Let it Rain Militia: The Critical Battle for the Chesapeake

More than three decades since the Treaty of Paris ended the Revolutionary War and 25 years since the U.S. Constitution was signed, the nation was still without a strong central government. Questions remained about trade, economy and the unresolved issue of slavery. No less important were the calls for “Free Trade and Sailors’ Rights” by the merchant seafarers and the push of the young war-hawk Republicans for westward expansion. These and other issues came to a head in the spring of 1812, as Americans debated the possibility of a second war with Great Britain. Hot button topics included England’s impressment of sailors and a desired final solution to securing the Northwest Territory, left unresolved in the 1783 Treaty of Paris.

On June 18, 1812, with America no longer able to protect its maritime neutrality amidst the Napoleonic Wars, a declaration of war was enacted to preserve and protect America’s global trade. Within months, President James Madison’s military call of “Onward to Canada” along the frontier ended in failure, due to poor leadership, lack of support from New England, poor equipage and lack of preparation. But the American invasion was not without success: In April 1813, Americans captured the Canadian capital city of York, burning much of the city and raising the American colors over Government House. Meanwhile, Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry’s signal victory over a superior British squadron on Lake Erie in September 1813 and other victories proved American naval strength and discipline.

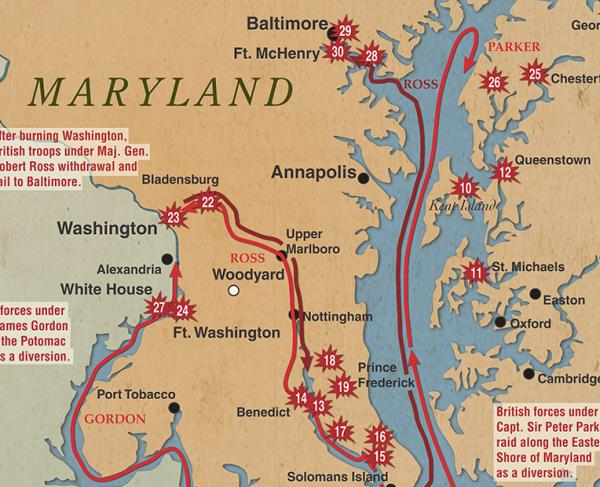

England’s war strategy for 1814 drifted southward from the Canadian frontier to the Chesapeake Bay region. America’s largest estuary was the nation’s heart of farming, commerce, ship-building and government, making it a high prize of war. In March 1814, a British squadron arrived to enforce the admiralty’s blockade declaration of the Chesapeake and Delaware Bays, making use of extensive surveys conducted of those waterways by the Royal Navy during the Revolutionary War.

On April 28, 1814, British Vice Admiral Alexander Cochrane directed Rear Admiral Cockburn to begin a devastating naval attack on the Chesapeake.

“Their Sea Port Towns laid in Ashes & the Country wasted will be some sort of a retaliation for their savage Conduct in Canada [at York].... [I]t is ... therefore but just, that Retaliation shall be made near to the Seat of their Government from whence those Orders emanated, you may depend upon my most cordial Support in whatever you may undertake against the Enemy.” The offensive was driven by more than vengeance. The global geopolitical game had fundamentally changed. Following his disastrous 1812 Russian campaign and resounding loss at the October 1813 Battle of Leipzig, Napoleon had surrendered in Paris to the allied coalition on March 31, a capitulation so complete that the emperor was forced into exile on the isle of Elba. England found itself able to focus upon a final campaign with renewed strength to chastise the Americans into submission once and for all.

Change was palpable to the Americans as well. Former Maryland Congressman Joseph H. Nicholson wrote to U.S. Naval Secretary William Jones, “We should have to fight hereafter, not for free trade and sailor’s rights,’ not for the conquest of the Canadas, but for our national existence.”

Cross-hairs on the Chesapeake

In the summer of 1814, after 18 months of British occupation and raids against port towns, the British campaign against the American mid-Atlantic was building to a climax, with Baltimore in the cross-hairs. “The Clouds of war gather Fast and Heavy in the East,” wrote American Marine Captain George Stiles that July, “and all Hands are called.”

A large invasion fleet had been reported moving north from the British naval base at Bermuda to Lynnhaven Bay, the entrance to the Chesapeake. They were able to resupply at the fortified British base on Tangier Island, Virginia, from which Vice-Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane sought to entice runaway enslaved persons to form a Corps of Colonial Marines, with the promise of freedom in Canada at the conclusion of their service.

On August 19, 1814, British land and sea forces landed at Benedict, Maryland, and swiftly forced the destruction of the U.S. Chesapeake Flotilla on the Upper Patuxent River. The primary objective — destruction of this elusive flotilla of gunboats — met, Major General Robert Ross and Rear Admiral George Cockburn extended their goals. The British routed the ill-prepared American army under Brigadier General William H. Winder at Bladensburg, Maryland, on August 24, entered the nation’s capital and burned many key buildings. The conflagration’s fiery glow was seen 50 miles to the north by Baltimore citizens who gathered atop Federal Hill and steeled themselves for the inevitable invasion.

On the evening of the August 25, amidst a severe summer thunderstorm, the British withdrew from Washington and retraced their march to Benedict, arriving on the 28th, then continued on to their naval base on Tangier Island, Virginia. to regroup, take on fresh water and care for their wounded.

Meanwhile, Captain Sir Peter Parker and his HM Menelaus had been dispatched from the main British force to raid along the northern and western shores of Chesapeake Bay, especially Kent County, Maryland. His aim was to drawing American troops away from the primary objectives around Washington and Baltimore, meaning, as British Midshipman Frederick Chamier later wrote, “Our duty consisted in an eternal annoyance of the enemy, and therefore night and day we were employed in offensive operations.”

Among the goods and supplies captured by a raiding party on the evening of August 30, Parker found himself receiving intelligence from four slaves liberated from a nearby plantation. Warned of American militia nearby, Parker was so eager for action he did not even await daylight to dispatch a force of soldiers and Marines against them. Shortly before midnight, the 21st Regiment American Militia caught sight of the raiding party and determined themselves to be the target, rather than another nearby farm. Fighting began around 1:00 a.m., and, although there was a full moon, the Americans — whose commander Lieutenant Colonel Philip Reed, a Revolutionary War field officer and former U.S. senator whose home was nearby and who had served as county sheriff — had the advantage of knowing the land. Amidst the fighting, Parker took a wound to the thigh and perished on the field, the bullet having severed his femoral artery. Although elements of the British force had made it as far as the American camp, even seizing a cannon, the loss of their leader prompted a retreat back to the ship.

Baltimore: Middle Ground of the Chesapeake

Modern Baltimore can trace its earliest origins to 17th-century English proprietary land grants to Maryland’s oldest planter-class families. The County of Baltimore was erected by 1659, and what became the city was settled in 1661. A key geographic feature of the location is the mouth of the Patapsco River, which forms the strong harbor for which Baltimore is known. The word Patapsco, meaning “back water,” is derived from the Algonquian woodland culture of the region. The area around the river made for a flourishing hunting, fishing and market-farm culture, with tidal creeks creating a marsh patchwork between farms of corn, rye and fruit orchards. Thanks to woodlands of white oak and pine, a flourishing shipbuilding economy emerged, making Baltimore a major eco-nomic center.

By 1810, the city had developed into a major and prosperous international seaport, with a population of slightly less than 50,000 — one-fifth of whom were black, including many free blacks employed as caulkers and carpenters in the Fell’s Point shipyards of Kemp, Despeaux and Price. Other Baltimoreans signed aboard privateers granted Letters-of-Marque & Reprisal to prey on and engage English merchantmen. The attacks were so numerous that London’s Evening Star opined: “The American navy must be annihilated — her arsenals and dockyards must be consumed; and the turbulent inhabitants of Baltimore must be tamed with the weapons which shook the wooden turrets of Copenhagen…. America must be BEATEN INTO SUBMISSION.”

During the spring and summer of 1814, the British war efforts in North America took on a new life. The first defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte in Europe...

Tightening the Noose

Following the American debacle at Bladensburg, American Brigadier General William Henry Winder was replaced with Major General Samuel Smith, a U.S. senator and successful shipping merchant. Although the native Baltimore Brigade had suffered losses at Bladensburg, the city turned overnight into a huge military camp — more than 25,000 militia encamped within a 10-mile radius. It was the largest gathering of militia to defend an American port since minutemen flocked to Boston in 1775, exceeding the forces gathered at Long Island, Charleston or Savannah later in the Revolution.

Merchant and citizen-soldier George Douglas wrote to a friend: “Every American heart is bursting with shame and indignation at the catastrophe [at Washington]… All hearts and hands have cordially united to the common cause.… Bodies of troops are marching in…. The whole of the hills and rising grounds to the eastward of the city are covered with horse-foot and artillery exercises and training from morning until night.”

Baltimore Mayor Edward Johnston organized a Committee of Vigilance & Safety to coordinate defense preparations. For a year, the city had been stockpiling enormous supplies of tents, blankets, canteens, muskets, cartridge boxes, camp kettles, medical supplies and other essential equipage to meet the needs of the hourly arriving independent volunteers. Four thousand Pennsylvania militia arrived with such company names as the Brownsville Blues, York and Marietta Volunteers. From western Maryland came the Hagerstown Homespun Volunteers, Jefferson Blues and Washington Rifle Green, plus more companies from western Virginia. No less than 400 independent companies responded to Baltimore’s defense.

From their camps centered around Hampstead Hill, volunteer units made up of old and young, black and white, free men and enslaved immediately engaged in digging a five-mile entrenchment around the city, bolstered by artillery redoubts. A mile behind this defensive line, U.S. Corps of Engineers Captain Samuel Babcock superintended “a last stand” fortification within the large, rising granite walls of the nation’s first Catholic cathedral in the city’s center. If the American lines failed from the expected British land assault, this would be the last bastion of defense.

From a naval assault, the city was defended by Fort McHenry. Within the star-bastioned fort — named in 1797 for then Secretary of War Colonel James McHenry — Major George Armistead (1780–1818) commanded 1,000 soldiers, militia and sailors with 60 cannon to protect the harbor entrance to Baltimore. In addition, U.S. naval gunboats blocked the entrance behind sunken merchant vessels and a chain-mast boom, all creating a crucial front line of defenses. Also arriving were a thousand sailors and 170 Marines from various independent naval commands, and a makeshift naval regiment under command of Commodore John Rodgers with his 450 sailors and 50 U.S. Marines from the Delaware River defenses. Attached to this command upon its September 9 arrival was Commodore Joshua Barney’s U.S. Chesapeake Flotilla, which, with the District Marines, had made a heroic last stand at Bladensburg, giving a much-needed morale boost to the city.

Sails on the Horizon

At dawn on September 10, cavalry Major William Barney patrolled the catwalk of the State House dome in Annapolis, eyes on the Bay to watch for British naval movements. As early light broke through the morning mist, he glimpsed the vanguard of 50 British warships sailing north under a light wind. After 19 months of tidewater occupation, the British were making for Baltimore. Four admirals accompanied the fleet — Vice-Admiral Alexander I. F. Cochrane, who conveyed Admiralty orders; Rear Admiral George Cockburn, who administered the naval deployment; Rear Admiral Pulteney Malcolm, who conveyed the troop ships to the Chesapeake; and Rear Admiral Edward Codrington, Captain of the Fleet, who administered the expedition’s conveyance and maintenance in the Chesapeake. Once ashore Major General Robert Ross, R.A., had overall command of the land forces (seamen and Marines) under advice of Admiral Cockburn, who accompanied the land forces.

Around noon on Sunday, September 11, as the British fleet appeared off North Point on the Bay side, a large blue pennant flag was seen atop the old Ridgely House, one of several coastal militia reconnaissance lookouts. The signal was observed at Fort McHenry, more than 10 miles distant, which, in turn, fired three cannon to signal the city of the enemy’s approach. The London-cast belfry bells in Christ Church joined in sounding the alarm. The battle for Baltimore had begun.

At 3:00 p.m., Brigadier General John Stricker’s Baltimore Third Brigade of 3,185 militia marched six miles from Baltimore, encamping at the Trappe-North Point Road near a red-framed Methodist Meeting House nestled against a woodland known as “Godly Woods.” Before them stood a large, level, partially cleared field across which the British would have to pass. That evening, Stricker advanced a reconnaissance force of the 1st Rifle Battalion two miles ahead, accompanied by Lieutenant Colonel James Biays’ 5th Maryland Cavalry, who were deployed near the unfinished earthworks at Humphrey’s Creek. Stricker’s strategy was to carry on a succession of delaying skirmishes, rather than a pitched battle. As such, he left behind some 30 pieces of artillery, taking only Captain John Montgomery’s Baltimore Union Artillery militia unit’s four six-pounder field guns.

The popular name for the engagement that took place the next morning — the Battle of North Point — does not reflect the geography of where fighting occurred. North Point lies at the southern tip of the Patapsco Neck on the Bay shore, some five miles south of the battlefield. Those who fought there would have known the clash as the Battle of Patapsco Neck, the Battle of Long Log Lane or the Battle of Godly Wood.

The “Shot Heard ’Round the Chesapeake”

With only a blanket, a canteen and three days’ rations apiece, the British columns moved up the North Point Road. In the forefront were Ross and Cockburn; the infantry’s second in command, Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Brooke, would follow after supervising the landing parties at North Point. The British continued through a line of unfinished American breastworks (the site originally intended for the engagement), overcoming civilian workers and taking prisoner three American cavalry. Disdaining reports of the strong militia ahead, Ross allegedly boasted, “I don’t care if it rains militia, I shall sup in Baltimore tonight or in hell.”

At 1:00 p.m., Ross and Cockburn mounted their horses with an advance of 50 soldiers of the 85th King’s Light Infantry to reconnoiter a British picket who had made contact with the Americans ahead. Within moments, the British campaign was turned on its head: Without adequate protection, Ross — “gaily dressed, and glittering in all the bravery of scarlet and gold” of a major general — rode forward and was mortally wounded by sharpshooters in the woods. The victor at Bladensburg and Washington expired as he was carried back to the fleet. Brooke assumed command and pressed the “forlorn hope” back to Stricker’s main defense lines.

Brigadier General John Stricker’s brigade, with its effective force of 3,185 men, had quickly formed into three defense lines that morning when word was received of the British landing. The first, best-disciplined line would receive the initial attack, then fall back 300 yards to the second line. The 6th Maryland regiment was held a mile to the rear in reserve. Meanwhile, two miles south of these lines, at the mouth of Bear Creek, Major Beall Randall’s Rifle Battalion — sent by Stricker the day before to reconnoiter the water approaches to the battlefield — came under barrage by British artillery and Congreve rockets and, fearful of envelopment, returned to Hampstead Hill, protecting the right flank near the shoreline as it withdrew.

Captain John Montgomery’s militia Baltimore Union Artillery commenced the battle, followed by mass musket volleys of the flanking 5th and 27th Maryland Regiments. The British enjoined and began a flanking movement to turn the American left, which began to waver. Two of the Union Artillery six-pounders were moved from the center to bolster the left, along with the 51st and 39th Maryland, which were brought up to support the 27th, as it reeled from the onslaught.

At this critical juncture, the 51st was panic struck, carrying with it the 39th Maryland and reducing the American lines to just 1,000 men. After two hours of unrelenting volleys and unable to secure his failing flank and center, Stricker ordered a steady withdrawal from the field. Both lines moved to the rear, where the 6th Maryland was arrayed on a small rise on the north side of Bread and Cheese Creek. The combined American regiments stopped further British advance by late afternoon and removed steadily to the high promontory defenses of Hampstead Hill (today Patterson Park). From here, reinforced with the Naval Regiment under Commodore John Rodgers and 15,000 militia with 42 pieces of artillery, the Americans commanded the landscape. To prevent any British structural cover in front of the lines, a 1,000-foot-long wooden ropewalk was set alight.

It rained that night and into the next morning, saturating the landscapes while soldiers on both sides huddled around campfires or in farm outbuildings in an attempt to keep dry. From the heights of Hampstead Hill, all eyes looked east and south along the North Point Road. Two miles below, arrayed around Fort McHenry, ships’ masts took shape out of the gloom, signaling preparations for bombardment. The British army formed up on the North Point Road and, by 7:00 a.m., had set off through the open fields of manor estates toward the “Gates of Baltimore,” five miles distant.

Related Battles

28

1