Green Spring

By the summer of 1781, British and American forces had tramped across the Southern Colonies, with no end of the war in sight. British forces under General Charles Lord Cornwallis had left North Carolina low on supplies after the Battle of Guilford Courthouse and proceeded north into Virginia, meeting an army under the command of Benedict Arnold outside of Petersburg. This combined British force then proceeded east towards the Virginia Peninsula in order to reach Portsmouth and open access for naval supply and reinforcement from the main British army in New York.

Cornwallis was shadowed during this movement by an American force of around 4,000 men under the command of the Marquis de Lafayette. While the British Army was composed primarily of regulars and veteran Loyalist units, the American ranks were primarily filled with Virginia Militia, with a strong corps of Continental regulars.

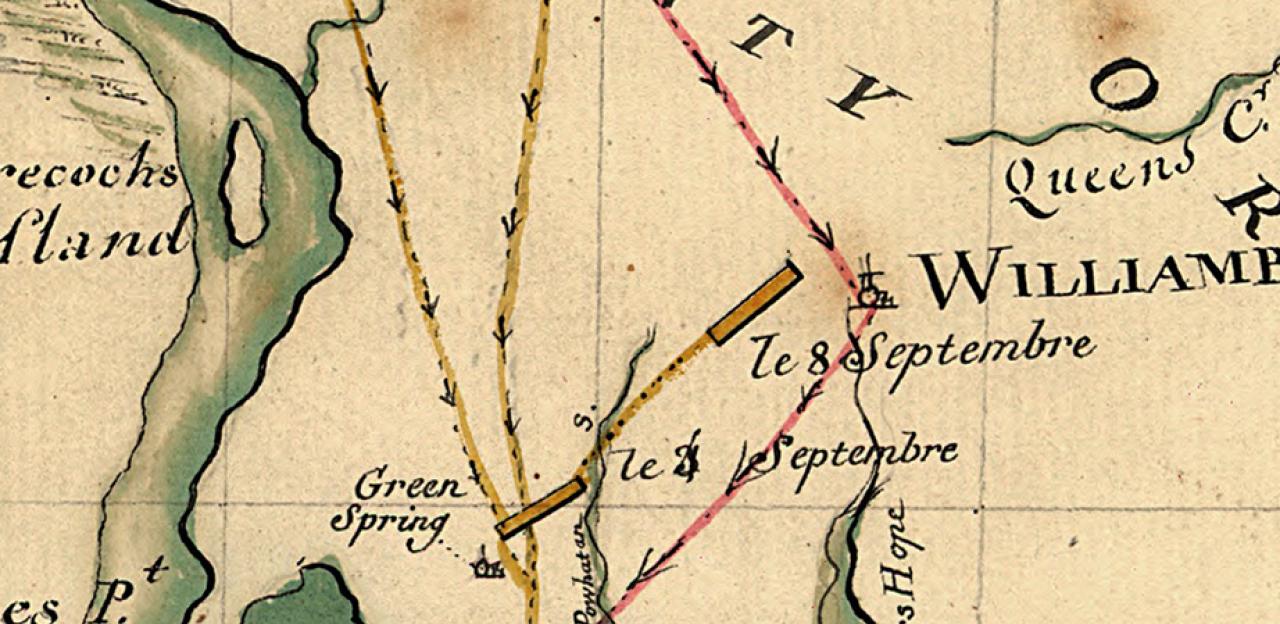

The British continued down the Peninsula, skirmishing with their pursuers, and finally reached the area of Jamestown on July 4th. Cornwallis’ plan was to cross the James River at the Jamestown Ferry and then proceed to Portsmouth. However, informed that Lafayette was closing in upon the British, Cornwallis prepared a defensive position in the area of the Green Spring, hoping to ambush the smaller Continental force and eliminate future threats to the British march.

Green Spring was named after the plantation which stood there, and was surrounded by marshy ground, dense woods, and valleys. The British positioned their regular regiments in the woods and valleys, concealed from any approaching enemy force. The British baggage train was sent to the south side of the James, along with the loyalist Queens Rangers and North Carolina Provincials.

On next day, July 5th, Lafayette’s American force reached Norrell’s Mills, only eight miles from the British crossing point. Lafayette had the men sleep upon their arms for the night, intending to move on the British first thing in the morning. The Americans believed that the British force was divided, and that Cornwallis remained on the north bank of the James with only a small portion of his army.

On the morning of July 6th, 1781, Lafayette accompanied an advance guard of 500 Pennsylvania Continentals and members of the one of the composite Light Infantry battalions, all under the command of General “Mad” Anthony Wayne. Upon reaching the area of Green Spring, the Americans began skirmishing with pickets under the command of Banastre Tarleton. Lafayette, feeling as though he had caught the rearguard of the British, called for the rest of his force to march to the battle.

As Wayne formed up, Lafayette explored the possibilities of crushing this British force on the north side of the river. As he proceeded forward, he noted large groups of men in red coats formed in lines. Cornwallis had led the Americans right into his trap.

Lafayette galloped back to the advance guard under Wayne, but it was too late. Wayne was advancing with several regiments of Pennsylvania Continentals, Light Infantry, and Virginia Riflemen. The 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Pennsylvania ran headlong into a brigade under Lt. Col. Dundas consisting of veterans troops of the 43rd Regiment of Foot, as well as the Scots of the 76th and 80th Regiments of Foot. This brigade pushed back Wayne’s men as Lt. Col. Yorke’s Light Infantry battalions pushed forward on the British right. A second line consisting of the battle hardened Guards, 23rd, and 33rd regiments of Foot was held back as a second line.

Dundas’s Brigade smashed through the American right flank in a decisive bayonet charge while the American left was being hard pressed by the British light infantry, and Lafayette gave the order for the entire American force to withdraw. Wayne, seeing both of his flanks collapsing, felt as though there was no time to withdraw his Pennsylvanians. To give the rest of the army time to withdraw, he ordered his outnumbered men to make a bayonet charge straight into the British center.

As the Pennsylvanians fixed bayonets, Wayne had his artillery fire grapeshot into the advancing Redcoats. The ensuing infantry charge temporarily stunned the British advance, as the men stopped to fire into Wayne’s men. For fifteen minutes the two sides blazed away at each other until Wayne judged the carnage too great for his men to hold out any longer and ordered a retreat. At the same time, Cornwallis led the British in a countercharge which drove Wayne’s men off of the field.

Two battalions of American Light Infantry covered the American withdrawal, with Lafayette riding among the retreating men until his horse was shot from under him. With the Americans in full retreat, Cornwallis chose not to pursue, and instead took the opportunity to safely cross his men to the south side of the James.

The Americans fell back to Richmond, in order to regroup and re-supply. Lafayette asked for Washington to send further reinforcement from the main army to replace his losses. Meanwhile, as Cornwallis received new orders to set up a permanent supply base at Yorktown.

Cornwallis marched to the port city on the north side of the peninsula, digging in and awaiting reinforcements. Seeing this movement, Lafayette wrote to Washington, asking him to seize the opportunity the British had just given them. A French fleet under the Comte de Grasse was en route from the Caribbean, and Washington gathered his forces along with the French army of the Comte de Rochambeau and proceeded south. The decisive battle of the war in the South was at hand.