Created separately and with different purpose from the vast nature preserves of the West, America’s battlefield parks took a long, often circuitous route to full integration into the National Park System.

Today, most Americans with an interest in the Civil War, or other eras of military history, view major battlefields and the National Park Service (NPS) as synonymous. And well they should, because NPS does indeed directly oversee America’s most revered battlegrounds. It is natural to formulate a hierarchy of battlefields and their importance, ranging upward from locally preserved city and county parks to those listed as national historic landmarks or patrolled by rangers in green and gray. While an argument could be made that some state, or even local, parks are actually worthy of federal recognition, it is commonly recognized that the cream of the battlefield crop — in terms of both historic significance and modern management — resides in the National Park Service.

Despite numerous calls for it over the agency’s early years, the transfer of battlefield parks into the National Park Service did not occur until 1933. NPS officials Stephen Mather and Horace Albright had long argued for the change, explaining that while the War Department was doing a good job at the time, the National Park Service was the government agency that had expertise in park management and interpretation. These arguments fell on willing ears, as government officials in the 1920s and 1930s realized a changing clientele was now visiting these battlefields, one that was no longer made up primarily of veterans or military officers. A more mobile civilian American public was now visiting these historic sites, and these individuals needed a different kind of experience than that provided by the War Department.

There was also, however, a more selfish reason why Mather and Albright pushed for the transfer. The National Park Service was, in the 1920s and early 1930s, nowhere near the highly recognizable governmental agency we think of today. In fact, it was a fairly insignificant and minor agency struggling for money and limelight. While the National Park Service did oversee some pre-colonial historic sites established mainly under the authority of the Antiquities Act, which itself predated the National Park Service by 10 years, the NPS was primarily a nature-centric agency. Mather and Albright realized the devotion and reverence Americans had for the great battlefields of the Civil War and knew that, if the National Park Service could obtain possession of the battlefields, it would not only push the bureau into the historic side of preservation and interpretation, but also raise the stature of the entire agency.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt was receptive to the idea, especially after a Sunday ride out into Virginia, when he found himself seated with National Park Service director Horace Albright, who brought up the idea. That Department of the Interior officials were supportive was one thing, but War Department leaders were also pushing the idea, and that sealed the action. Military officials realized recreational governance of past battlefields was not exactly in line with their critical duties, meaning the parks became further and further buried in the bureaucracy of the War Department, as no one in the military seemed to want them. A consensus reached, Roosevelt issued the necessary executive order during the summer of 1933; with the stroke of his pen, 10 major battlefields and numerous other smaller sites resided within the National Park Service.

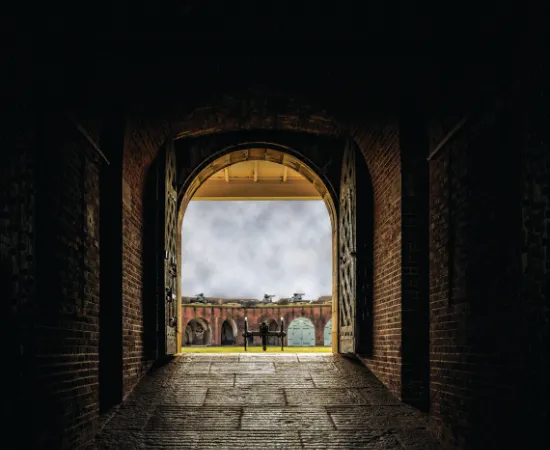

It was a steep learning curve for the Park Service to interpret and educate about historic events, but the agency swiftly set up a historic section to oversee the battlefields. NPS soon had the sites revamped (with the aid of numerous New Deal dollars and workers through programs like the Civilian Conservation Corps) and ready for the new breed of battlefield visitors. And over the ensuing decades, many more major battlefields — Saratoga, Richmond, Fort Sumter, Harpers Ferry, Lexington and Concord, Pea Ridge and Wilson’s Creek, among others — were also added to the “cannonball circuit.” After a major downturn in preservation activity in the fiscally conservative 1970s and 1980s, more new federal parks have begun to appear as well, such as those at Glorietta Pass and Cedar Creek.