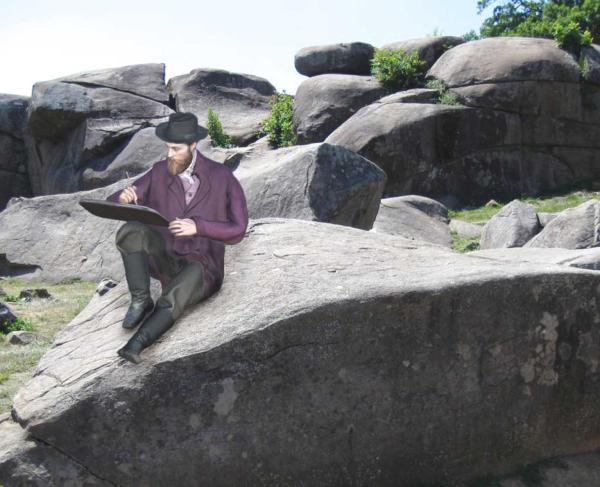

Clark “Bud” Hall at Brandy Station Battlefield, Culpeper County, Va.

When Clark “Bud” Hall was a boy, growing up the youngest of eight in Neshoba County, Mississippi, he had two goals — to be a Marine and to be an FBI agent. “I accomplished both,” he says, without a hint of hubris, but instead an endearing mix of modest determination and humble astonishment looking back at what many consider a storied life.

The truth is, he “accomplished both” and then some.

Building upon esteemed careers in the military and with the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Hall went on to help spearhead the modern battlefield preservation movement, the culmination of which is today’s American Battlefield Trust and nearly 60,000 acres of saved battlefield land, including his beloved Brandy Station Battlefield, which has now been preserved forever as part of Virginia’s newest state park.

Basic Training

An athletic teenager, Hall benefitted from the mentorship of coaches who recognized in him tenacity and leadership skills. He then joined the Marine Corps and “found the home for which I had been searching for 18 years.”

As a quiet, active and self-disciplined young Marine, Hall was, again, recognized and rewarded, moving through the ranks quicker than most. “Leadership positions were not sought, but rather earned, and promotions always came as a surprise, and a delight,” he says.

In June 1965, his unit was shipped off to Vietnam, a place, Hall admits, “We never even heard of.” The experience was heavy, rough and bitter — indescribable, really. And Hall saw many good Marines wounded and killed.

After enduring tough assignments in charge of men fighting in the jungle, many operations he would rather forget, but are impossible to, he served as security detail leader for Lt. Gen. Lewis Walt. During this assignment, Hall got to see a larger perspective of the war — the strategic. After his long service in Vietnam, he was selected as a drill instructor for new Marine recruits.

Investigative Skills

Upon returning from Vietnam, Hall attended Kansas State University and worked part-time as a deputy sherriff, setting his sights on his next role: FBI agent. In 1971, he entered the Federal Bureau of Investigation and was assigned to the Minneapolis Division, where he worked interstate theft investigations and illegal gambling businesses. In 1972, he transferred to the Milwaukee Division and joined the Organized Crime Squad, investigating Sicilian criminal activities, including illegal gambling, police corruption and mob killings.

Again, with an aptitude for the job in front of him, he served as the nationwide gangland slayings coordinator for the Bureau, and in 1977, was selected by the FBI’s Organized Crime chief to be transferred to the Las Vegas Division, where he was assigned to investigate top organized crime figures. This complex and successful investigation exposed serious police corruption in Las Vegas, as well as hidden ownership of Las Vegas casinos by Midwestern organized crime families.

His later career included being appointed as the assistant director for the Office of Special Investigations, managing congressional investigations for select committees involving intelligence and federal criminal matters. Hall was designated as chief investigator of the House Select Committee to Investigate Covert Arms Transactions with Iran. This threshold joint House and Senate inquiry examined the role of the National Security Council in providing arms to Iran in exchange for the release of U.S. hostages held there.

A Monumental Discovery

In 1984, working in Washington, D.C., and living in one of its Virginia suburbs, Hall was training for the Marine Corps Marathon when, on a trail run, he made a discovery that compelled him to new action and a new chapter of his life, one he attacked with as much gusto and perseverance as everything he had previously. Stumbling upon the neglected monuments for Union Gens. Isaac Stevens and Philip Kearny on the overgrown and disheveled fields whereupon the September 1, 1862, Battle of Ox Hill raged, Hall’s interest was piqued. The marker plot was overrun and two of the rails had fallen in.

Using his investigative skills, he soon uncovered the history of the markers, erected in 1915 to commemorate the generals on the battlefield where both had been mortally wounded during the fight. “I was immediately stunned as to why the markers were so badly neglected,” Hall says, and that “nobody cared.”

“Looking back,” he adds. “I do realize my Vietnam experience had a great deal to do with this subsequent, almost necessary involvement in battlefield preservation. Horrified by the sudden death of Marine buddies and then coming home to an uncaring public that shrugged its shoulders (and worse) over our sacrifice.… Nobody cared except for the families of those who were lost.”

Knowing the ultimate sacrifice of these two generals and observing that “nobody cared,” Hall says, “This, I could not abide, as before, and considering I was in America, on American turf, I went to work.” Trees and vines were removed from the marker plot, and the rails were re-connected and painted. Thereafter, Hall mowed the plot every Sunday morning.

“Someone finally cared, and soon our number was three,” Hall says.

When Northern Virginia development threatened to encroach the land and developers sought to move the monuments, Hall, along with fellow battlefield preservationists Ed Wenzel and Brian Pohanka, established the Chantilly Battlefield Association, widely perceived as the first Civil War battlefield preservation organization of the modern era. Hall and others soon set their sights on saving additional battlefield land, and in 1987, the Association for the Preservation of Civil War Sites was formed. It is one of the two preservation organizations that would merge to form today’s American Battlefield Trust.

The rest, as they say, is history, or at least the preservation of it.

A deep personal connection to the battlefields and the stories of the soldiers they hold compels Hall to continue the fight. “That people don’t care, I simply can’t fathom,” Hall says.

Help raise the $429,500 to save nearly 210 acres of hallowed ground in Virginia. Any contribution you are able to make will be multiplied by a factor...

Related Battles

866

433

1,300

800