Photographer Timothy O’Sullivan's May 1864 photograph captures Union soldiers cooling off in Virginia’s North Anna River.

While the summer season has come to a close and we welcome in the cool breezes and warm colors of fall, we can easily recall the past season’s blistering heat and how we coped. Between time spent relaxing beachside, enjoying a cool beverage, embracing the wonders of climate control and wearing light and breathable attire, we in the present-day can find comfort on even the most excruciatingly hot days of summer. While faced with some of the same sweltering conditions we endure today, the average Civil War soldier didn't have many of these amenities, nor the medical advances to treat various heat-related illnesses like heatstroke.

Utilizing today’s technology and expanded access to primary source material, we can understand the drastic climate and weather conditions these soldiers fought in during the dead of summer, and what steps they took and solutions they sought to keep cool and carry on.

The Sweltering Reality of a Civil War Summer

Currently, an average summer day in the Mid-Atlantic U.S. can be hot, humid, slightly breezy and/or stormy; you would’ve seen much of the same during the time of the Civil War. Stories have long circulated detailing weather conditions amid summer battles, but there wasn’t solid data to prove or disprove them until recently.

Born out of a partnership between historian Jeff Harding and meteorologist Jon Nese, Ph.D., this revelation relied upon primary-source weather observation data recorded during the war — including measurements of atmospheric humidity; reconstructed weather maps from the period using a program developed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA); and modern data collected over a 30-year period to analyze weather and conditions at sites of conflict.

At Gettysburg, data taken from nearby Harrisburg showed boiling results: the heat index read — at 2 p.m. on July 3, 1863, only one hour before Pickett’s Charge — 98° F, with a dew point of 76° F. At the time of the charge, it is estimated that the heat index read as high as 105° F, after factoring in the blistering sunlight and saturating humidity.

In the wider Gettysburg Campaign, battles in Virginia also saw unbearably high temperatures. With atmospheric data taken from Washington, D.C., the findings saw an absolutely blistering 95 to 118° F on the heat index at Second Winchester and Aldie . At Cedar Mountain , soldiers felt a slightly less sizzling but equally unnerving 109° F on the heat index.

Soldiering Wear and Tear

While battling the weather conditions, the average Civil War soldier also battled their own uniform, equipment load and the excessive fatigue of marching. Soldiers on both sides wore year-round uniforms made of wool or a wool-cotton blend. While these heavy, natural-fibered uniforms seem a far cry from the comfort of today’s standard issue 50/50 nylon-cotton army combat uniform, wool was durable, protective and held moisture-wicking properties. While these characteristics were beneficial in the cold, they could be fatal to the summer soldier under the weight of their gear and fatigue.

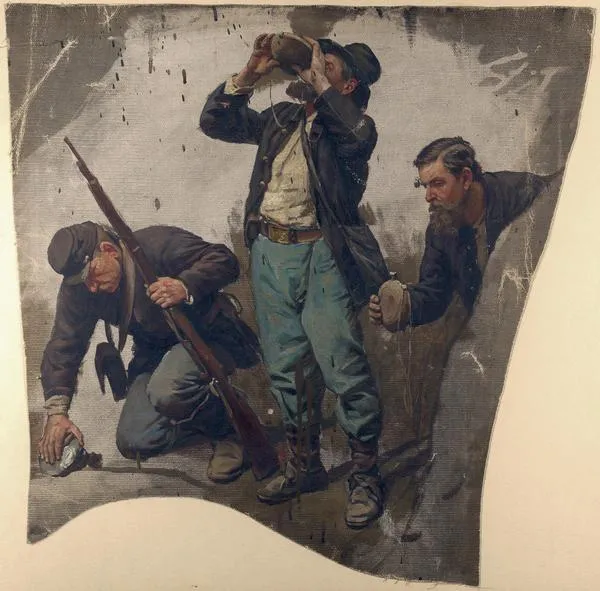

Soldiers carried a hefty load of essentials when marching , in camp and on the battlefield. In all, a soldier could carry upwards of 50 pounds of gear, consisting of their tent, blankets, personal items, clothes, food, canteen, musket cartridges, and other assorted items. Add in the fact that soldiers would typically march upwards of 15 to 30 miles a day, and you’ve got very fatigued soldiers that are not in top fighting condition.

One soldier of the 8th Virginia recalled , “Flesh and blood cannot sustain such heat and fatigue...I have seen men dropping, gasping, dying...weighs the heavy musket, muffling blanket, gripping waist band, and belt...chafing canteen straps-is it strange to see hundreds of men gasping for breath, and lolling out their tongues like madmen?”

Excessive sweating is the primary way the body cools itself. But the lack of evaporation from the weight of the gear and humidity caused many to develop skin irritations and severe dehydration.

A member of the 19th Massachusetts wrote in his diary , “the salty liquid got into the eyes, causing them to burn...and down the sides of the face which was soon covered with muddy streaks, the result of repeated wipings...”

Beating the Heat

Civil War soldiers exhausted efforts to cool themselves in the sweltering heat. The easiest method being taking a dip in a nearby creek or river while in camp. Another simple solution was to drink water to prevent severe dehydration brought on by excessive sweating. However, there were limited supplies of clean drinking water, as it was often contaminated by bacteria, sediment, or even some lively elements. One soldier of the 1st Tennessee recalled having tadpoles and other small fish frequently in his canteen.

For doctors treating severe heatstroke , practices changed over the course of the war. At the onset, many battlefield surgeons treated heatstroke by “simply pouring whiskey into his stomach,” as one surgeon did while stationed near Rappahannock Station in 1863. Older remedies proved common, but some American surgeons began adopting practices from British counterparts in India. These medical officers, who had worked in a year-round hot, humid climate, found that water was especially useful. By stripping a soldier down and pouring water on his head, over the throat, chest and along the spine, a soldier could quickly recover from heatstroke-related convulsions.

With such realizations, soldiers were keen on bringing a liberal amount of water in their kits, and medical officers recommended to commanders to provide “free supplies of water and rest to lessen the production of heat.”

Today, we have access and convenience that a Civil War soldier could never imagine. We can easily obtain lightweight clothing, and the modern military has even accounted for comfort in combat wear. We can walk to a sink to seek out tap water, or the refrigerator for a filtered variation. We have Gatorade and electrolyte-filled drinks on store shelves. And many across the U.S. know the cooling sensation provided by an air conditioning unit.

By more clearly understanding the weather conditions, thanks to advances in research and technology, we can better grasp a few more of the hardships that soldiers faced during this perilous time.