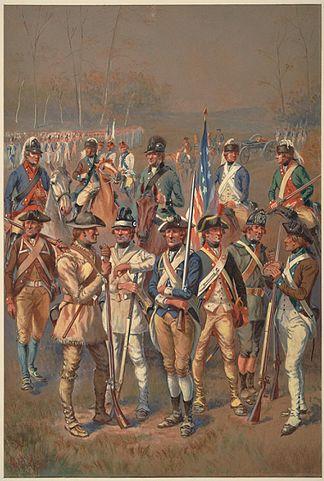

The Continental Army was established by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of hostilities at Lexington and Concord and predates George Washington’s assumption of command outside of Boston in July 1775. Most men who served in the Continental Army were between the ages of 15 and 30. Those who served in the Army were merchants, mechanics, and farmers. By 1780, close to 30,000 men served in the Continental Army, which was dispersed throughout the new nation.

It is also important to note that each state raised militia units. The British government established state militias after the French and Indian War to alleviate the need to garrison expensive regular soldiers in the colonies. All military aged males, aged 16 to 45, were required to serve in the militia and maintain the necessary arms and equipment for military service. During the Revolution both Loyalist and Patriot militias were called out to supplement the regular forces of both sides.

Prior to 1777, enlistment in the Continental Army was of various durations but generally for a year of service. After 1778, Congress changed the rules and men served for either three years or the duration of the war. In some cases, bounties were paid to entice men to enlist or for men who chose to serve longer. Bounties could consist of additional money, additional clothing, or land west of the Ohio River, where many veterans would settle after the war. A private in the Continental Army earned $6.23 per month and pay would increase upon promotion of rank. Sometimes a promotion in rank brought an increase in food rations and in some cases more money in lieu of rations.

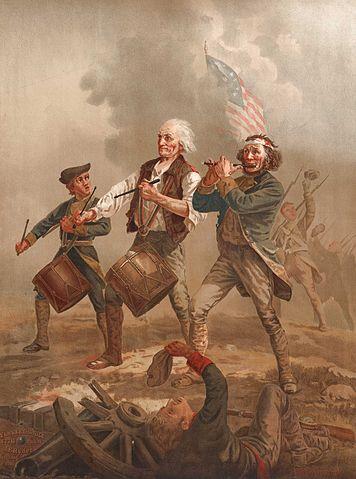

Life in the Continental Army was difficult. It was mundane and monotonous. Generally, when not engaged in combat, soldiers in the Continental Army served three duties: fatigue or manual labor, such as digging vaults (latrines), clearing fields, or erecting fortifications. They also served on guard duty and drilled daily with their musket and in marching formations.

Reveille was typically at daybreak and soldiers cooked one meal per day, generally around 3:00 pm. Whatever food was left over from the meal, soldiers divided and placed in their haversacks to be consumed as needed. Rations were determined by Congress. Each man received 1.5 pounds of meat per day, typically beef. Each hunk they received included not only the meat, but bone, fat, and gristle. They also received one pound of bread per day, which was baked daily inside the camp, or 1.5 pounds of flour to make firecakes. Firecakes were like pancakes. Soldiers heated a flat rock, then mixed the flour with water, meat, gristle, and poured the mixture on the heated rock, then would flip it over to cook the other side.

Soldiers also received two ounces of spirits a day to be added to the water in their canteens to kill vermin or bacteria (although at the time that term was not used) that could be found floating in the water.

Often joining men in the camps or on the march were women and children known as camp followers. The women were mostly the wives of the enlisted men, and George Washington prohibited women of questionable nature to accompany his army. Women and children were also doled out rations. Women received half of what a soldier got and children were give quarter rations. Depending upon the jobs women did while accompanying the army, they could receive more rations.

When on the march, the typical soldier in the Continental Army carried forty-five pounds of gear. This included, when he was properly supplied, his weapon, haversack, knapsack, and other accoutrements including a bayonet, tin cup, bowl, spoon, cartridge box, canteen, and if lucky an extra blanket, shirt, or writing paper and a pen. Men did keep in communication with family from home and would write letters if they could steal a moment to sit down and write to a loved one. Supply problems constantly plagued the Continental Army, and often men simply made do with whatever arms and equipment they could bring from home.

When drilling with the musket, men were pushed in training to fire four rounds per minute or one every 15 seconds. The best soldiers could squeeze off five rounds per minute. Drill with a musket lasted for eight hours a day. The best regiments to serve in the Continental Army were from Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania. African Americans did serve in the ranks of the Continental Army and General James Mitchell Varnum petitioned Congress to permit integration. Thus some fighting units were integrated. This would not happen again until 1950, when the US Army fought in Korea. The First Rhode Island Infantry was an entirely African American regiment.

Punishment for infractions in the Continental Army was severe and ranged from receiving lashes to death. A soldier’s execution could be delivered for desertion or for failing to use the vaults, slit trenches dug to hold human waste. Executions were done in public as a demonstration to other soldiers to keep them in line.

Sanitation was a significant concern in the Continental Army. Even though information about hygiene in the 18th century was limited compared to what we know today, the results of poor sanitation were well understood. For each soldier killed in combat, nine died of disease, mostly attributed to a lack of sanitation.

The biggest frustration for Continental Army soldiers was the ineffectiveness of Congress and the lack of support they received from the political body that espoused the same cause. Mutiny at times raised its head. This would play a role in the future of the nation after it was created, with those arguing for a strong central government, basing their arguments on the limited ability and lack of performance by Congress during the war.

Related Battles

93

300