Kings Mountain

South Carolina | Oct 7, 1780

The Revolutionary War battle of Kings Mountain in South Carolina proved to be a stinging defeat in the British attempt to secure control of the Southern colonies.

How it ended

American victory. The fierce firefight at Kings Mountain pitted Loyalist militia elements under the command of British major Patrick Ferguson against 900 patriots. The British effort to secure Loyalist support in the South was a failure. Thomas Jefferson called the battle "The turn of the tide of success."

In context

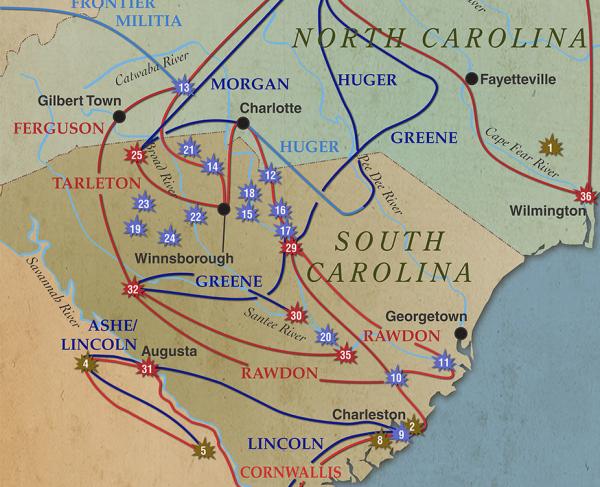

The siege of Charleston in May 1780 was one of the worst American defeats of the Revolutionary War. Another British victory, in the Battle of Camden, followed in August 1780. British general Charles Lord Cornwallis dispatched Major Patrick Ferguson to North Carolina in early September 1780. Ferguson had two tasks: recruit members to fight for the Loyalist militia and protect the Cornwallis’s left flank as he attempted to move through the Carolinas.

Nicknamed Bull Dog by his men, Ferguson soon came up against the Overmountain men, residents of the Carolina Backcountry and the Appalachian mountain range, and from places that would later become the states of Tennessee and Kentucky. American cavalry commander “Light Horse” Harry Lee called them, “A race of hardy men who were familiar with the use of the horse and the rifle, stout, active, patient under privation, and brave.” To the British, however, they were “more savage than the Indians.” From the start Ferguson miscalculated his potential foes, brazenly issuing a proclamation for the local patriots to “desist from their opposition to British arms” or he would “march over the mountains, hang their leaders, and lay their country to waste with fire and sword.” His scare tactics backfired.

On October 7, 1780, Ferguson and the Overmountain men met in a small but significant battle in the War for Independence. It took place on a rocky hilltop in Western South Carolina called Kings Mountain. The rout of the Loyalists there was the first major setback for Britain's southern strategy and started a chain of events that culminated in Cornwallis's surrender at Yorktown.

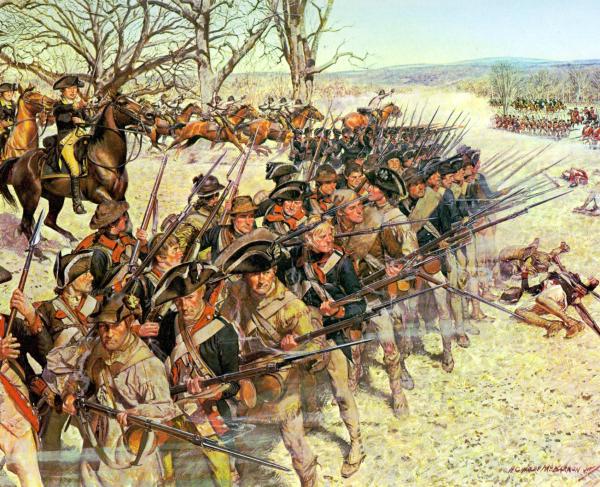

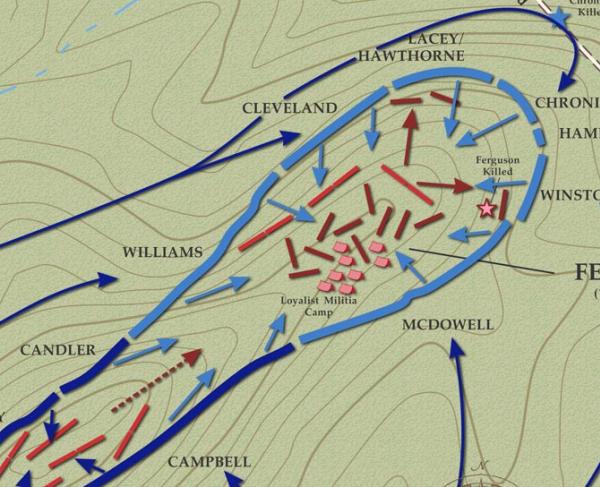

Several local patriot militias of the region led by William Campbell, John Sevier, Joseph McDowell, William Hill, Edward Lacy, Benjamin Cleveland, Joseph Winston, William Chronicle and Isaac Shelby decide to take on Ferguson and his men. Learning of their plans, Ferguson opts to retreat from his forward position and pulls back closer to the main body of the British Army. He digs in and fortifies a small 60-foot hill two miles inside the South Carolina border. An American scouting party learns of Ferguson’s position, giving militia commanders the intelligence they need to launch an attack. Sensing an impending battle, the American commanders tell their men, “Don’t wait for the word of command. Let each one of you be your own officer and do the very best you can.” The American plan was simple—to assault the hill from all sides. Campbell tells his men to “shout like Hell and fight like devils.”

910

1,125

October 7. In the early afternoon, the Overmountain men creep quietly toward Ferguson’s position. When the first shot rings out the Americans attack en masse from all sides. Ferguson deploys his Loyalist militia in the center of the hilltop. He remains mounted and personally leads the counterattack against the patriots surging from the southwest. After firing a volley and fixing bayonets, Ferguson’s men blunt the Overmountain men’s advance. But it is only on one side of the hill and the Overmountain men continue unabated to attack from the other sides using the undergrowth and woods to their advantage. One Loyalist later recalled that the Overmountain men looked “like devils from the infernal regions… tall, raw-boned, sinewy with long matted hair.” Ferguson and his men are surrounded, and their additional counterattacks fail to stop the Americans. The Overmountain men continue their yelling and whooping as they gain ground.

With his defensive perimeter shrinking, Ferguson tries to lead his men past the onslaught. Mounted on his horse, he proves the perfect target for his crack shot opponents. He is hit multiple times, his body hanging from his horse as his mount flees down the hill.

Shortly after Ferguson’s death, the Loyalists surrender.

90

1,018

The American riflemen are victorious but there is a cost. One young Overmountain man later recalled, “The dead lay in heaps on all sides, while the groans of the wounded were heard in every direction. I could not help turning away from the scene before me, with horror, and though exalting in the victory, could not refrain from shedding tears.”

At Kings Mountain the Backcountry militiamen demonstrate that they can coordinate and execute a battle plan. Their success encourages other patriot revolutionaries. General George Washington later proclaims to his own army that “The crude, spirited, hardy determined volunteers who crossed the mountains served as proof of the spirit and resources of the country.” Loyalist elements in North Carolina and South Carolina are intimidated. Kings Mountain sets the scene for an American military resurgence. With the loss of his western flank force, Cornwallis falls back into South Carolina, delaying his planned invasion of North Carolina.

The Battle of Kings Mountain was one of the few major battles of the Revolutionary War waged entirely between fellow countrymen. It was fought entirely between Americans—no British troops served there. Major Patrick Ferguson, commander of the Loyalist force, was the only Briton on the field.

As is other parts of the colonies, the South was divided in its loyalties to England. Some fought for independence, others defended the Crown. There were many reasons for people to remain loyal to the government of King George. Some of the Loyalists expected to be rewarded at the end of the war. Others wanted to protect their vast amounts of property. Many were professionals, such as clergymen (who were dependent on the Church of England for their livelihood), lawyers, doctors, and teachers. Among the Loyalists were also servants and slaves, who believed the way to freedom was not through American independence.

As a British officer, Patrick Ferguson had the burden of turning South Carolina Loyalists into a trained militia. But his hope of molding them into an effective fighting force died with him at Kings Mountain. The British ultimately failed to prepare and lead the South Carolina Loyalists to develop consistently reliable fighting units across the state and secure the area from the better-organized and drilled militias of the patriots.

The weapons of the Patriot riflemen at Kings Mountain were more accurate than those of their opponents and led to more enemy fatalities. Generally, rifles were not used by armies. A rifle was primarily a hunting weapon for families living on the frontier. But the Overmountain men at Kings Mountain mainly favored their rifles, while the Loyalist troops carried muskets.

The difference between a rifle and a musket is speed versus accuracy. A rifle is slow to load, but very accurate. Riflemen can hit a target at 200 or 300 yards. Yet the rifle can only be fired once a minute. A musket, with a smooth bore, is easy to load but inaccurate. Muskets have an accurate range of about 100 yards but can be fired up to three times a minute.

In addition to using different weapons, the opposing troops at Kings Mountain had disparate strategies. Each militiaman on Kings Mountain had been instructed to act as his own captain and to take every advantage that was presented. The Patriots fought frontier-style from behind trees and rocks. They selected a definite human target for every ball fired. The Loyalists fought in close-order ranks with volley fire and bayonet charges. Better communication and knowledge of the terrain by militia officers, combined with the skilled marksmanship of their men, trumped all the military training and discipline Ferguson imparted to his Loyalist troops.

The effectiveness of the American rifle and the skill of American riflemen made a great impression on British military leaders during the Revolutionary War and had a significant negative impact on British morale. Colonel George Hanger, a British officer in South Carolina, observed:

I never in my life saw better rifles (or men who shot better) than those made in America; they are chiefly made in Lancaster, and two or three neighboring towns in that vicinity, in Pennsylvania. …I am not going to relate any thing respecting the American war; but to mention one instance, as a proof of most excellent skill of an American rifleman. If any man shew me an instance of better shooting, I will stand corrected.

The astounded Hanger later estimated the distance between the riflemen and the horse to be a “full four hundred yards.”

Kings Mountain: Featured Resources

All battles of the Southern Theater 1780 - 1783 Campaign

Related Battles

910

1,125

90

1,018