led a Continental squadron to raid Nassau in the Bahamas.

Continental vessels did not confine their cruising to American waters. In November 1776, Reprisal, under the command of Lambert Wickes, entered Quiberon Bay carrying the newly appointed minister to France, Benjamin Franklin. After landing Franklin, Wickes cruised European waters, taking several enemy prizes. Other Continental captains also ventured across the Atlantic, none to more fame than John Paul Jones.

On September 23, 1779, Jones, in command of the converted French East Indiaman Duc de Duras, renamed Bonhomme Richard in honor of his friend Benjamin Franklin, encountered British merchant ships under the escort of HMS Serapis and Countess of Scarborough. In a fierce battle, Jones came alongside and grappled Serapis. In the midst of the carnage, Serapis’s captain Richard Pearson called over to ask if Jones intended to strike. The answer, as recorded in legend, came back “I have not yet begun to fight!” Jones gained the victory even though he lost his ship.

Jones, Wickes, Hopkins and other Continental captains launched America’s naval traditions, setting an example of skill, bravery and dedication that would serve as a hallmark across centuries. While the Continental Navy did not play a decisive role in the Revolution, sea power did; the French naval victory over a British fleet in the battle off the Virginia Capes on September 5, 1781, sealed the fate of General Charles Cornwallis’s surrounded army at Yorktown.

The Quasi-War

The American Republic was born into a hostile world. Great Britain sought revenge and the new nation’s first important ally, France, slipped into revolution and chaos. On the high seas American ships were harassed and attacked. Chief among the new enemies were the Barbary corsairs.

For generations, North African seafarers of the Barbary states had seized foreign merchantmen and held their crews for ransom. All those who wished to pass through the Mediterranean, American ships included, had the choice of either paying tribute or fighting. In response, Congress, prodded by President Washington, finally voted to build a federal navy to defend commerce, and on March 27, 1794, approved the construction of six frigates.

Less than a year after the six keels had been laid, word arrived that Algiers had signed a treaty allowing American ships to pass unmolested. On May 10, 1797, the first of the frigates, United States, slipped into the water at Philadelphia. In September, Constellation was launched at Baltimore, and in October, Constitution went down the ways at Boston. The three remaining hulls were left on the stocks, although work later continued and they were launched between 1799 and 1800.

In the Caribbean, French privateers often fell upon American vessels. Following a failed diplomatic mission to France, President John Adams set the nation on a course to defend its trade and honor by force. Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Stoddert dispatched a number of vessels south to protect American trade. Among them was Constellation, under the command of Captain Thomas Truxtun. On February 9, 1799 Constellation defeated the French frigate L’Insurgente near the island of Nevis. Almost a year later, Truxtun distinguished himself again when Constellation engaged and defeated another French frigate, La Vengeance, off Guadeloupe. Elsewhere, American naval forces captured more than 80 French ships with the loss of only one U.S. vessel. Such a succession of triumphs convinced the French of the futility of continuing the conflict and, on September 30, 1800, a convention was signed ending the war.

Barbary War

At the dawn of a new century, a new president, Thomas Jefferson (who preferred gunboats to frigates) was urging naval reduction when an old adversary again began to disrupt trade. The bashaw of Tripoli declared war on the United States on May 10, 1801, and Jefferson responded by sending naval forces consisting of Constitution and Philadelphia, along with four smaller vessels, to the Mediterranean. With the arrival of Commodore Edward Preble’s squadron in 1803, the Americans pressed the Tripolitans. With Philadelphia cruising off its coast, Preble declared the port of Tripoli in a state of blockade. On October 31, 1803, Philadelphia, under the command of William Bainbridge, entered the harbor in pursuit of a fleeing corsair. As his quarry scurried under the protection of shore batteries, Bainbridge came about towards open water but ran the ship hard aground. Forced to surrender his ship, Bainbridge and his crew were thrown into confinement.

In Tripolitan hands, Philadelphia posed a serious threat. At dusk on February 16, 1804, Lieutenant Stephen Decatur slipped into the harbor aboard the ketch Intrepid. Decatur and his men hid below while several crewmen, including an Italian pilot, stayed on deck disguised as Arab sailors. As the ketch pulled alongside the frigate, the pilot sought permission to tie up alongside the frigate. Foolishly, the Tripolitans passed a hawser down to Intrepid nd, in a moment, 50 American seamen were over Philadelphia’s gunwales. Within 15 minutes Decatur and his men had taken the ship, set her afire and escaped.

Preble tightened the blockade of Tripoli, launching a series of five attacks against the port, bringing his ships in close enough to deliver a series of devastating broadsides against shipping and the harbor’s defenses. Preble’s determined assaults weakened the Tripolitans. His successor, Samuel Barron, set in motion the final campaign, which involved an overland march from Egypt led by Marine Corps Lieutenant Presley O’Bannon and the American consul William Eaton. Threatened by land and sea, the bashaw decided to parley and a peace treaty was signed on June 4, 1805.

War of 1812

The practice of “impressment” — seizing sailors off merchant ships for military service — added to rising tension between the United States and Great Britain. At war with France, the Royal Navy needed men, and while few questioned the impressment of British subjects off British ships, extending that practice to U.S. vessels violated American sovereignty. Faced with British intransigence, the United States declared war on June 18, 1812. With a force of 10 frigates, two sloops, six brigs and a ragged assortment of schooners and gunboats, the United States Navy faced the world’s greatest sea power — the nearly 1,000 ships of the Royal Navy.

The tiny U.S. Navy acquitted itself well in the first months of the war, humiliating the British in a series of battles from August through December 1812 that sent Britannia reeling. Captain David Porter, commanding Essex, wreaked havoc on British trade. Sailing from New York, Essex cruised for two months between Bermuda and Newfoundland and in that time took nine prizes, including Alert, the first British warship to surrender to the Americans.

Isaac Hull in Constitution, having avoided capture at the onset of the war, slipped out of Boston early on August 2. On the afternoon of August 19, Constitution spotted and closed on the British frigate Guerriere. For more than two and a half hours Constitution and Guerriere slugged it out. The carnage was horrendous. In the midst of the battle, an American seaman is reported to have seen a British ball strike Constitution’s side and fall harmlessly into the water. Upon which he yelled, “Huzzah, her sides are made of iron!” earning the ship her perpetual sobriquet, “Old Ironsides.” At about 6:30 p.m., the British warship struck her colors.

On October 25, the frigate United States, commanded by Stephen Decatur, captured Macedonian, and on December 29, Constitution, now commanded by William Bainbridge, took Java off the coast of Brazil. David Porter, still commanding the frigate Essex, took the war around Cape Horn into the Pacific, where he virtually destroyed the British whaling fleet.

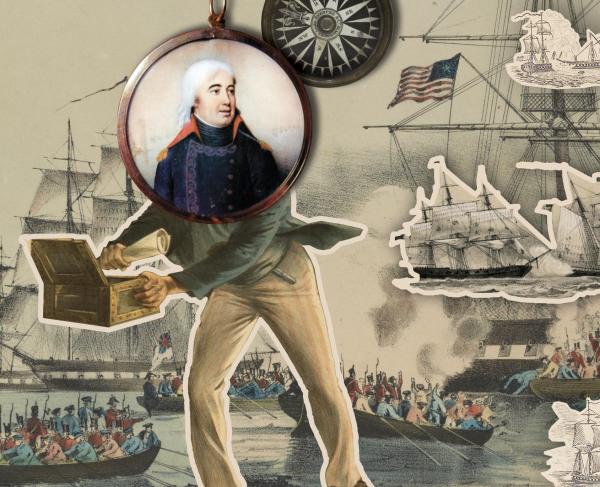

HMS Shannon blockaded Boston, but on June 1, 1813, the frigate Chesapeake, under the command of James Lawrence, left the port to challenge the situation. Just outside the harbor, at a distance of less than 150 feet, the two frigates exchanged furious broadsides, then Shannon sailed into a raking position and sent devastating fire along the full length of Chesapeake’s spar deck. Lawrence, mortally wounded, issued his last, futile command, “Don’t give up the ship!”

Lawrence’s heroism inspired his brother officers, including the American commander on Lake Erie, Oliver Hazard Perry. Having arrived at Erie, Pa., on March 27, 1813, Perry found a bustling yard with several vessels already under construction. Under his direction, work proceeded briskly, and by early August Perry had his fleet on the lake and ready for service. Opposing him was a British squadron under the command of Captain Robert Barclay. On the afternoon of September 9, the British sailed out onto the lake seeking battle.

Shortly after dawn, the two fleets came into sight of one another near Put in Bay. From the topmast of his flagship Lawrence, which he had named for his friend, the fallen hero, Perry flew a pennant emblazoned with the motto, “Don’t Give Up The Ship.” For more than two hours the battle raged. Lawrence took the brunt of the combat on the American side and, in the midst of the battle, Perry shifted his flag to Niagara. By three in the afternoon, Barclay realized his situation was hopeless. Perry later summarized the action: “We have met the enemy and they are ours.”

Lake Champlain, at the border between New York and Vermont, was a critical link in the strategic corridor of waterways running between Canada and the United States. In the summer of 1814, the British launched a major invasion along this route. The British General George Prevost ordered George Downie, the British naval commander, down the lake. Lieutenant Thomas Macdonough, the American commander on the lake, anticipated the British movement and placed his squadron into the confines of Plattsburg Bay. When British troops reached a point near Plattsburg, Prevost halted and insisted that Downie attack Macdonough.

On Sunday morning September 11, 1814, Macdonough received a signal from his lookout — “enemy in sight.” Macdonough was in a strong position; the British squadron would have to tack north into the wind to come alongside him. As a result, only a few of their cannon could be brought to bear on the Americans, while Macdonough, having rigged spring lines, could turn his ships and use all his guns to rake the advancing enemy. By noon the battle was over, and the entire British squadron was in American hands. Prevost wasted little time in retreating his infantry back to Canada.

A treaty of peace ending the war was signed Christmas Eve in Ghent, Belgium. However, since news took time to travel, hostilities continued into the New Year, including a failed British attempt to capture New Orleans. On February 20, 1815, Constitution, under the command of Charles Stewart off the Madeira Islands, displayed extraordinary speed, maneuverability and skill in her final engagement of the war, swiftly and soundly defeating two British ships.

The Second Barbary War

Early in 1815, the dey of Algiers once more let loose his corsairs to molest American ships. The war with Britain now concluded, President James Madison had at his disposal enough vessels for two powerful squadrons and placed one under the command of Commodore Stephen Decatur.

With the new frigate Guerriere (named after Constitution’s famous prize) sailing as flagship, Decatur’s squadron included Constellation, Macedonian and a number of smaller vessels. On June 17, off Cape de Gata, Constellation’s lookout spotted the Algerian frigate Mashuda. Three of the American squadron drew within range and engaged, overwhelming the Mashuda and forcing its surrender. On June 30, Decatur signed a treaty restoring peace and, after a few port visits in the Mediterranean, returned to New York by early November.

The return of Decatur’s squadron marked the end of an era. Since its founding the United States had been almost constantly embroiled in wars that imperiled the very existence of the nation. Now the American republic was firmly established as a national entity with which to be reckoned. For this, much of the credit must go to the navy.

The Antebellum Period

Between the end of the War of 1812 and the beginning of the Civil War, the United States Navy matured into an organization capable of serving the needs of a dynamic and ambitious people. President Andrew Jackson lauded the navy for the way it represented America’s glory abroad in peaceful and warlike pursuits alike: “Our Navy, whose flag has displayed in distant climes our skill in navigation and our fame in arms.”

During the antebellum period, innovations in propulsion and ordnance began the revolutionary transformation of the navy from a fleet of wooden sailing ships, armed with smoothbore cast-iron guns firing solid shot to, on the eve of the Civil War, iron-hulled steamships, armed with rifled wrought iron–shell guns.

Possessing a diversity of skills and interests, members of its officer corps made significant contributions to science in the fields of geography, astronomy, navigation, oceanography and ordnance. During this period, reformers sought to keep the navy progressive: giving younger officers better hope for promotion; making enlisted service more attractive; improving training; strengthening the administrative structure; and modernizing propulsion, ordnance and ship design. A movement for the systematic training of aspiring naval officers led to the 1845 establishment of the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis.

Pseudo–Combat Operations

With peace prevailing in Europe in the following decades, the principal missions of the U.S. Navy proved to be the protection of commerce, suppression of piracy, enforcement of anti–slave trade laws and agreements and the promotion of diplomacy. For these missions, maneuverable sloops and schooners that could operate in shallow bays and streams were best suited. The navy stationed squadrons in the Mediterranean, in the West Indies, off West Africa, in the Pacific, off Brazil and in the East Indies. These squadrons generally did not act in unison, but vessels patrolled individually, reporting regularly to the flagship.

Pirates infested the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico, important markets for U.S. products, during the tumultuous wars of independence in Spanish America. Between 1821 and 1826, the U.S. West Indies Squadron pursued a vigorous campaign that effectively suppressed West Indian piracy.

Congress in 1800 outlawed the participation of U.S. ships and crews in the transportation of Africans as slaves to Cuba and Brazil; in 1808, it forbade the importation of slaves into the United States; and, in 1820, it made involvement of U.S. citizens in the international slave trade an act of piracy punishable by death. Congress assigned to the U.S. Navy responsibility for enforcing these laws, which became a primary task of the African and Brazil Squadrons.

In 1819, the Slave Trade Act authorized the president to cooperate with the private American Colonization Society in the resettlement in Africa of Africans found on illegal slavers. After 1842, the navy stepped up its antislavery patrols, in accordance with the Webster-Ashburton Treaty between the United States and the United Kingdom, which pledged each nation would maintain a certain number of antislavery cruisers off West Africa.

The navy employed force to protect, and diplomacy to promote, the interests of American merchants. In a typical punitive expedition, a force of 282 seamen and marines from the frigate Potomac landed at Quallah Battoo, on the west coast of Sumatra, in 1832. They killed more than one hundred of the defenders and burned the town as punishment for the massacre of many of the crew of the merchant ship Friendship, of Salem, Massachusetts, and the plundering of the ship the previous year.

Arm of Diplomacy, Vehicle of Exploration

Throughout the era, the United States employed its naval forces in seeking agreements that would protect American sailors stranded abroad and that would open foreign commerce to the United States. Early successes of such efforts came in 1833, when the king of Siam and the sultan of Muscat both signed commercial treaties with the United States.

The greatest diplomatic triumph of the era was the Treaty of Kanagawa between the United States and Japan, negotiated by Commodore Matthew C. Perry in 1854. The shogunate had closed Japan to all foreign intercourse since the beginning of the 17th century. Access to Japanese ports became important to the United States with the growing activity of American whalers, the acquisition of ports on the west coast of North America and the expansion of trade and development of American steamship lines across the Pacific Ocean. Perry arrived in Tokyo Bay in July 1853 with two paddle frigates and two sailing sloops-of-war and delivered a letter from President Millard Fillmore to a direct representative of the emperor. Early in 1854, he returned. Through a combination of firmness, dignified behavior and display of force, Perry won a Japanese guarantee of protection for U.S. citizens and access to two ports for American shipping.

The United States South Seas Exploring Expedition, led by Charles Wilkes, explored the Antarctic and the Pacific Oceans between 1838 and 1842. This expedition of six U.S. naval vessels conducted hydrographic surveys and astronomical observations, and charted navigational hazards. Among the squadron’s accomplishments were surveying 280 islands, charting the coast of the Oregon Territory and demonstrating that Antarctica is a continent. The expedition’s collection of natural history specimens and ethnographic artifacts became the nucleus of the Smithsonian Institution’s collection in 1858.

Meanwhile, Lieutenant Matthew Fontaine Maury, called the “Pathfinder of the Seas,” used his position as director of the Naval Observatory in Washington, D.C., to advance both pure and applied science in meteorology and hydrography. He produced charts of reefs, shoals and other navigational hazards. His charts of seasonal changes in winds and currents enabled sea captains to select routes that sped their journeys.

New Waves of Warfare

The Second Seminole War, 1835–1842, was the longest and costliest of the Indian Wars fought east of the Mississippi. A naval blockade of the Florida coast prevented gunrunners from supplying weapons to the Native Americans. The navy also conducted amphibious operations against the Seminoles. The navy assembled a special squadron of shallow-draft vessels, the “Mosquito Fleet,” to mount expeditions into the interior by way of Florida’s inland waterways. Riverine warfare, sometimes conducted in conjunction with the army, helped bring the war home to the enemy.

The navy also played a major role in securing victory during the Mexican War, 1846–1848. By blockading Mexico’s port cities, the navy strangled Mexico’s maritime trade and prevented its forces from threatening U.S. operations from the sea. The navy directed the landing of General Winfield Scott’s troops at Vera Cruz and participated in the bombardment of that city. By establishing and maintaining sea control, the navy enabled the army to seize and garrison enemy territory. Naval forces, assisted by a relatively small number of infantry soldiers, then seized California for the United States.

The Mexican War left the nation with two sea coasts to defend, propelled the United States into Pacific affairs and provided impetus for the navy’s expansion. The war also left a body of tactical experience on which officers in the Northern and Southern navies would draw during the Civil War.