As is the case with modern America, the individual colonies of colonial America had distinct characteristics among their populations that created local and regional community identities that differed from the rest of the continent. New England, being the second oldest established providence in the New World, held long ties to its Puritan roots of religious separation from England. Coupled with the reliance on merchant trading, many of the earliest communities developed along the coast to foster maritime accessibility. While this was also true for the middle and southern colonies, New England’s established trade routes and closer proximity to Europe allowed for it to be the primary destination for the majority of imported goods. This created wealth and prosperity throughout the region and explains why it became ground zero for resistance to British taxation in the 1760s.

While port cities like Boston, Gloucester, and New Haven defined the region’s main economy, it was the several rural villages that made up the backcountry and interior landscape. Most towns had more than one church, showing the diversity in religious affiliation, and a place where citizens gathered for worship, community events, and political speeches. It was not uncommon that meeting houses and churches overlapped in their ability to draw performances by local speakers. But governmental duties were strictly performed in official residences of the legislature. Cities and townships had local assemblies that represented the functioning governmental bodies. These elected officials served at the pleasure of the royal governor of the colony, who reported directly to the Court of King George III. While they could and did oversee local issues, and made legislative decisions on behalf of the citizens, they did not have a seat in Parliament. This exclusion would come to define the unfolding events leading to the American Revolution. The court systems were divided between local magistrates, royal judges, and the vice-admiralty courts which oversaw maritime disputes and issues. The latter would also serve a pivotal role in deteriorating cooperation with Boston merchants, tax collectors, and the British government.

The makeup of most New Englanders came from the British Isles and portions of the Netherlands. Because of this makeup, along with commonalities in religion, cultural practices, and intermarrying, led to a strong cohesion among the commonwealths. It also explains why so many first defended their natural rights as Englishmen, and then openly objected when these rights were being violated because they were Englishmen. For the majority of colonists, daily life consisted of supporting the profession the family was centered around. Nearly all rural communities were supported by farming while the larger, more concentrated port cities were hubs for mercantile businesses and artisan trades. Women were primarily responsible for the rearing of children at home, but many also were forced to work jobs such as cooks, washers, spinsters, and seamstresses if widowed or necessity demanded it. Others served as prostitutes and camp-followers to the colonial militia and British regulars. Though the early push for abolition did partially arise in New England, slavery was still the common practice in the colonies through the years leading to the Revolution. The streets of Boston yielded a mixture of both free and enslaved black Americans during the period. It was also common for farms and plantations (yes, they did exist in the North) to have enslaved people working them. The most tedious relationship between white colonists was that with Native Americans to their immediate west. Relations had been mixed throughout the two centuries of cohabitation, with a handful of Indian raids that left permanent stains on community memories.

At a time when the community was emerging to help identify local Americans as neighbors, townsfolk, and fellow English subjects, perhaps nothing shows this more than how they perceived themselves to be citizens of their colony. The concept of "American" as we know it today did not exist yet, and while a handful of people were forward-thinking enough to cast the term over every colonist in North America, it was far more common for people to think locally and consider themselves as citizens of Massachusetts or Connecticut. The first examples of colonists self-identifying as American would come with the 1760s protests against the British Parliament. Ironically, Londoners had long been using the term as a derogatory name for colonists — much like Yankee Doodle would later be reused by colonists to mock those British citizens doing the insulting.

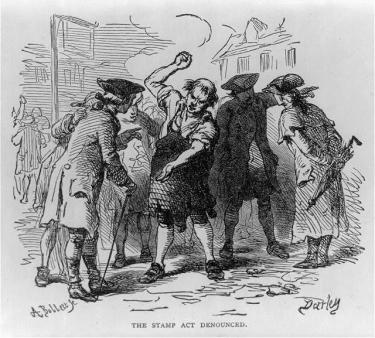

As we touched on religious affiliation within New England, we must also understand the grips of which the continent was in. The First Great Awakening, a spiritual revival that coupled with the Enlightenment, was occurring through the mid-eighteenth century and having dramatic effects on English Protestantism. Among the many changes it brought was the further acceptance of religious diversity in communities and the expansion of Christianity into new circles, particularly among black Americans. It also played into the philosophical elements taking shape that defined the new interpretations of liberty and freedom. These cornerstones, once taken root, allowed for the first movements for societal change to emerge in the 1760s. The battle over the Writs of Assistance dilemma in 1760 pitted the monarchial powers of Massachusetts governor Francis Bernard and Chief Justice Thomas Hutchinson against populist forces under the emerging oratories of James Otis and others. Before the Sugar and Stamp Acts would elevate the temperature to declarations of radical measures and violent demonstrations against British taxation, the first impulses harnessed by Otis were against British elitism, something laborers, dockhands, and merchants all felt jeopardized their interests. It was here where the very first elements of what became the American Revolution would begin. However, it would be untrue to suggest these feelings were widespread in New England. As the taxation crisis persisted, citizens were divided among economic and regional interests, with rural citizens largely retaining strict allegiance to the British monarchy. Even in port cities like Boston where the demonstrations were loudest, many citizens remained uneasy with the constant shouts for liberty and freedom. Loyalty to the British Crown remained pervasive as evidenced by how many evacuated Boston with the British army in 1776.

Further Reading

- Major Problems in the Era of the American Revolution, 1760-1791 By: Richard D. Brown

- From Puritan to Yankee: Character and Social Order in Connecticut, 1690-1765 By: Richard L. Bushman

- Religion in Colonial America By: Jon Butler

- Revolutionary America, 1750-1815: Sources and Interpretation By: Cynthia A. Kierner

- Major Problems in American Colonial History By: Karen Ordahl Kupperman

- Liberty and Authority: Early American Political Ideology, 1689-1763 By: Lawrence H. Leder

- Abraham in Arms: War and Gender in Colonial New England By: Ann M. Little

- The Social Structure of Revolutionary America By: Jackson Turner Main

- The Urban Crucible: The Northern Seaports and the Origins of the American Revolution By: Gary B. Nash

- Political Parties in Revolutionary Massachusetts By: Stephen E. Patterson