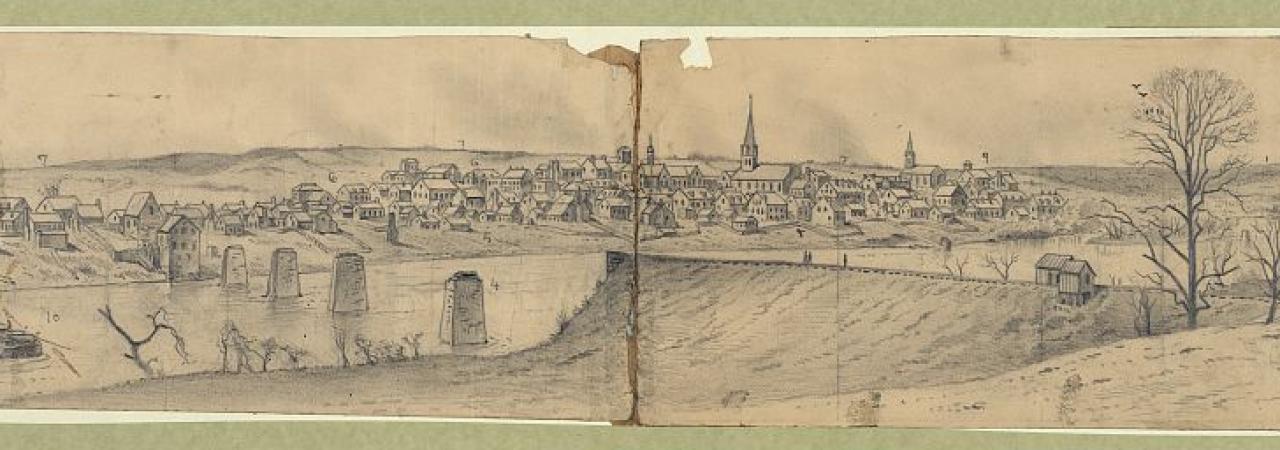

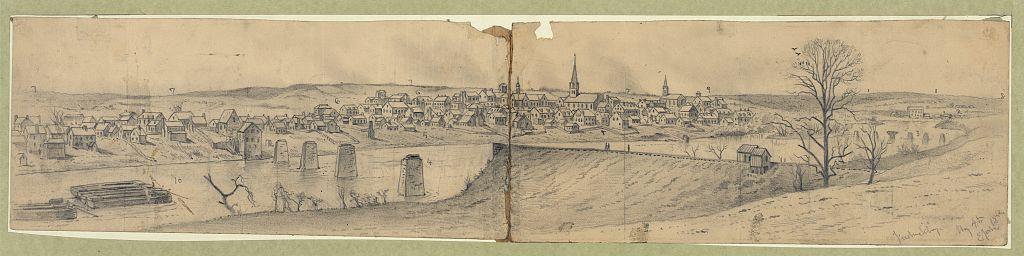

Civil War Fredericksburg, sketched by Edwin Forbes, May 1862.

On April 18, 1862, John Washington took advantage of his opportunity, crossed the Rappahannock River, and found freedom within Federal lines. For years, he had been preparing for his freedom. A very light-skinned, urban enslaved man, John Washington had earned money, traveled, knew the banks of the Virginian river, and grown-up surrounded by relatives—both black and white. After his escape from slavery to freedom, Washington wrote the narrative of his life.

John Washington was born into slavery on May 20, 1838, in Fredericksburg, Virginia. His mother was Sarah Tucker, an enslaved woman, and his father was a white man. His mother was described as a “bright mulatto,” meaning that she had mixed blood. John later described himself: “I see myself as a small light haired boy, (very often passing easily for a white boy).” Some people must have known his father’s identity since John came of age surrounded by “both white and black relatives.” Lighter-skinned slaves occasionally benefited from economic and social advantages, especially in cities and towns.

John inherited a history of defiance and freedom from his mother and grandmother. His grandmother, Molly, had been whipped for misbehaving; perhaps she had run away after her sister was sold. John’s mother, Sarah, ran away when John was three, but she returned.

Sarah knew how to read and write, uncommon skills for an enslaved woman. When her son turned four, she began teaching John how to spell and kept him at his lessons for a couple of hours a night. Later she taught him to read. John’s white relatives and friends helped him read, too. His Uncle John, who taught him to write, had to be extremely careful because it was illegal to educate enslaved people.

John spent several of his childhood years on the Brown farm in Orange County. He had pleasant memories of playing with mostly white children, wading in the brooks, and going to the circus. At ten, he moved back to Fredericksburg and lived as a servant to Mrs. Taliaferro. Back in the city, urban slavery gave him more freedom than rural slavery. Some Southern whites thought urban slavery corrupted slaves, attracting them to the “worst habits.” Free blacks said that they had merely “acquired town habits.”

John was, on the surface, both black and white, both slave and free. He probably possessed a higher degree of freedom than he admits in his narrative. He entered stores, did financial transactions for his mistress, attended Mrs. Taliaferro’s Baptist church, and talked among his friends both black and white. Some Sundays, he escaped church service and went to the riverfront with his friends to swim and row any boat that they could find. However, before doing this he would hang around the church door and memorize the preacher’s text. John developed a great love for the river and boats, and in 1852 during one of these adventures, he got a case of poison oak. Mrs. Taliaferro sent him to his mother in Staunton, Virginia so she could nurse him back to health. In 1859, John’s mother and siblings were hired away, and at that time, John promised himself that if he ever got the opportunity he would run away.

As he grew older, John’s employers and enslavers restricted his movements, fearing he would try to escape. However, they still allowed him to attend church fairs and revivals. He was baptized in the Rappahannock River on June 13, 1856. Through the years, he learned to hone his negotiation skills with his mistress and other whites. John came of age as a slave—but with his eyes on a way out of slavery. He also met Annie Gordon, whom he married on January 3, 1862.

Washington’s literacy, his connection to free blacks, his work ethic, and his urban environment all contributed to his escape. Between 1859 and 1862, he was hired out several times, during which he learned skills and earned cash for himself. He worked at the Alexander and Gibbs tobacco factory in Fredericksburg, a tavern in Richmond, and finally the Shakespeare Hotel in Fredericksburg. The tobacco company helped him gain a sense of adult autonomy through work and measured labor. At the Shakespeare Hotel, he held the position of barkeeper and steward. He must have been a trusted employee, since the owners wanted him to go to North Carolina with one of them as the Yankees approached in April of 1862.

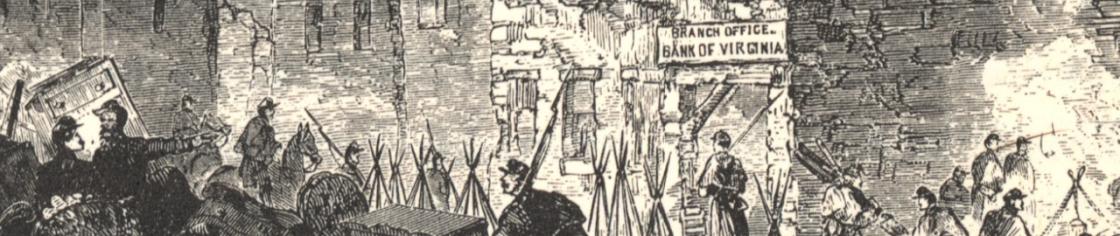

As the Union army moved into Fredericksburg on April 18, the owners of the hotel prepared to leave town. They gave John “a roll of banknotes” to pay off all of the servants along with the keys to the hotel to put into a safe place. John admits these men treated him well, but he resolved not to go with them, although he made them believe that he would remain loyal. He also told Mrs. Taliaferro that he would join her on her flight to the countryside. He acted as if he feared the Union soldiers.

While the whites in the streets of Fredericksburg moved southward, the blacks looked across the river at the Yankees. After leaving the hotel, John, his cousin James Washington, and another free colored man walked to Ficklen’s Bridgewater Mill, then to the Rappahannock River. There, they saw Union soldiers who asked them if they wanted to cross over. John shouted, “Yes, I want to come over.” And so, John crossed.

Union officials asked John all manner of questions about the Confederate army. Prepared, John honestly answered their questions. John had stuffed his pockets with rebel Southern newspapers, which he distributed to the Union soldiers.

Most of the Union soldiers thought John was a white man and were astonished to learn that he was a “colored man and a slave all his life.” They asked if he wanted to be free, and he replied by all means. His first night of freedom coincided with the religious day of Good Friday—indeed, the best Friday he had ever seen. John declared himself a slave no more!

John served the Union army as a mess servant, hostler, and general camp aide for Major General Rufus King for a period between April and August 1862. During his time with the army, he returned to Fredericksburg to identify the important people of the city and several were taken prisoner. He also got to experience some warfare, since he traveled with the army when they skirmished with Jackson’s army in the Culpeper to Warrenton areas of Virginia. He then moved to Washington, D.C. to live, and some of John’s family arrived with him in Washington. His wife Annie gave birth to his first born son, William, on October 6, 1862. He omitted in his narrative how they made it through war torn Virginia to join him. His mother and other relatives later moved to be with him in Washington.

For many enslaved individuals, the arrival of Union armies offered a chance for freedom and the opportunity to begin a new life. John Washington took that chance and created a home in freedom for himself and his family.

Further Reading

- John Washington's Civil War: A Slave Narrative By: John Washington

- A Slave No More By: David W. Blight

To restore land and history at Gettysburg, Cold Harbor, Slaughter Pen Farm and New Market Heights, we must raise $131,000. Please help to finish the...

Related Battles

12,500

6,000