The American Revolution produced many future leaders in the political sphere for the newly created United States of America. A few became president of the new country. The most notable, of course, was George Washington, commander of the Continental Army, and the most recognizable face from the war to transition into the world of politics. However, the Virginian was not the only former soldier to be voted into the top position of the government. In fact, there were two others that can claim that accomplishment as well.

James Monroe was born in Virginia on April 28, 1758, a stone’s throw from where Washington took his first breath 26 years earlier. He became the fifth president of the United States. His family was prosperous, his father a planter that supplemented income with carpentry. Along with James, his father, Spencer and wife Elizabeth had four other children in the following order; Elizabeth, then James, Spence, Andrew, and Joseph Jones. When James turned 11, he attended a local school where he met John Marshall. Marshall became a lifelong friend and was destined to be one of the greatest Supreme Court Justices in American judicial history.

Like many families in the 18th century, death was ever-present and within a two-year span beginning in 1772, James lost both his mother and father. Being the oldest, James inherited their property upon the passing of his parents. Unfortunately, this did not afford James the opportunity to stay in school. With younger siblings to support, James searched for an income. Luckily, an uncle, from his mother’s side, bereft of children himself stepped in and became a parent figure for the Monroe clan. James moved to his uncle’s place in Williamsburg and eventually enrolled in the prestigious College of William and Mary. There, James was introduced to such Virginia luminaries as George Washington, Patrick Henry, and Thomas Jefferson.

After catching the revolutionary, anti-British fervor that was running rampant in Williamsburg, James left college after only a year-and-a-half. With the coming of war, James dropped out and enlisted in the 3rd Virginia Regiment, slated to be part of the quota of Continental units from the Old Dominion. Having the benefit of an education, James was elected as a lieutenant and served with a distant relative of George Washington’s, William Washington, the latter to become one of the greater cavalry commanders for the American cause.

Lieutenant Monroe and the 3rd Virginia would see action in the battles around New York and hazard the ensuing retreat across New Jersey, and into Pennsylvania. On Christmas evening, General George Washington led his forces across a frozen Delaware River to surprise a Hessian (a German state that the British had purchased soldiers from to augment the British Army and fight in North America) outpost at Trenton, New Jersey. During the thick of the fighting, James received a nasty wound in the shoulder that damaged the artery. Although knocked out of action, his bravery and daring in the battle attracted the attention of Washington who authorized his promotion to captain.

From this engagement came the most prominent memory of Monroe’s service during the American Revolution; his likeness was included in the 1851 painting “Washington Crossing the Delaware” by German artist Emanuel Leutze. A young Monroe is depicted holding the United States flag. Although Monroe did cross the river that evening, he was not in the same boat as General Washington, nor would he have been a flag bearer.

Following his convalescence and a brief sojourn to Virginia recruit soldiers for a company command, Monroe, through the intercession of his uncle, returned to the Continental army in a staff position with General William Alexander, Lord Stirling. With this new appointment, Monroe would strike up a friendship with the Marquis de Lafayette. The two men came in contact again years later when the Virginian served as the United States Ambassador to France. With a new friendship came the rekindling of an old, as Monroe shared a cabin during the winter of Valley Forge with his former school chum John Marshall.

By December 1778, Monroe, suffering from a lack of money, resigned his captain's commission and ventured to Philadelphia to live with his uncle. When word reached the American capital of the disaster at Savannah, Monroe heard that Virginia was raising regiments to resist the expected northward British thrust. Monroe hurried to Williamsburg with letters of introduction from Washington and Lord Stirling and received one of the lieutenant colonels ranks. However, recruitment for these new regiments was negligible.

Besides a stint in the Virginia militia in 1781, that ended the American Revolutionary military service of James Monroe. With his uncle’s guidance, Monroe turned to the study of law under Thomas Jefferson in Williamsburg. He studied law, was accepted to the bar, and won his first election, to the Virginia House of Delegates in 1782. This victory initiated Monroe’s climb in the political ranks that ended in the Presidency in 1816.

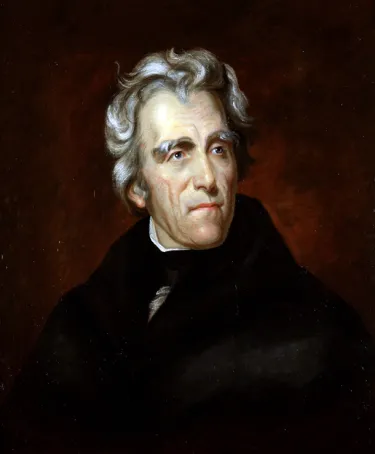

Believed to be born in South Carolina, yet claimed by North Carolina and Tennessee too, the second veteran of the American Revolution to attain the chief executive position was Andrew Jackson. He was born on March 15, 1767. Three weeks prior to Andrew’s entry into the world his father died during a logging accident leaving his widow, Elizabeth Hutchinson Jackson, and her two sons to find residence at her aunt and uncle’s plantation in the Waxhaws region. Andrew was named after his father.

His early childhood included an education from two religious officiants. When war erupted between the colonies and Great Britain, the split in views in the southern colonies led to a fractional civil war. Jackson’s immediate family sided with the Patriots. In the aftermath of the Battle of Stono Ferry, fought on June 20, 1779, Jackson’s family received word that the oldest son, Hugh, had succumbed to heat exhaustion.

As the war turned south, an incident occurred in the Waxhaws that inflamed anti-British passions, when British cavalry leader, Banastre Tarleton caught retreating Continentals under Colonel Abraham Buford. Called the Battle of Waxhaws, the battle was referred to by pro-patriots as the “Massacre at Waxhaws” in which over 110 Continentals were killed, an unknown number while trying to surrender, 150 wounded, and 53 captured out of a total force of 480. British losses amounted to five killed and 12 wounded.

With the fervor that followed, patriot militia was the only effective force available in the south following the loss of the Continental soldiers at Charleston, South Carolina, and the debacle at the Waxhaws for the American cause. Jackson’s mother encouraged her two remaining sons, Robert and Andrew to learn the rudiments of a soldier by drilling with the militia. Service followed with famed militia leader Colonel William Richardson Davie and the Jackson boys saw action at the Battle of Hanging Rock, South Carolina on August 6, 1780.

The following April, both boys were captured by the British. While being detained, both boys claimed their status as prisoners-of-war and refused to clean a British officer’s boots. Andrew was struck across the head and left hand by the sword-wielding Briton. His brother received a strike with the sword as well.

After a few months in captivity, their mother was able to achieve their release and the trio walked over 40 miles to the Waxhaws. Due to the journey and their resultant poor health from their incarceration, Robert rode the only horse most of the way. Incessant rain drenched the trio exacerbating the debilitating effects of smallpox which the boys were suffering from. Within 48-hours of returning home, Robert died.

The two sons were not the only Jacksons to serve the patriot cause. Their mother, Elizabeth, horrified at the way American prisoners were faring in Charleston Harbor, volunteered to be a nurse on the infamous prison ships. Unfortunately, the ships had recently experienced an outbreak of cholera. Elizabeth contracted the disease and passed away. Her remains lay in an unmarked grave.

These dual losses, plus the experience at the hands of the British officer instilled in the young Andrew a vehement hatred of the British that grew during the next and last major conflict between the two countries, the War of 1812. The final battle of the war at New Orleans immortalized Andrew Jackson.

Although a few other future presidents served in some capacity during the American Revolution, including John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison, all three of them served in political roles and never saw service nor action in the military. Another future executive, John Quincy Adams would be an adolescent and travel with his father in 1778 to France and the Netherlands when his father served the American cause as a diplomat. Thus, three future presidents served in the military and three served in the political realm during the American Revolution and all their contributions aided the cause of American independence in one form or another.

Further Readings

- Andrew Jackson: His Life and Times By: H. W. Brands

- James Madison: A Life Reconsidered By: Lynne V. Cheney

- James Monroe: A Life By: Tim McGrath