You're probably thinking “Vivandière... must be French!” And, yes, the term can be traced to the French Zouave regiments in the Crimean War (1853-1856). But you might also be wondering “okay, so who were they and why do they matter?” Well, we’ve got answers!

During the Crimean War, vivandières — also referred to as “cantinieres” — travelled with regiments, selling spirits and other comforts while also tending to the sick and wounded. Only a few years later and thousands of miles away, many local militia regiments in the United States adopted the “Zouave” name, wore vivid uniforms and welcomed a "daughter of the regiment" into their ranks. This alternate moniker for vivandières arose because she was typically the young daughter or wife of an officer.

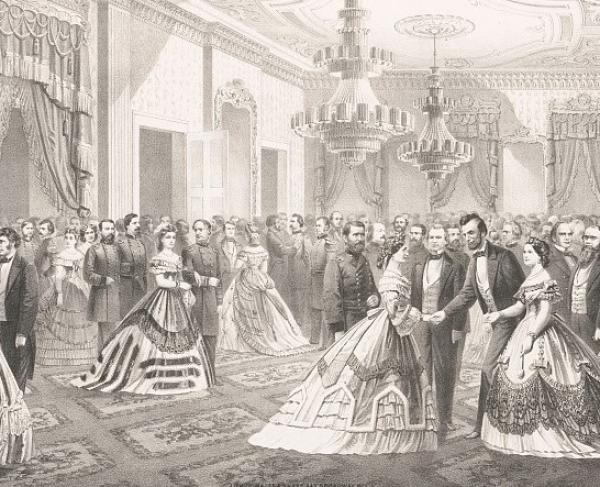

At the Civil War’s outset, Zouave regiments fought with both the Union and Confederate armies. Vivandières continued to carry libations to soldiers and were commonly seen with canteens worn on shoulder straps. Uniforms varied from regiment to regiment, but they commonly donned a knee-length skirt worn over full trousers, a tunic or jacket, and a hat, along with military trim or a designation of sorts. But don’t let their feminine skirts be mistaken as a sign of fragility!

Many vivandières proved to be fierce and determined as they tended to soldiers’ needs on the battlefield, not only through the drink carried in their canteens. While not part of the fighting force, these women charged into action when soldiers were in need of medical care, at times, weaving through the chaos of battle to tend to those dangerously wounded. It was a risk they were willing to take — many armed themselves, a few earned honors, and some even became prisoners of war. They made it their mission to make war as bearable as could be for the soldiers.

Keep reading for the stories of Marie Tepe, Annie Etheridge and Sarah Taylor — three valorous vivandières.

Marie “French Mary” Tepe

The French-born Marie Tepe followed her husband (Philadelphia tailor Bernhard Tepe) off to war in the spring of 1861. Originally with the 27th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, Marie is known for her work as vivandière of the 114th Pennsylvania. A Zouave unit organized by Capt. Charles H. T. Collis, the 114th (A.K.A. Collis' Zouaves or Zouaves D' Afrique) proudly donned the Zouave uniform — and so did Marie, with a few adjustments! With a blue jacket and red pants, she completed her vivandière look with a skirt trimmed in red.

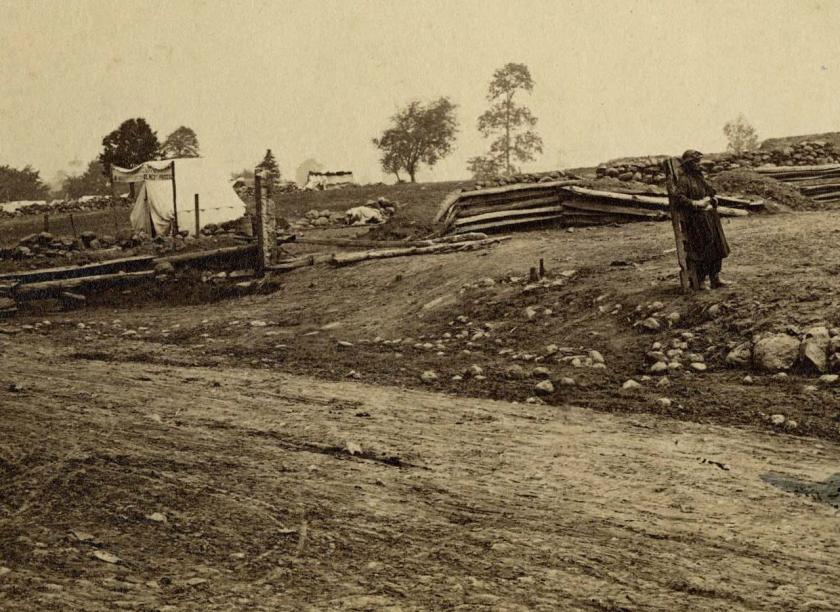

Nicknamed “French Mary” by the soldiers she aided, Marie received praise for her extraordinary efforts. During the Battle of Fredericksburg, she was right behind the battleline on the Slaughter Pen Farm — site of the largest and most complex private battlefield preservation effort in the nation’s history — when she was wounded in the ankle while delivering water to the wounded. Collis even wrote a letter thanking her for her bravery and Lt. Col. Federico Cavada gave her a silver cup inscribed, “To Marie, for noble conduct on the field of battle.”

Ever dedicated, Marie rejoined her regiment after a short hospitalization. She was present during the May 1863 fighting at Chancellorsville, where her “skirts were riddled with bullets” as she supplied soldiers on the battlefield. After, she proceeded to work at a field hospital for weeks. For her service at Chancellorsville, Marie received the Kearny Cross, a decoration given in honor of the division’s first commander, Maj. Gen. Philip Kearny.

Marie and her red, white and blue keg became legendary, and were recognized by soldiers army-wide. She joined her regiment at Gettysburg, wintered with them at Brandy Station and braved the 1864 Overland Campaign.

In August 1864, Marie left her vivandière role, and with a new husband in tow! After her first marriage collapsed, she married Corp. Richard Leonard, likely in Culpeper, Va. The two settled in Pittsburgh.

“Gentle Annie” Etheridge

When the Civil War broke out, Annie Etheridge joined in with the 2nd Michigan Volunteer Infantry as a regimental nurse alongside her soldier-husband. While he eventually deserted his post, “Gentle Annie” continued on, serving as not only a nurse but also a vivandière – in the 2nd, 3rd and 5th Michigan Infantry. With this role, she rode into the midst of battle on horseback to provide water and aid, often seen with a bullet-riddled skirt, pistols at her side and saddlebags filled with medical supplies.

She participated in 32 battles with the Army of the Potomac, including First and Second Manassas, Williamsburg, Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville and Gettysburg. At Chancellorsville, Annie had been on the front lines tending to soldiers when she was ordered to the rear. On her ride back, a musket ball grazed her hand. For this and other instances of true bravery, General David Birney awarded Annie with the Kearny Cross.

When General Ulysses Grant ordered all women out of Union army camps in 1864, Annie’s fellow soldiers demonstrated their fondness for the strong woman when they petitioned the commander to allow her to remain. Nevertheless, Annie, said her goodbye to the field and took up work with the Hospital Transport Service aboard the Knickerbocker. Her whirlwind wartime experience came to an end on July 1, 1865.

Reflecting on Annie’s impact, Color Sgt. Daniel Crotty of the 3rd Michigan wrote:

“The world never produced but very few such women, for she is along with us through storm and sunshine, in the heat of the battle caring for the wounded, and in the camp looking after the poor sick soldier, and to have a smile and a cheering word for every one who comes in her way.”

Passing on January 23, 1913, Annie is buried with veteran's honors in Arlington National Cemetery.

“Guardian Angel” Sarah Taylor

In the fall of 1861, 20-year-old teacher Sarah Taylor left behind her home in Anderson County, Tennessee, and rode all the way to Kentucky’s Camp Dick Robinson, where her stepfather had taken command of Company K of the Union’s 1st Tennessee. There, the men were enamored by her presence as the “Daughter of the Regiment.”

Sarah learned how to fire a gun and handle a sword. Journalists also made note of her uniform, describing her as wearing “a neat blue chapeau [hat], beneath which her long hair is fantastically arranged; bearing at her side a highly finished regulation sword, and silver-mounted pistols in her belt….” With skills in tow, Sarah was ready to energize the regiment when marching orders for Camp Wildcat came. It was written that she “mounted her horse and, cap in hand, galloped along the line…, cheering on the men.” Seen as a “guardian angel,” Sarah was a reassuring force amongst the troops, and moved with them wherever they went.

However, she was captured and taken prisoner on June 19, 1862, in Jacksonboro, Georgia, as a Union spy. In the Memphis Daily Appeal on July 18, 1863, it was implied that Sarah — called “Sallie” in the paper — had enticed a private (in some way or another) in Cobb’s battery (1st Kentucky Artillery, Confederate army) to steal a lieutenant’s horse and help her escape back into Kentucky. Yet, accounts of Sarah beyond this are next to impossible to find, leaving much to wonder about her fate!

Despite the spunk they brought to the field, vivandières’ service largely ended by September 1864, following Grant’s pronouncement. But their impact carried onward, reminding society of the grit and determination that women were very well capable of.