A Grand Skirmish

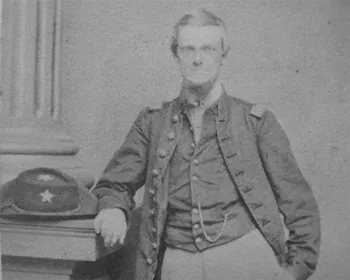

On June 14, 1864, George Stilwell of the 102nd New York writes his brother telling him of the heavy cannonading he hears that day. "[F]ights are getting to be a common thing now days," he writes, likely unaware that a Federal artillery shell has not only killed one of the Confederacy’s most popular generals but will also lead to a heavy fight for him and his comrades in Brig. Gen. John W. Geary’s "White Star" division of the Twentieth Corps.

In the first weeks of June, Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s three armies have marched toward Marietta, roughly 20 miles outside of Atlanta. Predictably, Confederate Gen. Joseph E. Johnston has erected yet another series of earthworks to block Sherman’s path. It's likey the shots Stilwell hears are directed at Pine Mountain, a salient in the center of a ten-mile defensive line that extends from Lost Mountain on the west to Brushy Mountain to the east, near Big Shanty. In addition to killing Lt. Gen. Leonidas Polk, the artillery fire on Pine Mountain convinces Johnston to abandon the position and withdraw the center of his line.

Sherman’s orders for the 15th are simple: advance. The Twenty-third Corps will advance on the Union right flank toward the Confederate position on Lost Mountain while Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson’s Army of the Tennessee moves on the left toward Big Shanty. Maj. Gen. George Thomas, commanding the the Fourth, Fourteenth, and Twentieth Corps of the Army of the Cumberland is to "break the enemy’s center," seizing the portion of the Confederate line that includes Pine Mountain, a ridge to the west of it called Pine Knob, and a crossroads just beyond a small house of worship called Gilgal Church.

Early on the 15th, men from the Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard’s Fourth Corps confirm that Johnston has indeed abandoned Pine Mountain. Accustomed to Johnston’s pattern of entrench and retreat, Sherman assumes the Confederates have withdrawn from the entire line. He is mistaken. Lt. Gen. William Hardee’s corps—including Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne’s crack division—occupies strong earthworks on Pine Knob that extend just beyond Gilgal Church, connecting with the Confederate position on Lost Mountain. A pair of batteries support Cleburne’s three brigades who, in the words of one Federal, have "bestowed a week’s labor in preparation" for the Yankee attack.

The ground here consists of "a series of steep ridges with narrow ravines in between…with frequent deviations by way of irregular spurs and small hills." It is also, according to General Geary, covered "entirely" with woods. A unified advance by Thomas’ troops is nearly impossible. Geary reports that he cannot make a connection with Howard’s troops on his left. Furthermore, he has no connection with Maj. Gen. Dan Butterfield’s division of his own corps. What was meant to be a concerted effort by Thomas’ three corps will become separate engagements fought by two isolated divisions of Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker’s corps.

Geary places his two strongest brigades, those of Col. David Ireland and Col. Charles Candy, on the right and left of his division, while Col. Patrick Jones’ brigade occupies the center. They are deployed in two lines, allowing the second to come rapidly to the aid of the first should the need arise. Four companies of the 147th Pennsylvania under Col. Ario Pardee, Jr. screen Geary’s advance.

Somewhere off to Geary’s right, Butterfield arranges his division in a much narrower formation. Brig. Gen. William Ward’s Illinois brigade leads the way, followed by Col. John Coburn’s and Col. James Wood’s. Butterfield, however, will fight more or less on his own. After a tepid effort, "Magnificent Dan" fails to capture the crossroads at Gilgal Church and calls it quits, roughly 100 yards in front of Cleburne’s works. He tells Hooker "the [Confederate] position is of such strength that I cannot carry it." He wishes that "[t]he Twenty-third Corps should be ordered forward on my right," he adds. He would also like Geary’s division to extend its front to connect with his left.

John Geary, however, is having a rough day—arguably more so than Butterfield. Advancing with the rest of the corps at 2:00pm, Geary’s vanguard makes contact with the enemy after only a short distance. Col. Pardee is convinced his skirmishers are insufficient to drive the Confederates from their rifle pits and asks for assistance. Geary orders him to hold tight; the rest of the division will be coming up for an assault.

The White Star division succeeds in clearing a ridge directly in their front. The Yankees then charge "impetuously up to the very mouths of [the enemy’s] cannon." With no connection to the units on his right or left, Geary believes he is being flanked. In fact, his men have come upon a steep angle in the Confederate works lurking in the gap between their right and Butterfield’s left. On the right of Ireland’s brigade, the 102nd New York is "temporarily thrown into disorder by an enfilading fire of the enemy," prompting two regiments from the second line rush to their aid. Col. Charles Candy’s brigade experiences a similar crisis on the left flank that is resolved in a similar fashion. Elements of Brig. Gen. Alpheus Williams’ division (advancing in support of Geary and Butterfield) also come forward to bolster the Union advance.

With his flanks secure for the moment, Geary presses "steadily and rapidly forward" up another steep ridge, toward a second line of works. The slope is strewn with slashed timber, "strong abatis, and also chevaux-de-frise of pointed stakes." As they advance, the fighting becomes "very severe" according to a captain in the 29th Ohio. Confederate artillery (Geary counts an improbable 18 pieces in his front) plays havoc with the Yankees in this sector. Geary believes his enemies know "that if [their position] were carried by us all to them would be lost."

Near the center of Geary’s line, the 60th New York is less than 100 yards from Cleburne’s works—easy killing range for rifled muskets—before dropping to the earth for cover. A slight knoll provides a bit of protection for the men, who scratch out a ragged trench with their cups and bayonets. Even after the sun goes down, the slightest move draws a volley from Cleburne’s ever-watchful troops. Later that night, Geary pulls his brigades back to a safer distance, where they entrench.

Desultory skirmishing the following morning adds to the casualty lists, but when the Yankees again advance, they discover the Confederates have once again withdrawn. While Hooker’s men toiled in front of Pine Knob and Gilgal Church, the Army of the Tennessee succeeded in flanking the Confederate right at Big Shanty, and Schofield’s men effectively turned Johnston’s left at Lost Mountain, making Cleburne’s position untenable.

For Sherman, the fighting at Pine Knob is merely one part of "a grand skirmish" in front of Johnston’s "Mountain Line." For Geary, however, it is the bloodiest engagement of the campaign. Five hundred and nineteen men of the White Star division are casualties by June 16, including a disproportionate number of officers. Butterfield’s attack, by contrast, results in the loss of just 125 Federals. The disparity in numbers supports Geary’s claim that the fighting this day was done "principally by the White Stars." Confederate reports for this period of the campaign are scant and their total number of casualties is unreported, but with the Federals failing to break Cleburne’s line and the terrain preventing the Yankees from using artillery, it is unlikely that the Confederate loss is substantial.

In the coming days, more skirmishing will drive Johnston’s army to another line of earthworks, a nearly impregnable position at Kennesaw Mountain. There, Sherman’s growing impatience will get the best of him for the last time as he launches a massive assault against Johnston’s works that ends in bloody failure.

The pall of Sherman’s lopsided repulse at Kennesaw Mountain casts a large shadow over most of the fighting in June, 1864. Pine Mountain is primarily remembered for the death of Bishop Polk on June 14—not for the role it played in the strategic picture at Marietta. Furthermore, the fact that the terms Pine Hill, Pine Mountain, and Pine Knob are used almost interchangeably in Federal reports does little to help historians adequately define the fighting on June 15 and further diminish the battle’s notoriety.

This apparent lack of import—and the site’s proximity to the City of Atlanta—have contributed to the loss of the Pine Knob battlefield. Only a small section of Cleburne’s earthworks along Due West Road is protected today, but this is more closely associated with Butterfield’s assault on Gilgal Church. Pine Knob—where the bulk of the fighting occurred on June 15—is now a suburban neighborhood. Only state historical markers tell the story of the battle that raged through what is now an idyllic family community, complete with tennis courts and spacious homes.

The Battle of Pine Knob—like so many lost battlefields—can only be experienced through imagination. The "irregular spurs" described by Geary are perfect sites for large brick houses with well-manicured lawns that belie the once-deadly character of the undulating terrain. In the woods across the street from a row of these homes, one can find the remains of the flanking trench that caused havoc on Geary’s right flank. A simple state marker describes the action here. On a nearby street, another marker points the way to the trench dug by the men of the 60th New York. Visitors can follow the trench only so far, however, before they wind up in someone’s back yard. In spite of this, visitors to the battlefield today can still get an understanding of how the uneven terrain shaped the battle and lead to John Geary’s worst day of 1864.