I got interested in photography through my high school teacher, Bertram Lewis. He looked at work that I had done as a sculptor and said, “Tony, it’s pretty good but, you know you are a born photographer, and don’t you ever forget this.”

I went into the army as a private. I never volunteered for anything; because war is something you don’t volunteer for. I approached the army to become a photographer, but they said, “You are too young for us.” I responded, “Sir, I am old enough for this gun and not old enough for this camera?” He said, “That's pretty funny, but you still are too young for us.”

And that was it, I was in the army. I made the landing in Normandy, and I fought in many battles in Germany, getting wounded along the way, but made it all the way to Berlin. I was with the 83rd Infantry Division, what was known then as the Ohio Division. I was both a photographer and a soldier. It seems like a contradiction, but that's what it was. When bullets were close to you, you don't use the camera; you use your rifle.

I took pictures for myself, and luck led me to take just about the best war pictures of all time. All I wanted to produce was the best pictures to make sure that after the war I would have a job as a photographer. In the field, I processed my film in a series of four metal helmets. I removed the plastic, and I used them as the darkroom trays: First helmet was the developer, then water, then highpool, then water. So, I needed my own helmet, and three borrowed ones. I was doing this at the light of the moon at night. Crazy, but I got along. And I still have those negatives.

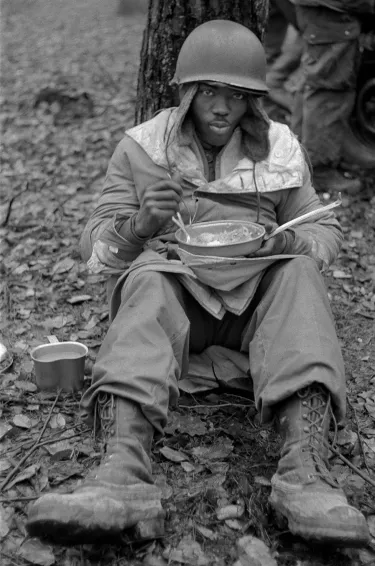

I never wanted to be a fighter, but I always wanted to be a photographer. I decided to photograph portraits of the people in my unit, because they were the people I lived with. We slept together, we risked together. We did so much together. I never saw soldiers. I saw human beings. I saw red blood, human blood. The battlefield, in a way, helped me, because when the war is on. that’s all that it is, fighting all the time. You know that it can happen to you. What do you do about it? I took pictures — the GI kissing the little girl — because in the end, we are humans. It's not a war picture — that GI could have been civilian. A love for our children is universal. That's what I was doing, along the line of humanity, where a professional army photographer would have gone for the business part of it.

The 83rd Infantry Division had a kind of a little newspaper that came out monthly, and eventually I went to work for that. But, the army, in truth, never offered me any guide, any help. I never got a roll of film from them. The official photography department considered me an outsider. The army really did not want me to take real combat pictures, because in a way it would scare young men from volunteering to go in the army. So I accommodated them, made believe as if my pictures were not important. I perhaps might have been more famous if I had done things differently.

My pictures were used very quickly at the end of the war, but the army had a tough time selling their pictures. One of the reasons was they used four-by-five cameras, while I used 35-millimeter, an Argus C3. And when you enlarge 35-millimeter, you get a little roughness in your images that makes a picture more of a war picture. It’s not too polished, because war should have grain.

To go through a war is never easy, but I made it. The first time I was wounded, it was in Normandy, and it was my arm. Nothing serious, but blood came out, so it's a wound. Then the next time was in Belgium. Then the last time was in the Hurtgen Forest. But I was lucky. I was lucky to have made it through the war.

Every time you get out of the foxhole, you endanger yourself. A few times, when you cannot deal with a situation, you cry like a baby. You actually sweat. There’s no time to sweat, but your body, your mind, your ideas impose this …, how could I say it? A certain sensation that you could get killed any minute. War is hell. It’s been said before, but it’s true.

We call each other German, French, Italian. There is no Italian blood. There is no French blood. It's human blood. On this Earth there is one humanity. Let's do something about it. Let's live! In a way, photography was my way of telling the world, “We have better things to do than to kill ourselves.”

One of my most famous pictures shows a burning German soldier, and it’s a frightening image. It happened in Hurtgen Forest, about a mile inside of Germany from Belgium. It was winter, and some stupid people built fires where there’s no room for fire. I think that this man must have been inside of the tank and once we knocked the tank out, he tried to escape. As he came out, apparently gasoline got all over him. In the picture that I have, he’s actually in flame. I was 19 years old when I took that picture, and I could hear what the German soldier was saying. Just one word —“mother” — and, eventually, he didn't talk anymore.

A good war photograph tells man to grow up. It’s about time we make the universe universal. Period. As long as we make these divisions — Germans, Italian, French, Jews and not Jews — we are going to kill ourselves.

I consider my best wartime photo to be of a single dead man in the snow with his rifle. That's a frightening picture; to me it has the message that we should play with children, not with guns. I took that picture, believe it or not, because he was beautiful. When I saw that, I went close and I actually felt his arm because, you never know if something is still alive. I took the bayonet and chopped away the ice to find out when was he killed. Two, three minutes ago? An hour ago? A day ago? I didn't know. And his arm was frozen, so he had died, perhaps, a few hours earlier, before it began to snow.

I'm always happy when wars end. Mankind doesn’t need them. We’re repeating the same mistakes Julius Caesar made, having wars. Poor mankind. As I talk now, there are people killing in some stupid war. I can't believe that we learned nothing from Mussolini and Hitler and Hirohito, three men who wanted to destroy the world.