In many respects the American Revolution was the progeny of the Enlightenment, that 17th century intellectual movement in Europe that sparked new ideas about humanity, science, government, and reason. The most influential European philosopher on the American Revolution was Englishman John Locke, who at the end of the 17th century expanded the notion of the social contract between those governed and those governing. Locke’s philosophy of the “social contract” greatly influenced Thomas Jefferson and its themes can be found throughout the Declaration of Independence.

But Locke’s philosophy and the works of other Enlightenment thinkers also influenced many noblemen and men of privilege living in Europe in 1776. Including individuals with a military pedigree who were excited and energized at the possibilities for humankind that the new United States offered to the world. Many of them wanted to be part of the historical moment. Representing the United States abroad to foreign governments from Paris, was the wily and savvy Benjamin Franklin. Franklin would be the portal through which many of these foreign fighters found their way to the new United States. The lure of a high rank in the nascent American Continental Army played a role as well yet to view these men simply as bounty hunters is a disservice to their memory. The zeal of freedom was firmly entrenched in their hearts and minds.

While the young Marquis de Lafayette was the most visible foreign presence in the Continental Army, men from Poland and the various German States also served the American cause. Thaddeus Kosciusko and Kazimierz Pulaski hailed from Poland, Johan DeKalb was from Bavaria, Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben a native of Prussia, and Louis Lebeque DuPortail, like Lafayette, was from France. These men all served within the structure of the Continental Army, made significant contributions to various aspects of the war’s efforts, and in the case of Pulaski and DeKalb, gave their lives to the cause.

The twenty-one-year-old Marquis de Lafayette, whose full name was Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Gilbert du Mortier de Lafayette, son of a French nobleman, was recruited into the American Army by another equally shrewd American agent. Silas Deane promised high rank and played into the temptation of glory for the young in December 1776. Lafayette embraced the ideals of the enlightenment and as early as 1775 claimed, “My heart was dedicated.” Negotiations between Lafayette and American agents had to be done in secrecy. France at the time was not officially at war with England. Though many in France were keen to find a way to extract revenge on Great Britain after the sting of losing Canada to them in the French and Indian War.

Lafayette left France for the United States surreptitiously in April 1777. He gladly paid for his travel aboard a ship fittingly named La Victorie, as the Continental Congress had no funds to offer him. He arrived in South Carolina in June 1777 and traveled north to the American capital Philadelphia, where he was introduced to George Washington. Washington was smitten with the young Marquis and brought him into his close family of officers. In many respects Washington became like a father to Lafayette and Lafayette enjoyed his place as a somewhat adopted son (George Washington had no children of his own, but rather two step-children with his wife, Martha.) At the Battle of Brandywine in September 1777, Lafayette bravely entered the fighting guiding an orderly retreat of American troops before suffering a leg wound. After recovering from the calf wound, Lafayette shivered at Valley Forge during the American encampment that winter and again saw combat with a better trained Continental Army at Monmouth, New Jersey in June 1778. His devotion to Washington lasted throughout the course of the war.

In 1779 he returned to France and was immediately placed under house arrest “for disobedience to King Louis XVI” in the way he left in 1777 to serve in the American cause. His confinement lasted eight days. By now France had become a full-fledged partner to the Americans, so when Lafayette was released, he was warmly received by the King.

In December 1779, Lafayette’s wife, Adrianne, had been married since 1774, had a son and Lafayette immediately named him Georges Washington Lafayette.

During his tenure at home, Lafayette continued to promote the American cause and push for more French support. Lafayette returned to the United States in April 1780 and, still as a member of Washington’s staff, served as a translator and liaison between Washington and French General Rochambeau, commander of the French forces sent to America, when The French Army arrived in the United States.

During his tenure at home, Lafayette continued to promote the American cause and push for more French support. Lafayette returned to the United States in April 1780 and resumed his position as a member of Washington’s staff. The Frenchman served as a translator and liaison between Washington and French General Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau, commander of the French forces sent to America, when the French Army arrived in the United States.

By 1780, the theatre of operations had shifted to the South. After Horatio Gates was soundly defeated in South Carolina at Camden, the Continental Army in the Southern Department was in shambles. Daniel Morgan’s stunning victory at Cowpens, South Carolina in January 1781 lifted American spirits and raised hope in the Southern Department. After dispatching Nathanael Greene to assume overall command, Washington ordered Lafayette to head south as well and work alongside another foreign officer who joined the American cause, Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben.

Friedrich Wilhelm August Heinrich Ferdinand Steuben, better known as Baron von Steuben, was a Prussian officer who is credited with forming the amateur Continental Army into a professional fighting force. Von Steuben was a captain in the Prussian army and aide-de-camp to Fredrick the Great. French Minister of War Claude Luis, Compte de Saint-Germain recommended von Steuben to Franklin as an able staff officer in need of a job. Franklin exaggerated von Stueben’s qualifications to Washington, calling him a “Lieutenant General in the King of Prussia’s service.” Von Steuben arrived in North American in December of 1777, making his way to the encampment at Valley Forge by February. Washington, in desperate need of professionals, appointed him as Inspector General.

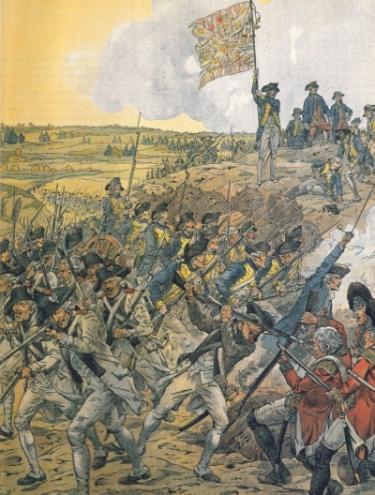

Despite his inflated qualifications, von Steuben was every bit the professional soldier, and immediately set about inspecting the rag-tag Continental Army. During the fateful winter at Valley Forge, von Steuben trained and drilled the army, reformed the administration, and increased sanitation. By the time the army left Valley Forge it was a force capable of standing up to British Regulars. The Battle of Monmouth proved the effectiveness of von Steuben’s reforms, with American Continentals standing against the Regulars. Von Steuben published his famous “Blue Book,” the first training manual for the American army. After the war von Steuben remained in the United States, dying in 1794.

Together, Lafayette and von Steuben would shadow British forces in Virginia. By the fall of 1781, Lafayette and Washington were reunited as the allied American and French Armies entrenched at Yorktown, Virginia, besieging British General Lord Charles Cornwallis. Continental successfully captured British Redoubt #10, while French forces captured Redoubt #9 tightening the noose around Cornwallis. On October 19, 1781 Cornwallis surrendered his army, ending major military operations in the American Revolution. By the fall of Yorktown Lafayette was a bona fide American hero.

After the war, Lafayette returned to France and found himself caught up in the bloody chaos of the French Revolution. For a time he was imprisoned and then later released.

In 1824, Lafayette returned to the United States and toured the growing nation in a triumphal manner befitting a head of state, to which the Frenchman was not. Among the places he visited was Mount Vernon to pay his respects at George Washington’s Tomb. He made good on his promise, too, to visit all of the states. The day after his 68th birthday the White House hosted Lafayette. On September 6, 1825, he left for home. He died in 1834 and America officially mourned his loss. By order of President Andrew Jackson, the nation was directed to mourn Lafayette as it had mourned George Washington upon his death. Both chambers of Congress were draped in black bunting for thirty days.

In 2002, the United States Congress voted to give Lafayette the status of honorary citizenship. Lafayette’s American biographer, historian Marc Leepson, argues in his 2001 examination, Lafayette: Lessons in Leadership from the Idealist General:

“The Marquis de Lafayette was far from perfect. He was sometimes vain, naïve, immature, and egocentric. But he consistently stuck to his ideals, even when doing so endangered his life and fortune. Those ideals proved to be the founding principle of two of the world’s most enduring nations, the United States and France. That is a legacy that few military leaders, politicians or statesmen can match.”