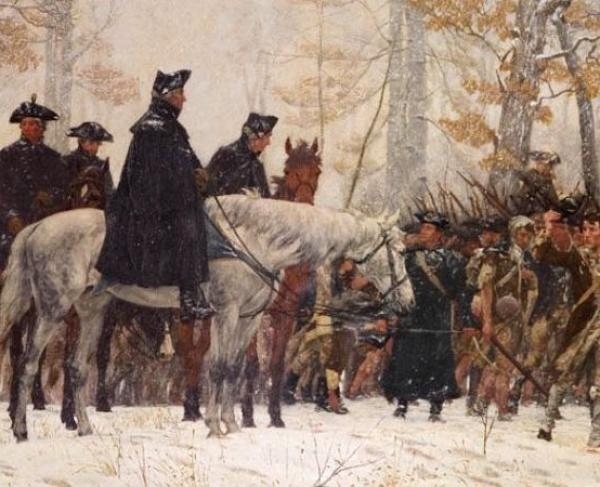

Two days before Christmas in 1777, George Washington, commanding officer of the Continental Army, then encamped at Valley Forge, sat down at his writing desk in the Isaac Potts house to draft a letter. The recipient was Henry Laurens, president of the Continental Congress. The missive contained a shocking warning to Laurens:

“…I am now convinced beyond a doubt, that unless some great and capital change suddenly

takes place in that line this Army must inevitably be reduced to one or the other of these three things. Starve—dissolve—or disperse, in order to obtain subsistence in the best manner they can.”

To underscore the importance and to remove any doubt that he was exaggerating he ended his letter with the following,

“Sir, this is not an exaggerated picture, and that I have abundant reasons to support what I say.”

The Continental Congress jolted into action, vowing to rectify the situation as it was “a Matter of great Importance and immediate Necessity” and included the appointment of a quartermaster general which had been vacant since General Thomas Mifflin had resigned the post in November 1777. Unfortunately for the rank and file of the Continental Army, the decision on Mifflin’s replacement would stretch into early March.

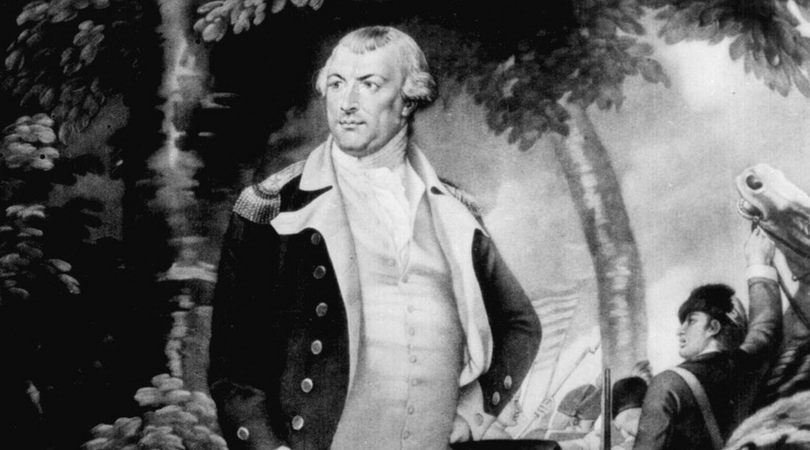

On March 2, 1778, Rhode Island native and major general in the Continental Army, Nathanael Greene ruminated over the task laid before him. His commanding officer, General George Washington, had notified him that he was tabbed to assume the role of quartermaster general. Although an integral position in any army at any juncture of history, Greene was loath to give up a combat command for one that was purely administrative. His own thoughts about the new position were best summed up when he put pen to paper and wrote, “No body ever heard of a quarter Master, in History.”

Washington stressed the importance of Greene accepting the role as quartermaster general, replacing Mifflin, and bringing permanency and stability to the department. The army was in dire straits in their winter encampment at Valley Forge, resorting to desperate measures to keep soul and body together. Greene relented, accepting the position on March 23 for the good of the cause of American independence, and the guarantee that his rank in line, his major generalship, would not be deprived of him. This allowed him the opportunity to return to a field assignment, which in 1780, landed him as the commander of Continental forces in the Southern Department.

After accepting the appointment, Greene quickly went to work. His first order of business entailed selecting two individuals that Greene trusted with staff positions to report directly to him. John Cox, an eminent Philadelphia merchant, assumed the responsibility of overseeing all purchases and examining the stores that were bought. Charles Petit received the task of keeping the books, recording the purchases, and overseeing the cash of the department. To Greene fell the military duties required from the quartermaster department, maintaining the order levels of supply warranted by the army and the issuance of said supplies to Washington’s force. As compensation, the Continental Congress decreed that the quartermaster department could keep 1% of the money spent divided as the three, Greene, Cox, and Petit, agreed upon. Each of the three received roughly one-third of one percent.

Nine days after assuming the role, Greene, harkening back to his pre-war days in Rhode Island in business as proprietor of his family’s foundry operation, started to make sense out of the chaos. He ordered a deputy quartermaster to record “every place where you find publick stores, what they are, and in whose hands” as “There has been great losses sustained for want of attention.” Clearer record-keeping was a necessity, especially after Greene realized his predecessor did not pay much attention to detail. In a letter to Laurens dated March 26, Greene highlighted the deplorable condition and lack of reporting his inherited department was in: “I have not received any Returns from General Mifflin, and therefore can only conjecture as to the full Extent of our Wants.”

An audit was conducted of Mifflin’s tenure as quartermaster general to root out corruption and irregularities of the system. Greene soon heard from disgruntled creditors about their lack of interest in working with the Continental government or army again, due to the lack of payment from prior business dealings when working with Mifflin. In further correspondence with Laurens, Greene counted on “a large and immediate supply of cash” to be authorized by the Continental Congress to entice merchants to do business with the army again. To initiate a new regime dedicated to doing business fairly with local merchants and suppliers, Greene took out advertisements in local pro-patriot newspapers. His message was twofold; acknowledge the poor business practices of his predecessor and promising to pay the going rate (and in some cases overpaying when necessity warranted) to gain the trust and confidence of suppliers, farmers, merchants, and other business owners that supplied the army.

Greene’s administration “of his Department [was] vigorous” as he sought to straighten out the intricate web of tangled lines that was Mifflin’s final legacy within the quartermaster department. He even paid a visit to the Pennsylvania legislature to propose amendments to the state’s wagon law. In reference to wagons, Greene even supplemented land with water carriage, utilizing the Schuylkill River until mid-May, when water levels dropped too low, to move cargo. Instead of moving all foodstuffs to camp, Greene approved an idea from the Commissary General of Cargo, Clement Biddle, for establishing a line of forage depots of various sizes to aid and sustain future movements of the Continental Army. This idea also won sanction with George Washington.

Biddle’s plan called for 200,000 bushels of grain, along with hay at the depots along the Schuylkill, Delaware River, and at Head of Elk in Maryland. Another 100,000 bushels along the stretch from the Susquehanna River to the Schuylkill and from the Hudson River in New York to the Delaware River. At Trenton, the scene of Washington’s signal victory in December 1776, another 40,000 bushels would be housed. Greene’s goal was to safely store over 800,000 bushels of grain in these supply depots situated approximately 15 miles apart from each other.

Hardly a week had elapsed in Greene’s new role when various supplies, random items that any army utilizes, including tent cloth, shovels, spades, and tomahawks began to arrive in Valley Forge. With the arrival of spring and eschewing the extra cost, Greene ensured emergency foodstuffs and clothing were delivered to the soldiery of Valley Forge. Rum and whiskey appeared, a welcome drink for all echelons of the army at any time, but especially after enduring the winter season.

By mid-April, reports out of Valley Forge showed how quickly Greene’s changes were starting to take effect, as the army became fairly well-supplied. Greene even strove to provide fodder for the horse population, the backbone of any 18th century army, yet he could not perform miracles or reverse the four months of inattention prior to the appointment. By June 1778, over 700 horses had perished due to lack of forage or disease.

Greene’s effectiveness in revamping the quartermaster department came at a cost. With the depreciation of the Continental dollar, prices continued to rise for the goods Greene was authorizing purchase for. Furthermore, his closest friendship and connection to Washington led him to be a target of the Board of War, a body organized by the Continental Congress to oversee military issues and included within its number a few Washington detractors. One of the board’s members was Thomas Mifflin, ironically. Greene argued his case and even threatened to resign over a spat about the use of purchasing agents. Congress prudently sided with Greene to avoid his resignation at that juncture.

Greene labored on as quartermaster general even after the time the army was in camp at Valley Forge. In May 1778, the Rhode Islander instructed his agents to procure even more horses and wagons in preparation for the spring campaign. The work of a quartermaster general never ended. Rising inflation, depreciation of the Continental dollar, and questioning by the Continental Congress continued to plague Greene throughout his tenure. He unburdened his angst to Washington, after meeting with Congress in April 1779, in a letter that read in part as follows,

“I am more and more convinced there is measures taken to render the business of the quarter

masters Department odious…and if I have not some satisfaction from the Committee of Congress respecting the matter, I shall beg leave to quit the Department. I think I shall leave it upon as good a footing as possible to put it under the present difficulties.”

However, Greene soldiered on and his administration of the quartermaster department lasted until he resigned in June 1780. The tone and rhetoric of his resignation letter initially placed him in the crosshairs of a few irate congressmen. Washington weighed in and Greene’s commission as a major general in the infantry was saved. A few short months later, using the skill set he learned as quartermaster coupled with his experience in line command, Greene went south, to reverse the fortunes of the southern department for the cause of American independence.