An Interview with Jim Percoco

The American Battlefield Trust had the opportunity to speak with Jim Percoco, a celebrated history teacher at West Springfield High School in Springfield, Virginia in 2018. This award-winning 32-year veteran has not only taught countless numbers of students at West Springfield, but he has also instilled a deeper appreciation of the American Civil War through his high-energy classes and battlefield visits.

American Battlefield Trust: Jim, you've been a teacher at West Springfield High School since 1980. Tell us about all the different teaching roles that you've had at West Springfield.

Jim Percoco: I actually was hired in 1980 not only because I could teach social studies/history, but because I had another marketable skill. I was a Certified Athletic Trainer. I always wanted to teach high school history and I needed “an in” and getting my certification to care and prevent athletic injuries opened up the door for me. So for eight years I taught during the day and in the afternoons and evenings taped ankles, slung ice bags, and attended all kinds of practices and games.

Much of my teaching career has revolved around team-teaching. I have spent many years working closely with our Special Education Department to insure that students with disabilities receive an optimum teaching and learning experience. I continue to team teach and advocate for it and for those students.

I also spent nine years team teaching a combined US History and US Literature course called, American Civilization. This was an intense Humanities approach to teaching and learning and really provided students with a good cultural understanding of the United States.

In 1991, after I had a terrific summer independent scholar experience supported with grant money from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Council for Basic Education I created the Applied History course which is a public history/museum hands-on course for seniors. It is a rigorous academic elective and demands a lot from students. After a semester in the classroom looking at themes and topics in history such as historiography, public memory, and historic preservation students complete a 100 internship at historic sites and museums in the Washington, D.C. area such as Mount Vernon, Arlington House, Ford’s Theatre, Manassas National Battlefield among many others. Thirty-seven graduates of the program have become park rangers for the National Park Service, while other have gone into Museum Education or Museum Studies. When I was a youngster I always thought I would become a National Park Service ranger, and through Applied History I have lived that quite vicariously.

You must have seen a lot of change over your 32 years of teaching. What's changed? What's remained constant?

JP: Young people have pretty much remained the same. They are wide-eyed, looking for inspiration, and open to new ideas or opportunities. That has remained pretty consistent. Their enthusiasm when channeled properly continues to pay off in dividends. That said young people today have far more distractions than students I taught at the onset of my career, much of this has been driven by technology and other societal changes.

What has also changed is the delivery of instruction. Teachers have far more tools available now to offer students a wide range of instructional activities. Primary sources are now digitized so students can complete real, primary source research without having to leave the comforts of their school and their home. Our thoughts about teaching and learning are also changing. Teaching and learning are becoming more collaborative in nature. In many ways we have moved into the “Age of Show, Don’t Tell.” The days of period long lectures are over. That said we must not toss out the baby with the bath water remembering that there remains room for the lecture in the classroom, particularly with history which as a constant is a narrative thread. You can use all kinds of cool techniques to impart information, but if there is no context provided for students to grasp then knowledge will remain static and not cohesive. You will have knowledge, but no understanding.

Another change in the last three decades plus is the more inclusive nature of history. The focus and growth of social history has demanded that we include stories in our American narrative of individuals and groups that were over looked. The role of women, people of color, and those often marginalized on the pages of history have assumed a greater role and voice in the teaching and fostering of historical understanding.

Singularly the greatest constant in the classroom is the teacher. If a teacher lacks passion, isn’t committed to becoming their own historian and scholar, and does not like being around young people then all the best practices employed will be for naught. For all of its might technology will never be able open the heart and spirit of a committed teacher. I think it remains a truth that great teachers are born they are not made.

What’s the secret to teaching history to today’s students?

JP: I think young people need to see a genuine interest on the part of the teacher for both themselves and their subject. That has been the key to my success. When I was writing my book Summers with Lincoln: Looking for the Man in the Monuments (Fordham, 2008) I not only made sure that I included my students on the pages of the books, but kept my classes updated on the progress of the book and the editorial process with my publisher. That approach provided for real world learning. My students saw me vested in the intellectual process of studying Lincoln sculpture and my willingness to share that with them that they essentially joined me on the intellectual journey.

Quirkiness has worked too, in my favor. Ringing the Tibetan bells at the beginning of each class and invoking the Spirit of History, for example, pulls students into a world unlike any other. It is off-beat, it is unique, and it works.

So, too, have devices such as using Lincoln Logs or what this year I am calling Clio’s Comments. Students record on the first day of class each week a quote and keep a running list of these quotes and who said them. These are not necessarily famous quotes, but rather quotes that impart life lessons. Lincoln, for example has numerous quotes about work ethic such as, “Work, work, work, is the main thing.” At the end of each quarter students pick one quote that connected with them and write a reflection in their journal. Lincoln said that the greatest human invention was the word giving us the ability to communicate with the dead, the absent, and the unborn. In such a strategy students enter a conversation with someone from the past. I’ll never forget one of my students, Betsy, telling me “ I never would have thought it possible that a man from the 19th century, and a President of the United States, could actually speak to me a student living in the 21st century.”

And do your students care much for the American Civil War? Is this a subject that is emphasized in your classes?

JP: It is easy in Applied History to make the Civil War a bit of a focus, because there are no state standards I am obliged to follow but those that I have established. The same cannot be said for my regular US History classes. In US History the drum beats of standards, much like those on a battlefield beating commands, guides instruction. In this atmosphere teachers and students are on a treadmill in a race to completely cover American history from the Age of Exploration to 9-11. A fierce debate in education today is coverage versus depth. In Virginia, US History is a survey course and while there are specific standards we are to cover in our instruction, we have to keep pace making sure we cover everything. So in US History the Civil War and Reconstruction may take at best a week to cover.

As to interest students pick up cues from their teachers so if a teacher has a deep interest in the Civil War or other era of history that often rubs off on the students. What I try to emphasize in my instruction is the notion that the memory of the Civil War is still contested today. How else can you explain folks getting upset over a public sculpture of Abraham Lincoln being erected in Richmond, Virginia, the controversy over the role of blacks in the Confederacy, and the place of the Confederate battle flag in American memory. Remember we are only a mere 150 years removed from this incredibly divisive and disruptive moment in American history. While students may think the Civil War was ancient history in reality it is not

Tell us about your interest in the Civil War. What are your favorite battlefields and subjects?

JP: Growing up outside of Boston my first true historical passion was the War for Independence. Relocating to Virginia 32 years ago I could not help being drawn into the vortex of Civil War history. But, as a ten year-old my Dad took me to Gettysburg, where we had the pleasure of hiring a licensed battle field guide. I still remember her name, Barbara Schutt who was the first female licensed battlefield guide. Since I have always been drawn to public monuments that visit to Gettysburg remains quite vivid as Gettysburg is a kind of Monument Mecca

I have pretty much trekked over most of the eastern battlefields and visited the battle sites in and around Atlanta and Chickamauga-Chattanooga National Military Park, but have a hankering to visit Vicksburg, Mississippi and Shiloh and Franklin, Tennessee. In high school I took a mini-elective on the Civil War and a friend of mine and I built a large diorama of Hood’s frontal assault at Franklin for a project.

As much as I enjoy going each year to Gettysburg the place where I have really felt the power of place at a Civil War battlefield is Antietam. Not having visited it before, in March 1981 I drove there one Saturday and spent the entire day there. At the end of the day I was emotionally and spiritually exhausted. Somehow I “knew”, I “felt” something awful had taken place there on September 17, 1862. I was truly haunted by the experience. I have never had that feeling at any other Civil War battlefield.

Of course having spent six years researching and writing a book on Lincoln public sculptures suggests another avenue of interest I have and that is the life and place of the 16th President in our national history and collective memory.

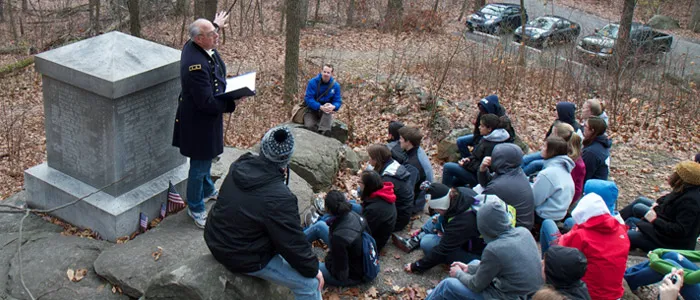

We had the good fortune of accompanying your class to the Gettysburg battlefield. Tell us about how you construct these battlefield visits.

JP: For me it is all about student engagement and getting them to interact with the space and the place. I call these trips, “academic adventures.” Getting my students as immersed in the subject as possible is one of my goals. When I first started bringing students to Gettysburg it was pretty much the standard kind of field trip experience – let’s look and see. As I continued to learn, watch some licensed battlefield guides in action, and develop my style of teaching I realized I could latch on to the power of place by doing first person readings at site specific locations, then I got the brainchild to assign students battlefield vignettes where they would become the teenage historian showing their peers what took place at specific sites, moving myself in the background. I think it is much more effective to have a student relate the sad story of Amos Humiston to their peers than for me to be the vehicle of information. There is a singular kind of ownership when a visit is constructed in such a way.

Of course context is all important, so when I bring students to Gettysburg they have more than just a cursory knowledge of July 1-3, 1863. We have been studying the battle for weeks, watching clips from Ken Burns and the film, Gettysburg. They read Margaret Creighton’s book, Colors of Courage and Thomas Desjardin’s These Honored Dead. What is so terrific about this approach is that the students are eager to “apply” their knowledge of what they already know to what they see.

One of the really interesting aspects of your Applied History classes is that you encourage your students to engage in various internships with nearby historical sites, museums, and history agencies. Why is this so important to your program?

JP: If I had not been a history teacher I probably would have become an interpretive National Park Service ranger. Growing up I learned early the importance in standing in the actual footsteps of people that have gone before us. So to be able to craft an opportunity for young people to springboard into the history profession through historical sites and museums has been very special. Since 2002 thirty-seven of the Applied History students have gone on to work as rangers in the National Park Service at various sites across the country. To know that you have played a role in this kind of personal transformation is huge. It validates what you are doing as a person and as an educational leader. It is real world stuff that is very grounded in the human experience, well beyond the invocation of “data” to prove a point. It works and works very well. I find that both humbling and inspiring.

Share with us some of the high points from your remarkable teaching career

JP: Wow! What a hard question! Certainly the fact that I have been blessed to be recognized for the work that I have done, but also to serve as an ambassador for thousands of other hard-working teachers is special. But I think what will serve as my legacy is the numbers of young people who found their calling for life through their experiences in my classroom. The American historian, journalist, and educator Henry Adams once wrote, “A teacher effects eternity, he can never tell where his influence stops.” I believe that there is a DNA connective tissue between subsequent teachers and learners that is perpetual. To be part of that process has been thrilling and to watch the fruits of one’s labor unfold in young people has been what has sustained my journey. You can’t put a price tag on that.

On a less than abstract level I would say the “coolest” experience for me was to become a talking head in the PBS film, Augustus Saint-Gaudens: Master of American Sculpture and to involve my students in the production of Paul Sanderson’s film. So much of what I am about came to its apex in that film – my love of monuments, my inspiration drawn from Saint-Gaudens work, the use and power of place to teach, the role of public memory, and establishing my credentials as a scholar. That is pretty hard to top.

During our recent visit to the Gettysburg battlefield, your students were able to use our Gettysburg Battle App. What role do you see technology playing in the education going forward?

JP: As long as there is a balanced approach to the use of technology in assisting in academic instruction we will be fine. It is one of many tools now available at our command to employ helping young people encounter and touch the past. I think teachers need to not be afraid of technology as a creative means to teach history. But we cannot let technology control us; we must be the masters of technology. Some students on our recent foray to Gettysburg felt that listening to Garry Adelman present was more powerful than the Battle Apps – he was real and available to answer questions – something a smart phone can’t do. His presence, as well as the vignettes provided by the students, kept the human element real and under no circumstances can we do away with it. Since history is a story with a narrative verve the fact that it can be dynamically presented in human form is vital. This goes back to the world of the Greeks and Romans, Homer and Virgil, they certainly did not have Battle Apps to tell the story of the Trojan War, yet what they spoke has stood the test of time and that is what really matters – the lessons that are learned, the human experiences conveyed, the dynamics that conflict provide for us to ponder and question – this is the crux of any history lesson well taught. It comes down to what works and if there is anything I have learned over 32 years of teaching is that what works for one student doesn’t necessarily mean it works for another student. Perhaps what matters most is that “they get it” no matter how that “getting it” is accomplished.

You’ve indicated that you will soon be retiring. What’s next for Jim Percoco?

JP: Hopefully a lot more of my own personal “academic adventures” will be part of my future’s mix. I have another book idea I am brewing. I feel I am at my best when I am on the road sharing my experiences with readers. That genre feels real comfortable. I’d like to think I can continue to make the world an “outdoor roving classroom.” Stay tuned!

We're on the verge of a moment that will define the future of battlefield preservation. With your help, we can save over 1,000 acres of critical Civil...

Related Battles

23,049

28,063