The Spanish forces led by Bernardo de Gálvez at the Siege of Pensacola.

Schoolchildren learn about the 13 colonies that declared independence in 1776, but in the 1760s, Great Britian acquired other strategic possessions on mainland North America, in addition to its Caribbean holdings. The treaty that ended the Seven Years’ War stripped France of its territory in what is now Canada, and Spain gave the British Florida in exchange for reclaiming Havana, Cuba, which had fallen to siege in 1762.

The vast majority of North America’s Spanish population relocated to Cuba, and Britain divided its new territory into East Florida and West Florida, which was soon inhabited by colonists who relocated from South Carolina, Georgia and Bermuda. Others came from England, including veterans of the Seven Years’ War who’d been given land grants for their service. With such a demographic, it remained solidly loyalist during the Revolution, and although both Floridas were invited to send delegates to the First Continental Congress, they declined. Later, using Georgia as a staging ground, the Continental Army launched multiple attempts to capture East Florida.

With the colonies to the north rebelling, Florida was crucial to the British war effort, keeping open a supply chain from the British Caribbean colonies. The port at St. Augustine was especially vital, and this hub for stockpiling goods, troops and weaponry was a tempting target for Continental forces.

General George Washington authorized five attempts to capture Florida, though only three were carried out. The first major invasion occurred in August of 1776 when Major General Charles Lee and Major General Robert Howe attempted to capture St. Augustine. Lee and Howe marched south from Savannah, Georgia, with 2,500 men. But mass desertions due to lack of supplies and poor planning caused the mission to be aborted.

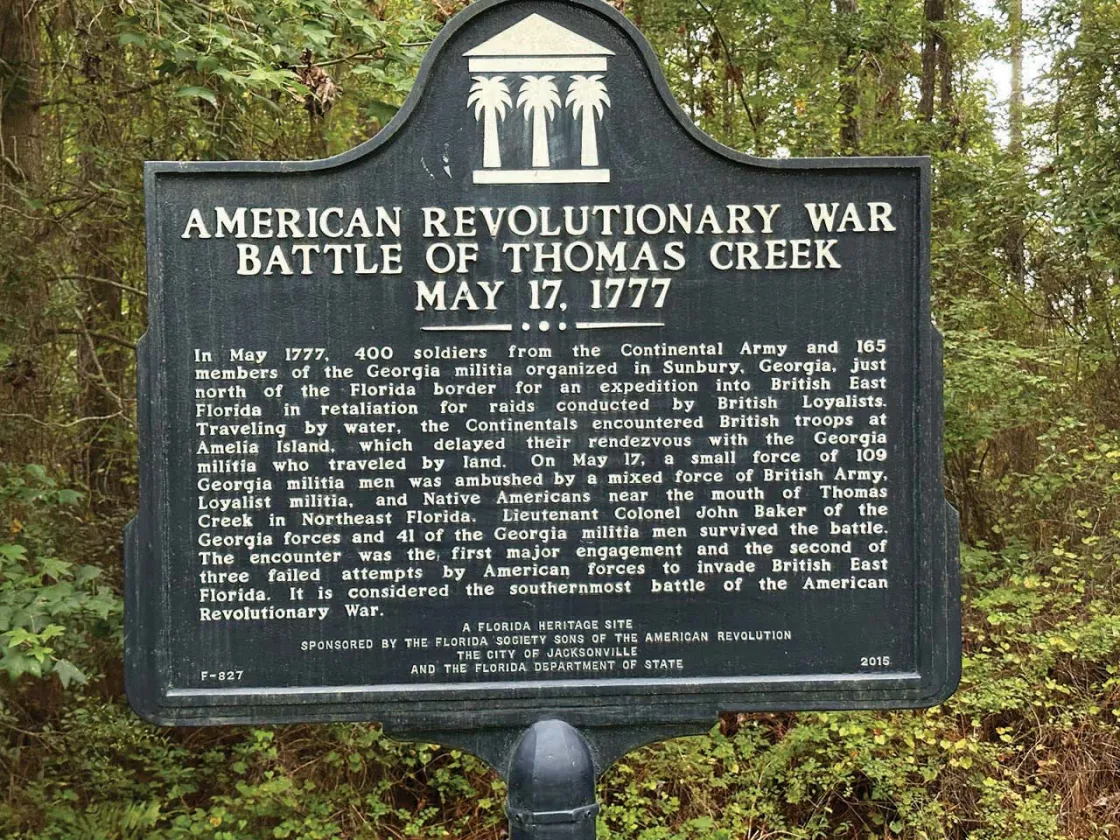

The Battle of Thomas Creek marked another failed attempt by the Continental Army to gain control of East Florida. In May 1777, Continental forces crossed out of Georgia to gain a foothold on the far side of the St. Mary’s River. However, loyalist Thomas Brown with his East Florida Rangers, Native American allies and British troops launched a surprise attack on the Continentals campsite at Thomas Creek. Outnumbered and ill-prepared, the Continental forces retreated, leaving Brown and his Rangers free to continue raiding into south Georgia.

In January 1778, Major General Howe planned a third East Florida invasion, hoping to rely on Continental regulars. But when he was forced to proceed with the Georgia militia, Thomas Brown and his Rangers took advantage with a surprise attack at Fort Barrington that forced the Patriots’ surrender.

Despite the setback, in May, Howe continued his efforts chasing Brown’s forces into Florida. On June 28, Howe sent Colonel James Screvin to attack Brown and the British at Fort Toyn. However, a combined British force of nearly 1,000 soldiers, loyalist militia and Native Americans overwhelmed the American forces at the Battle of Alligator Creek Bridge. Again outmatched, Screven retreated. Although Washington sought further expeditions to invade East Florida in late 1778 and 1780, blocking St. Augustine’s role as hub for British operations, they went unexecuted, leaving East Florida under British control for the rest of the war.

Being farther from the population centers in Georgia, West Florida — which stretched along the Gulf Coast as far as the Mississippi River and included coastal portions of what is now Alabama and Mississippi, as far as Baton Rouge — faced fewer early invasions. The notable exception was the Willing Expedition, beginning in the winter of 1778. Continental Naval Captain James Willing was sent as an emissary by Congress to invite West Florida to become the 14th state. Although more sympathetic than their eastern equivalents to the American cause, local leaders were more concerned by the threat posed by New Orleans and Spanish Louisiana.

Rebuffed, Congress then authorized Willing to lead troops into the region so that the population would swear an oath of neutrality. He plundered plantations in West Florida and indicated that General George Rogers Clark and some 5,000 militia would follow in his wake, securing oaths from the citizens of Natchez and other areas. Eventually, a loyalist force defeated Willing’s raiders, and he sought protection in New Orleans, from which the Spanish had allowed his operations. Ultimately, his vessel was intercepted during a return Atlantic voyage to Philadelphia, and he was held on a prison ship in New York for at least a year.

Then, in May 1779, Spain entered the war indirectly — as an ally of France rather than the United States — dramatically shifting the balance of power on the Gulf Coast. With colonial governors authorized to engage in direct hostilities with the British, Bernardo de Galvez in Spanish Louisiana moved quickly, setting out from New Orleans in August with a diverse force that grew to include Spanish regulars, militia, free Blacks, Anglo-American volunteers, Native Americans and Acadians — colonists from New France (now the Maritime Provinces of Canada and parts of Maine) who had been forcibly relocated to Louisiana after the British took control of the region in the same post-war shuffle that had given them control of Florida. By May 1781, they had captured Baton Rouge, Mobile and Pensacola, prompting the surrender of all West Florida by the British

Related Battles

32

11