It's Raining Cats and Dogs

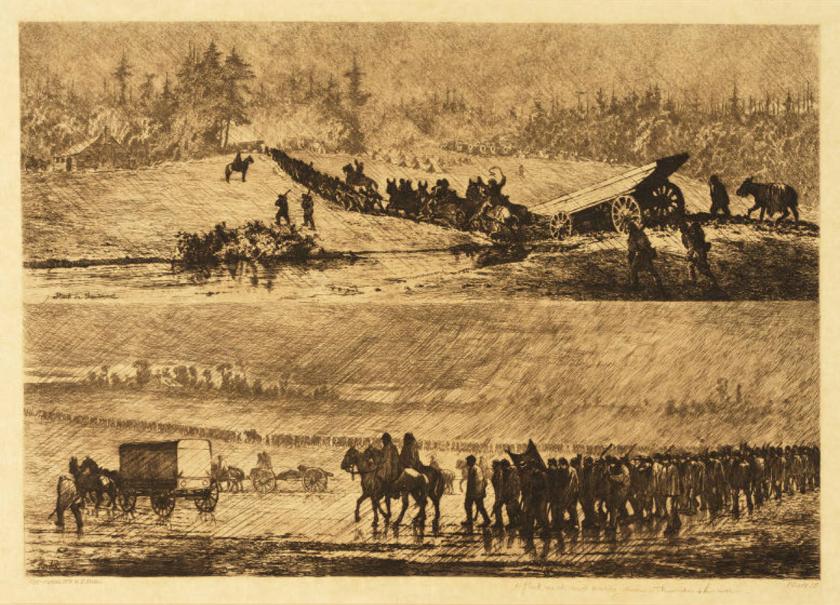

Alfred R. Waud's sketch of Union forces coping with the challenge of winter weather in 1863 as they advanced toward the Rappahannock River.

Weather and climate can carry heavy consequences for humanity... whether it comes in waves, eruptions, downpours, earthquakes, tornadoes, droughts or another of Mother Nature’s many obstacles. Sometimes, these environments can set already-strained situations ablaze — like a match to a pool of gasoline. Consider the fate of Napoleon’s army as it tried to invade Russia during the winter. Or how the monsoons of Southeast Asia have dictated or derailed campaigns across that region.

This correlation held just as true during the Civil War, when great droughts, unnaturally intense rains, and atmospheric phenomena played a significant role in every theater of the war.

Climate and Resilience in The East

In the Eastern Theater, there were plenty of times that weather helped or hindered the objectives of both Union and Confederate troops. Perhaps the most infamous were the precipitation irregularities that stymied the Union army following the Battle of Fredericksburg. Chiefly, a combination of unusually heavy winter rains and poor infrastructure further demoralized the Union forces under Ambrose Burnside.

Attempting to turn over a new leaf and leave behind the disaster that had unfolded at Fredericksburg, Burnside ordered the whole army to march downriver in January 1863 to cross under the cover of a cavalry feint upstream. But heavy rains exacerbated by massive deforestation — due to soldiers burning the surrounding woods for warmth — caused the already bad roads of Central Virginia to deteriorate further. In what is remembered as “The Mud March” and “The Union’s Valley Forge,” the Army of the Potomac became hopelessly mired in mud that was supposedly so deep and thick as to have swallowed entire gun carriages and limbers of artillery.

Brig. Gen. Daniel Woodbury summarized the new reality: “The rain has prevented surprise, and changed our condition entirely.” With Burnside’s grand vision drowned in the muck and mire, Richmond went unchallenged and the war stretched on for three more years.

Drought and Disaster in the West

But weather doesn’t play favorites or confine itself to geographic areas. Climatic events in the Western Theater also had tactical effects that influenced the trajectory of the entire war.

La Niña, a period of cyclical cooling over the Pacific Ocean, coincided with the critical 1862 Heartland Campaign in Kentucky and Tennessee. The cooler oceanic temperatures reduced precipitation in the western and midwestern United States, leading to months of severe drought throughout Confederate territory. In part, this lack of easily sourced drinking water motivated Braxton Bragg’s army to coalesce around Perryville where, it was thought, Doctor’s Creek could provide water for his men and horses before marching northward. Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell and his Union Army of the Ohio responded to the Confederate movement, despite intense dehydration and sickness stemming from the conditions, and positioned themselves for a clash.

In the ensuing battle, Bragg was dealt a strategic defeat which forced him and the remaining Confederate forces back into Tennessee, setting the stage for a more consistent Union effort in the west.

Furthermore, the drought of 1862 caused enormous crop failures all throughout the south. This, combined with Union blockades preventing imports, shifting population patterns as refugees fled to cities, inflation, and the need to funnel supplies to field armies, led to widespread bread riots across the South, especially Richmond, in the spring of 1863.

The effects of climate, an actor with neither good nor ill will towards our country’s discord, played a huge role in the ending of the conflict. Though better prepared for disaster than the Union Army of 1863, we still face issues of lackluster infrastructure in the face of severe weather events, impacting both civil and military matters around the globe. It is incumbent that we remember how the Earth retains an active and unpredictable hand in the matters of war and peace.