Abraham Lincoln or George McClellan? A platform to continue war and reunite the nation or a platform to seek peace even at the cost of division and possible continuation of slavery? Voters in the Election of 1864 had choices that would set a course and meaning of the Civil War for the nation. Some of the voters wore blue uniforms and had enlisted in United States armies; did these soldiers have the chance to make their voices and beliefs heard at the ballot box?

The Election of 1864 presented voting challenges and a discussion of absentee voting. With thousands of men of voting age and qualifications serving in the Federal Army, states grappled with the idea if these volunteer soldiers should be allowed to vote and, if so, how to ensure a fair and honest election. The American Civil War had started in 1861 and continued during the election year. Southern states who had declared secession in 1860 or 1861 and not returned to the union were not participants since they saw themselves as a separate country with their own president and government. Voting in the 1864 Election did occur in Louisiana and Tennessee which had been occupied by United States troops; however, their electoral votes for Lincoln were not included due to their recent rebellion status. Three new states participated in the election for the first time: Kansas, West Virginia and Nevada. In northern and border states, local officials, state office holders, congressional representatives and governors were on the ballots for the Election of 1864. However, much of the focus centered on the presidential election and the political parties’ platforms regarding the continuation or outcome of the Civil War.

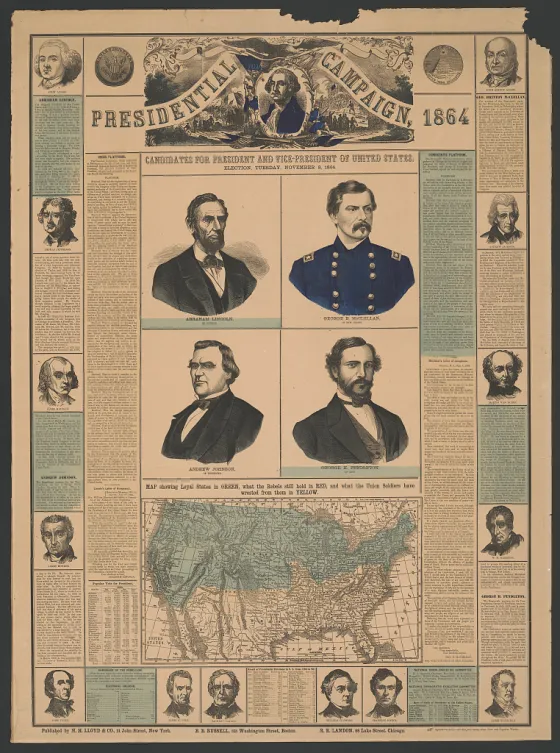

The Republican Party experienced a brief split during the candidate nominations. “Radical Republicans”—a name they chose for themselves—briefly formed the Radical Democracy Party and nominated John C. Fremont as their presidential candidate. Fremont withdrew his nomination and endorsed incumbent Republican president, Abraham Lincoln. Meanwhile, “War Democrats”—members of the Democratic party who supported ending the Civil War through military victory and reuniting the country—joined with Republicans and called themselves the National Union Party, nominating Lincoln for a second term. The National Union Party added a new vice president nominee to their ticket; Andrew Johnson from Tennessee symbolized the idea of political unity to achieve national unity again. The Republican Party platform emphasized continuation of the war until the Confederacy surrendered, the need for a constitutional amendment to abolish slavery, continuing to enforce the Monroe Doctrine and keeping Europe out of the American conflict, aid for Union veterans and western expansion with a transcontinental railroad.

The Democratic Party was also divided and tried to find a compromise between their platform and presidential candidates. War Democrats supported finishing the Civil War with Union victory and reuniting the country. Peace Democrats split between moderates who wanted a negotiated peace for a Union victory and Radical Peace Democrat “Copperheads” who were willing to end the war without a Union victory. The Party nominated General George B. McClellan for president, and he supported ending the war with Union victory. However, the vice president nominee, George H. Pendleton, had anti-war and peace with compromise views. The party’s platform emphasized ending the war through peace, not necessarily with victory or reunification. McClellan—a former Union general—opposed the party’s platform but remained their presidential candidate.

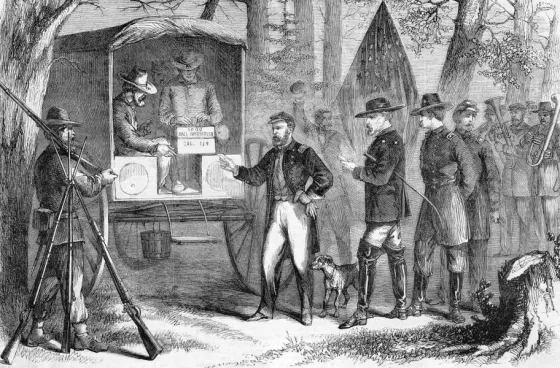

For the first time since 1812, a presidential election occurred during a war. As voting rights had expanded for male voters in the mid-19th Century, the challenge of letting volunteer soldiers vote in the election became a much-discussed topic. Voting qualifications were still controlled by states; women were not allowed to vote, and only a handful of northern states allowed African American men to vote. Absentee voting came under discussion and was allowed for the first time in United States history. Plans were also put in place for soldiers to vote in their military camps. For northern states that did not allow absentee voting, provisions were often made for soldiers to be sent home for furloughs to vote in their hometowns during the autumn months. Nineteenth Century-style conspiracy theories ran wild that voting fraud would be rampant through the methods of allowing soldiers to vote. Election officials made extra efforts to ensure the honesty of the election, and most voting soldiers also took their vote and method of casting a ballot seriously.

Voting in the 1860s did not include secret ballots, so whether voters cast their ballots in their hometowns or in a military camp, their votes were not secret. Voting was seen as a community and civic event, and the “community” of soldiers in military camps during the Civil War became a key voting bloc in the 1864 Election.

The outcome of campaigns and battles where soldiers literally fought impacted the election and the soldiers’ vote was also recognized as an important voice for the outcome of the conflict. Both militarily and politically Union soldiers showed their preference for a victory outcome and national unity—even though that meant they would stay, serve and fight through the end of the military conflict.

Throughout the summer of 1864, Confederate victories and high Union casualties filled the newspapers. Battles like Mansfield, Cold Harbor, Brice’s Cross Roads, Kennesaw Mountain and The Crater put Confederate triumphs into the headlines. However, overall campaign success swung in the Union’s favor as United States Armies continued to advance and captured key strategic Confederate strongholds despite heavy losses. The Overland Campaign in Virginia eventually pinned the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia at Petersburg and put pressure on the Confederate capital at Richmond. The United States navy and army captured Mobile Bay in Alabama during August 1864. Then, Union troops under General William T. Sherman captured Atlanta, Georgia at the beginning of September 1864 and pushed another strategic victory into the headlines. Peace Democrats highlighted the high casualties during these campaigns, but the National Union Party focused on the larger victories, pointing to them as a sign that the war would end with a victory and reunification of the country.

Politics and the election filled letters between soldiers and their correspondents on the home front. Though women could not vote, they often participated in local political gatherings and had strong opinions on state and national candidates. Women sometimes encouraged soldiers to vote in certain ways or took an interest in hearing how the men planned to vote.

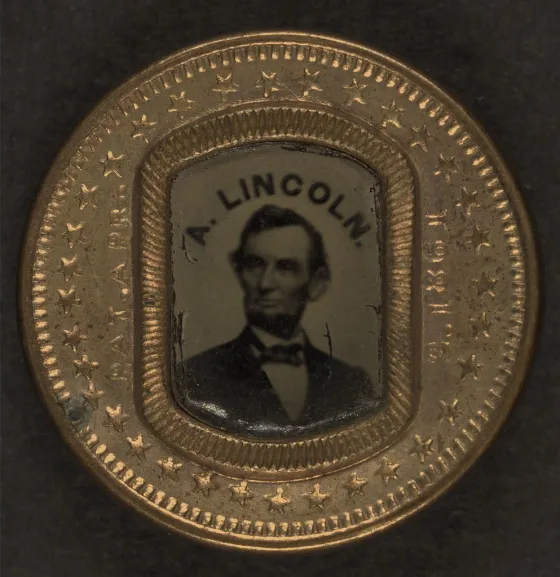

Uncertainty hung over the soldiers’ vote. McClellan had been a popular Union general, still beloved by many of the soldiers who had marched under his command. However, Lincoln and the National Union Party stood for a victory that would reunite the country and give meaning the sacrifices and losses the soldiers had witnessed or suffered. For soldiers who also wanted to see the abolition of slavery, victory and voting with the National Union Party offered a better chance of success for that goal and a constitutional amendment. Many soldiers influenced their home-voters and their comrades to vote—usually for Lincoln’s re-election and with harsh words toward “Copperheads” and peace without victory. Aware of the recent battlefield victories—some of which they had fought to win—soldiers understood the folksy slogan of the Lincoln campaign: “Don’t change horses in the middle of the stream.” Military victories were adding up, and the end of the Confederacy and the war was in sight through victory.

Throughout Union army camps in the autumn of 1864, soldiers lined up to cast their ballots or election tickets into the box for their preferred party and candidate. These votes would be counted with the others of their state and help determine the political fate of the country. The recent victories at Mobile Bay and Atlanta and the near immobility of Lee’s army at Petersburg kept the chances of Union victory strong, influencing both the home front and soldier vote.

Confederates knew a political victory for the Democratic Party would give them their best change in 1864 for separation and a quick end to the war through the efforts of the Peace Democrats who splits and influenced that party in this election cycle.

In Union camps along Cedar Creek in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, soldiers took a break from weeks of fighting and destruction of supplies. They had won a series of Union victories at the Third Battle of Winchester, Fisher’s Hill and Tom’s Brook. They rested, waited for orders and lined up to vote in their camps. General Rutherford B. Hayes—a future U.S. President—was on the ballot for elected office in his home state of Ohio, and he took particular interest in the political scene both in camp and at home.

The Confederates in the Shenandoah Valley commanded by General Jubal Early launched a surprise attack on the Union camps in the early morning hours of October 19, 1864. Early hoped that a Confederate battlefield victory might sway votes and put the election in the Peace Democrats favor. For a time, the Battle of Cedar Creek looked like it might be a Confederate victory. Divisions of surprised Union soldiers fled from their camps. Some officers and men secured the ballot boxes and took them along in the retreat. However, delaying action and the rallying of Union troops brought the retreat to a halt. The arrival Union General Philip Sheridan on the battlefield provided enthusiasm and inspiration, and by mid-afternoon, Union soldiers counterattacked. By nightfall, the Battle of Cedar Creek was a Union victory. No defeat from Cedar Creek could crowd the headlines in northern newspapers. Instead, the reporting of a dramatic Union victory—perhaps overdramatized by Sheridan himself—provided an “October Surprise” and another military victory for Lincoln and the National Union Party.

When the votes were tallied across the northern states—including the votes of soldiers in distant camps—President Lincoln had won a second term with 55% of the popular vote and 212 electoral votes. McClellan won the electoral votes of just three states: Kentucky, Delaware and New Jersey. Of the 40,247 Union soldiers who voted, 30,503 voted for Lincoln—75.8% of the Union citizen-soldiers.

A few months after the election, President Lincoln took the oath of office for the second time in March 1865. In his second inaugural address, he shared his hopes for reuniting the country after the end of the Civil War:

"With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nations wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations."

While all Union soldiers did not agree with Lincoln’s ideals, they had voted and continued to fight for victory. These citizen-soldiers would be part of the path beyond the war, finding peace and redefining their victories in the decades ahead. The experiences of soldiers in the Civil War influenced their votes for years to come, and the usage of absentee ballots during 1864 also added new voting precedents to the American quest for democracy and voting rights.

Further Reading:

- Reelecting Lincoln: The Battle for the 1864 Presidency by John C. Waugh (2009).

- Emancipation, the Union Army, and the Reelection of Abraham Lincoln by Jonathan W. White (2014).

- Decided on the Battlefield: Grant, Sherman, Lincoln and the Election of 1864 by David Alan Johnson (2012).

Related Battles

3,722

5,500

5,764

3,060