The state flag of North Carolina.

Emblazoned on North Carolina’s flag are two dates — May 20, 1775, and April 12, 1776 — that symbolize the Tar Heel State’s long, strong commitment to democracy and independence.

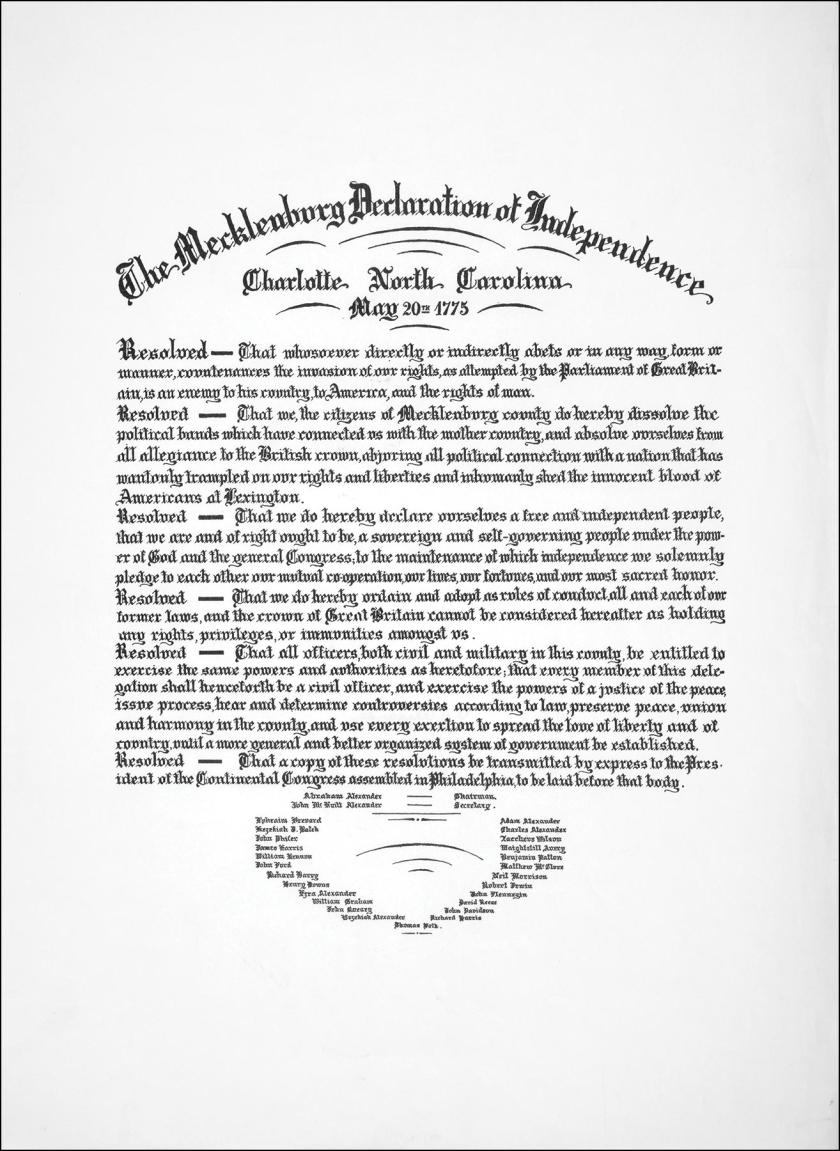

In 1819, an article published in two North Carolina newspapers reported the existence of the so-called Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence, which, if it existed, would predate the 1776 Declaration of Independence by more than a year. The article’s author, Joseph McKnitt Alexander, claimed that, on May 20, 1775, state delegates meeting in Charlotte were emboldened to write the Mecklenburg Declaration after hearing of the Battles of Lexington and Concord, with his father serving as clerk to the gathering.

Supposedly, the state delegates had dissolved their relationship with Great Britain, declaring the mother country as an enemy to not only America but also to the inalienable rights of man. Author Alexander reported that the original document, perhaps conveniently, was lost in a fire, but that supporting evidence and first-person testimonials confirmed its existence. His story went that a rider was dispatched to Philadelphia with the declaration, but he was turned away by delegates who were not yet ready for such radical action.

That the alleged document bore a startling resemblance in language to Thomas Jefferson’s more famous prose caused incredible controversy: Just how much had this secret source inspired the official one? Had Jefferson outright plagiarized it? Unsurprisingly, many prominent leaders, including Jefferson and John Adams, denounced the validity of the claim, but speculation lingered.

Proponents of the Mecklenburg Declaration crowed in the 1830s when Francis L. Hawks brought forward a 1775 proclamation by Royal Governor Josiah Martin that described an article published by the Mecklenburg committee dissolving laws and setting up a new system of government. It wasn’t until the early 1900s that it was discovered that Governor Martin referred to the Mecklenburg Resolves — a list from late May 1775 of specifically rejected British laws — not a Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence. Had the various testimonials regarding participation in a Mecklenburg-based document’s creation conflated these items? Even today, many North Carolinians choose to believe they were a year ahead of the declaration game.

The second date on the Tar Heel state’s flag, April 12, 1776, lacks such contention. Three months before 56 men signed the Declaration of Independence, in the wake of the Patriot victory at Moores Creek Bridge, the Fourth North Carolina Provincial Congress met in Halifax, North Carolina, where they unanimously adopted the Halifax Resolves. These were sent to the delegates assembled at the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia. Despite not being a direct call for independence, the Resolves ordered the North Carolina delegation in Philadelphia to form foreign alliances and vote for independence from Great Britain. With this action, North Carolina became the first colonial government to allow its delegates to advocate and vote for complete independence.