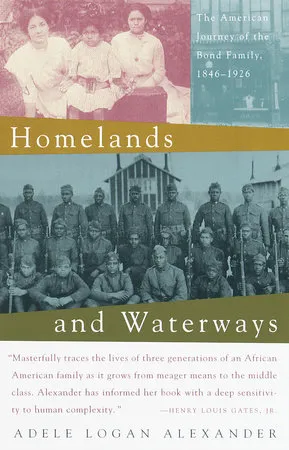

Homelands and Waterways: The American Journey of the Bond Family, 1846-1926

Homelands and Waterways: The American Journey of the Bond Family, 1846-1926 by Adele Logan Alexander is a monumental history that traces the rise of an African-American family (the author's own) from poverty to the middle class, exploding the stereotypes that have shaped and distorted our thinking about African Americans, both as slaves and in freedom.

The result of exhaustive research in academic archives and family papers, this remarkable account follows three generations of the Bond family from Victorian England to antebellum Virginia, from suburban Boston to the Jim Crow South, from black college campuses to Harvard, from naval skirmishes during the Civil War to the battlefields of Argonne. We see how, over the course of eighty crucial years in American history the Bond family both unwittingly and willfully interacted with the major political, technological, and cultural issues of their time, and how notions of race, class, and gender both limited and inspired their lives.

Adele Logan Alexander's brilliant narrative and analysis of the Bonds' journey through extraordinary adversity to their realization of the American dream is an achievement of both rich personal specificity and epic historical scope.

Adele Logan Alexander is a professor of history at George Washington University, a former board member of the Civil War Preservation Trust, and a frequent contributor to the Women's Review of Books. She is also the author of Ambiguous Lives: Free Women of Color in Rural Georgia, 1789-1879. She lives in Washington, D.C., with her husband, former Secretary of the Army, Clifford Alexander.

Homelands and Waterways features 16 pages of black-and-white photographs and is available from Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, for $30.00. Call 1-800-793-BOOK or visit the website, www.randomhouse.com.

The Civil War Trust is pleased to present four excerpts from this new gem. The first is a brief look at the battle between the USS Monitor and the CSS Virginia at Hampton Roads. The second concerns the Boston and New York City draft riots of 1863. The third looks at the 54th Massachusetts regiment and its assault on Battery Wagner. Finally, the fourth outlines a minor navy skirmish.

________________________________________

First Excerpt: Battle of the Ironclads at Hampton Roads

During the winter of 1862, the Union navy and its ground troops occupied Fortress Monroe, Hampton Roads and Newport News, while the Confederates controlled Portsmouth, Norfolk, and Hampton Roads' south shore as the Virginia was being readied to depart from the local navy yard. Spearheaded by that powerful vessel, manned by almost three hundred sailors, the Rebel armada planned to establish full command over Hampton Roads and the lower James River.

The first week of March 1862, the USS Arrago, one of many Union vessels anchored at Newport News, prepared to tackle the hazardous assignment of trying to sink the unseen, untested, but reputedly fearsome CSS Virginia. When they learned of their daunting mission however the Arrago's predominantly white crew deserted. The quartermaster in charge of contraband laborers at Fortress Monroe requested and promptly obtained seven times the number of black volunteers needed to replace the defectors. The replacements signed on as seamen, but their designated task was never fulfilled due to the next few days' unprecedented events.

On the morning of March 3, silenced crowds watched from both banks as the innovative ironside Virginia steamed slowly out of port, north along the sheltered Elizabeth River, past Craney Island, into Hampton Roads. As on many other Confederate ships, a few slaves served on board in menial positions. The massive, homely vessel rode low in the water, reminding some observers of a "half-submerged crocodile." It was clumsy and difficult to maneuver, needing an hour to negotiate a full turn, but was nonetheless a menacing presence.

It built up a head of steam, moved into attack position, then fired on the powerful USS Cumberland and the fifty-gun frigate Congress. Mauled and crippled by the Virginia's assaults, those Union ships and several smaller vessels, became "scene[s] of carnage unparalleled in the war," an observer reported. The Cumberland's decks were "covered with dead and wounded and awash with blood," and it was rammed repeatedly before plunging beneath the surface. The gory detritus of mutilated bodies, timbers, and jagged metal littered Hampton Roads' choppy waters. During those fateful hours, the apparently unstoppable Virginia caused the deaths of 250 Union seamen, wounded many more, and grounded, but did not destroy, the once mighty Minnesota. That ship included among its crew a mulatto youngster (tattooed with the figure of a woman perched atop an anchor) from New England named James Wolff, plus fourteen other Negroes manning the afterguns. "No gun in the fleet was more steady than theirs," boasted the accolades about those men's pluck and expertise. Over the course of that daunting day's exploits just off Norfolk, however, the Virginia proved itself as invincible as Confederates had hoped and Yankees feared.

The Union armada's diverse ships valiantly counterattacked the Rebel ironside. Cannon fire suffused the air with acrid smoke and a deafening clamor, but barrages from the Yankees' most powerful guns barely dented the CSS Virginia's armor. By afternoon, though its commander was grievously wounded, the Virginia had scored a remarkable success and, surrounded by sundry support vessels, stood read to dominate Hampton Roads. Following that battle, whites throughout the South applauded their acclaimed ship and laudatory messages hummed through the region's telegraph wires. In contrast, distraught accounts carried via the slaves' ever active "grapevine telegraph" rued the day.

What jubilant Confederates aboard the Virginia did not know as they anchored and retired for the evening, was that a similarly outfitted Union ship, the USS Monitor, had been dispatched from New York City. It steamed south along the Atlantic coast toward the mouth of the Chesapeake, and after dusk slipped into Hampton Roads. Though 170 feet in length, the Monitor, an awkward-looking vessel, disparagingly referred to as the "cheese box on a raft" was much smaller than the Virginia. It was equipped with comparable armor plate plus potent cannons, and was far more maneuverable than its southern counterpart.

The next morning, scarcely the hallowed Sunday it might have been, the struggle recommenced. But as the Monitor, with its Dahlgren guns blazing, emerged from behind the firmly grounded USS Minnesota, the balance of power shifted and the participation of other ships became immaterial. In the confrontation that followed, one glancing blow by the heavier Rebel vessel–by then commanded by Alabama's Commander Catesby Jones–spun its Union counterpart like a crazed gyroscope but inflicted little harm. The ironclads battled on without cease for more than four hours, "backing, filling and jockeying for position," directing thunderous cannonades at one another.

Finally, low on ammunition and hindered by the ebbing tide, the Virginia swerved slowly toward port. Both ironclads suffered trivial damage plus minimal injuries and loss of life among their crews, but survived the ordeal well. The day ended, not with a bang but a depleted whimper, as the Monitor redirected its attention toward one of its major goals--rescuing the stranded, battered Minnesota. Although the USS Monitor did not destroy or even disable the CSS Virginia in the world's first encounter between armored vessels, it cleared the way for the Union navy to control the whole mouth of the Chesapeake.

Those ships had bombarded each other and fought to a stand-off in history's most widely observed naval confrontation. Slaves and contrabands...all around Hampton Roads' periphery abandoned work in fields, homes, and shipyards and thronged shoreward to watch that terrifying yet exhilarating contest. Few had been formally educated, but they understood that the war's progress and outcome–perhaps Hampton Roads' recent brawl especially–would significantly affect their lives. "I never found one at Hampton or Monroe," wrote a correspondent from the New York World, "who did not perfectly understand the issues of the war." Negroes closely followed military developments, and for them, the battle of attrition off Newport News Point remained a memorable event. As one woman recalled, "we was all standin' on de sho' watchin'." Her mother raised her "up in her arms so dat I could see." She heard the "awful noise dem guns was makin'," and remembered that "lots of men got kilt." Another man, vividly recollecting that milestone of his earliest years, reported that "the shores was lined thick with people watching that strange fight [but] all I could see was the flash of the guns."

Although absolute maritime supremacy remained unresolved, Hampton Roads had been kept open to Yankee gunboats. Between the Union navy's enhanced efforts, the presence of the Army of the Potomac on the Hampton peninsula, plus the forces headed up from North Carolina led by the intriguingly bewhiskered General Ambrose Burnside the South's optimistic interlude was drawing to a close. Nonetheless, many Rebels, for whom averting a loss seemed almost as great an accomplishment as victory, acted as if they had won, not only the naval stalemate but the war itself.

Southerners celebrated the CSS Virginia's debatable success. One booster reported that "gratulatory words are passing from one to another as people meet in the streets...and thanksgiving is made in the churches." Though neither side definitively established its preeminence that March day, the confrontation conclusively demonstrated that steam-powered iron vessels represented the maritime face of the future, and the era of the graceful wooden sailing ships' supremacy was grinding to a close.

________________________________________

Second Excerpt: Draft Riots

On July 14, 1863...Boston's draft riot began in the largely immigrant North End when a group of angry. women assaulted two agents who had served conscription notices on several local lads. Idlers joined the fray and, armed with only fists and clubs, almost killed a constable who, tried to, restore order. The mayor mobilized militia companies and called in a contingent of United States troops garrisoned nearby. Crowds attacked the armory where they assembled, and authorities resorted to cannon fire to repulse the rioters. Protesters surged out of their neighborhood seeking weapons, but the well-armed police and soldiers soon terminated the uprising. Father James Healy, an up-and-coming priest of Irish and African heritage--and a brother of the ambitious young U.S. Navy Cutter Service officer Michael Healy--issued a timely call for order that many of the local Catholic clergy read at Sunday masses to help quell the simmering unrest. Despite the uproar Boston defused its draft protests with far less loss of life and property than did New York City that same week.

Many of that larger port's immigrant dockworkers had gone on strike for higher wages, and some employers replaced them with lower-paid black men. By 1860, the Irish had come to perceive the waterfront as their occupational preserve, and New York's Herald sarcastically declared that the stevedores "must feel enraptured at the prospects of hordes of darkeys…working for half wages and thus ousting them from employment." Adding insult to injury, as idle and irate workers viewed it, they found themselves susceptible to conscription in a war of which most of them wanted no part. Many whites considered it an effort to emancipate (and then insinuate into America's mainstream) black people, some of whom already had supplanted them on the docks. On July 13, crowds of predominantly poor, often Irish-born residents--victims of harsh nativist bigotry themselves--began gathering in curbside knots, venting their fury at the perceived injustices they suffered. The Democratic Party, representing that immigrant constituency, encouraged them. Many women shared the men's outrage at the draft law's economic discrimination, and joined in a four-day rampage of terror and destruction. Wielding clubs, throwing bricks (victims called them "Irish confetti"), even potatoes, they attacked draft offices. But blacks became the preferred targets, with "mobs chasing isolated negroes as hounds would chase a fox." They were hunted down, hanged from lampposts, battered and murdered in their ransacked residences. A white woman was beaten to death as she tried to rescue her mulatto child from cremation at the hands of the rabble, while drunken vandals incinerated the city's Colored Orphan Asylum. A few of the hoodlums reportedly even mutilated black corpses.

More than a hundred people died in New York's disturbances, and many times that number were injured. Losses from theft, arson, and property destruction mounted into the millions. Union troops straight from a costly victory at Gettysburg had to be called in to quell the savagery, Most participants went unpunished, but authorities arrested, tried, convicted, and imprisoned some of the more heinous offenders, A Negro physician swore that his people would hold the city responsible for their losses, though any municipal action or reparations, he mourned, "cannot bring back our murdered dead or remove the insults we feel."

________________________________________

Third Excerpt: The 54th Massachusetts at Battery Wagner

[Only a few days after the Boston and New York draft riots in July 1863] the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts, supported by the navy and joined by other army units, prepared to assault Battery Wagner. It was a key Confederate stronghold guarding Charleston's harbor, across from the notorious Fort Sumter. The evening prior to the battle, Harriet Tubman (an Underground Railroad leader, wartime nurse and scout who once led Union cavalrymen on a foray that freed dozens of slaves and destroyed valuable southern cotton) purportedly served Colonel Robert Gould Shaw his last supper.

According to the New York Tribune, a cynical Union general declared, "I guess we'll . . . put those damned [Negroes] from Massachusetts in the advance; we might as well get rid of them one time as another." Waves of "those damned [Negroes]" besieged the battery, but the southerners lay low. Suddenly, a cannon barrage deluged the Yankees, and, one participant observed, "a sheet of flame, followed by a running fire, like electric sparks, swept along the parapets,"' When his company's flag bearer fell, Norfolk and New Bedford's wounded Sergeant William Carney (who would become the first black soldier awarded a Congressional Medal of Honor) seized the Stars and Stripes and raised it aloft. "The old flag never touched the ground!" he cried.

In that hard-fought struggle, the rebels ultimately repulsed the onslaught and maintained control over the citadel. Bloodied, often dismembered bodies, many of them African Americans, littered the harborside combat zone. "When we came to get in de crops," Harriet Tubman mourned, "it was dead men that we reaped." Nurse Clara Barton, the "angel of the battlefield," later recalled "the scarlet flow of blood as it rolled over the black limbs beneath my hands." Though unsuccessful militarily, that Union effort, spear-headed by a new Negro regiment, at least briefly deflected many white Americans' doubts about black soldiers' courage or capabilities.

Numerous members of the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts lost their lives that July day, including its leader, Colonel Shaw. Confederates dumped Shaw's body into a pit, then heaped his dead black troops on top. The rebel commander Johnson Hagood supposedly announced; "We have buried him with his [Negroes]." Despite heavy casualties and the Yankee defeat at Battery Wagner, equal rights advocates considered the battle more an epiphany than an apocalypse. "This regiment has established its reputation as a fighting regiment," wrote Sergeant Lewis Douglass about his comrades-in-arms, not a man flinched, though it was a trying time." "I wish we had a hundred thousand colored troops," he concluded, "we would put an end to this war." In fact, before the conflict ended, twice as many backs as Douglass's proposed "hundred thousand" served with the Union forces. The avid abolitionist Angelina Grimké Weld, who soon thereafter moved to a home near the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts's training grounds, added, "I have no tears to shed over their graves, because I see that their heroism is working a great change in public opinion, forcing all...to see the sin and shame of enslaving such men."

________________________________________

Fourth Excerpt: A Navy Skirmish

At dawn on February 10, 1864, the weather was "hazy and thick," the temperature unusually mild for midwinter. Clement breezes blew three to five knots out of the northeast. The Cambridge anchored and prepared to investigate the seemingly helpless and abandoned blockade runners. Just after nine that fog-shrouded morning, Captain Spicer dispatched a detachment of men, including John Robert Bond, under the command of two junior officers. They lowered a pair of dinghies over the side and rowed through the shallows toward the beach. But as they debarked from the landing boats and started down the misty shoal preparing to board and secure the Emily, a squad of armed privateers who had secreted themselves behind the dunes opened fire. Members of the ambushed Yankee search party scrambled toward their side boats, heading for the ship to obtain reinforcements. Before they reached safety, however, a well-aimed rifle ball fired by one of the shoreside snipers hit Seaman Bond; ripping through his right upper chest and shoulder, passing near the main arteries and vital organs.

The skirmish ended quickly. Bond's shipmates rowed their fallen comrade back to the Cambridge, carrying him to the ship's infirmary for medical attention. Then they returned to the sandy island, where they managed to salvage only one puny dinghy from the stranded barks. They failed to take a single prisoner or recover any cargo. The frustrated crew destroyed the Fanny and Jeanne then sank the Emily with its once valuable, but now sodden, payload of salt, thereby closing out that infamous vessel's checkered career as an illicit slave carrier, a Union supply craft, and finally, a Confederate blockade runner of British registry. Shortly before six that evening, its mission complete and all men back on ship, the Cambridge charted a new course, stoked the engine, "weighed kedge and steered northward."

His race or foreign birth notwithstanding, a sailor in the military service of the United States had been grievously wounded. The retaliatory demolition of the Emily and the Fanny and Jeanne therefore, could have provided Bond's predominantly white, American shipmates with a solid measure of satisfaction. To some extent, their destruction of those belligerent blockade runners that mild winter afternoon may have helped to avenge the dark-skinned Englishman's injury. On the other hand, despite one significant casualty plus the competence and valor demonstrated by the intrepid sailors from the USS Cambridge, none of them, received medals or prize money for that day's dangerous exploits. As for Seaman John Robert Bond, his climactic year before the mast of an American navy ship had ended and he was able-bodied no more. He had served in battle, he briefly but clearly had "seen the elephant," and at least on that one inauspicious February day in 1864, the treacherous behemoth of war prevailed.