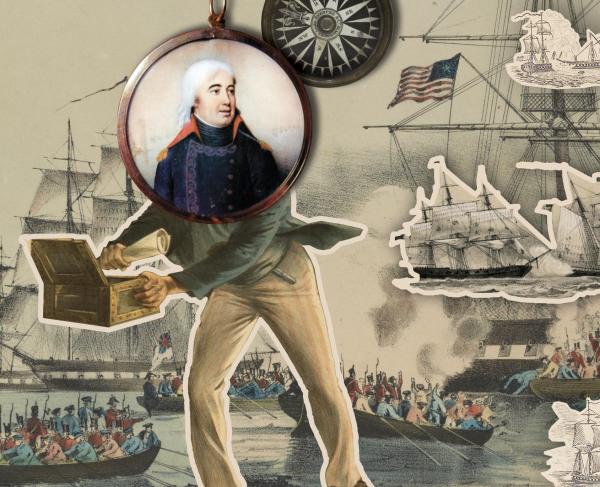

The USS Constitution engages the HMS Guerriere

Naval combat in the Age of Sail, which lasted from the 16th to mid-19th century, may seem strange to the modern eye. Sailing ships were virtually floating villages, with the largest ships of the line armed with more artillery than some armies. Because of a ship’s dependence on the wind for propulsion, combat often resembled a deadly dance between combatants, which could disintegrate into a bloody close-range brawl.

It is important to understand the different types of warship that plied the waves during this period, which applies to both the American Revolution and War of 1812. The largest naval vessels were the ships of the line and often classified by the British rating system: first-rate, second-rate, and third-rate. These slow and heavily armed ships would form the core of a battle line and exchange fire with their similarly sized adversaries.

The third-rate formed the backbone of many navies, especially the British, and usually mounted seventy-four guns on three decks, with a crew of up to 700 men. The largest, first-rates, were massive in terms of size and firepower. The most famous example, HMS Victory, Admiral Nelson’s flagship at Trafalgar, mounted 104 cannon, firing a broadside weight of 1,148 pounds, and needed a crew of 800 to fight and sail.

During the American Revolution and War of 1812, the large fleet battles of Europe were rare, with combats between smaller Frigates, Sloops, and Brigs far more common. These ships were not designed to fight on the line, but were used as “cruisers” because of their speed, maneuverability, and range. They were often allowed to cruise independently, searching for enemy targets of opportunity, or attached to large fleets as scouts, pickets, and couriers. Many of the most famous actions of both wars were duels between these smaller, yet deadly, ships.

USS Constitution vs. HMS Guerriere, August 19, 1812, 400 miles SE of Halifax, Nova Scotia.

USS Constitution was one of the “original six” frigates ordered in 1794. Knowing that the fledgling US Navy could not match the European powers on the water, these ships were designed to be faster, hardier, and fire a heavier broadside than their European counterparts; enabling them to overpower similarly sized ships and evade the larger ships of the line. Constitution, considered a heavy frigate, mounted forty-four guns with a crew of 450. HMS Guerriere, captured from the French in 1806, was a British fifth-rate frigate, with thirty-eight guns and a crew of 272.

On August 19, 1812 at two PM, early in the War of 1812, Constitution, with Captain Isaac Hull in command, sighted an unknown ship on the horizon and decided to investigate. Previously, the Constitution had tangled with the large British fleet, including Guerriere and her Captain James Richard Dacres, but managed to escape. Both ships recognized each other at the same moment, and cleared their decks for combat.

Initially, Guerriere fired a broadside that fell short, turned into the wind and ran, occasionally yawing to fire a broadside at the pursuing Constitution. During this forty-five minute chase, a cannonball bounced harmlessly off the Constitution, earning her the enduring nickname “Old Ironsides.” When Constitution closed the gap to a few hundred yards, Captain Hull ordered extra sail to quickly cover the final distance. Guerriere did not mirror this maneuver, and both ships closed to “half pistol-shot,” point-blank range, and began exchanging broadsides.

For fifteen minutes, both ships hammered each other, but the heavier guns and stronger hull of Constitution proved highly effective. Guerriere lost her mizzenmast, which fell overboard and acted like a large rudder, pulling the ship around. Taking advantage of Guerriere’s immobility, Constitution crossed to the vulnerable front of the enemy ship, and delivered a punishing broadside, raking Guerriere from stem to stern, causing the Guerriere’s mainmast to also fall. The Constitution came about and raked her foe again, but during this maneuver, both ships became entangled. Boarding parties were formed on both ships, but were unable to cross the tangled rigging and bowsprit in the heavy seas.

The ships remained tangled, exchanging cannon and musket fire, until they rotated and broke free. Guerriere attempted to set sail and flee, but her masts and rigging were so heavily damaged this proved impossible. Constitution managed to disengage briefly and make repairs to her rigging, before moving to bear down on Guerriere once again. Sensing that his ship would not survive another assault, Captain Dacres, who was wounded by a musket ball, signaled his surrender by ordering a cannon fired in the opposite direction of Constitution. Hull ordered a Lieutenant rowed to the enemy ship to investigate, who asked if Guerriere was surrendering, to which Dacres responded, “Well, Sir, I don’t know. Our mizzen mast is gone, our fore and main masts are gone – I think on the whole you might say we have struck our flag.”

On the American side, casualties and damage was light, with seven killed and seven wounded. The British, however, suffered dramatically, with fifteen killed, seventy-eight wounded, and the remaining 257 captured. Captain Hull refused to accept Dacres sword of surrender, honoring his gallantry and a battle well fought.

Hull attempted to salvage Guerriere and tow her to port, but, despite working all night to save the ship, the damage was too extensive and he instead ordered the sinking ship burned. Wanting to provide the Americans with a morale boost, Hull sailed to Boston to deliver the news, which was received with great enthusiasm.

USS United States vs. HMS Macedonian, October 25, 1812, near Madeira.

USS United States was the first of the “original six” commissioned under the Naval Act of 1794. She was a heavy frigate, mounting forty-four guns with a crew of 450. HMS Macedonian was a new addition to the Royal Navy, commissioned in 1810. She was a thirty-eight gun fifth rate frigate, and had a complement of 306.

United States, under the command of Captain Stephen Decatur, sailed from Boston in early October on a long Atlantic cruise searching for British merchant shipping and warships. At dawn on October 25, near the island of Madeira off the North African coast, the United States spotted a ship and identified it as Macedonian, with Captain John Surman Carden in command, en route to its West Indies station. Both ships cleared for action and closed the distance. Decatur wanted to keep the British warship at range, using his heavier twenty-four pounders to disable the ship before closing to finish the job.

Around 9 AM after exchanging initial broadsides, the United States’ second volley destroyed Macedonian’s mizzen topmast and gave the maneuver advantage to the American frigate. United States took up position on Macedonian’s rear quarter, a highly vulnerable area for the British ship, and proceeded to hammer the hapless vessel. By noon, the United States had reduced Macedonian to a dismasted, floating hulk. When Decatur closed for another broadside, Carden struck his colors and surrendered.

The aftermath revealed a one-sided battle, with the heavier guns and longer range of the American frigate proving devastating. Macedonian had over 100 round shot lodged in her hull alone, and suffered forty-three killed and seventy-one wounded: thirty percent casualties. The United States had seven killed and five wounded. United States delivered seventy broadsides, while Macedonian replied with only thirty.

The two former combatants lay alongside each other for two weeks so that Macedonia could be repaired to a sailing state. Decatur sailed back to the United States with his prize, arriving in Newport, Rhode Island, on December 4. HMS Macedonian was then bought and commissioned into the United States Navy, serving as USS Macedonian. Decatur and his crew were lauded for their spectacular victory, and praised by the public, congress, and President Madison.

USS Chesapeake vs. HMS Shannon, June 1, 1813, Boston Harbor.

With the War of 1812 progressing into its second year, the United States had acquired a string of naval victories, seriously damaging British morale and perceived naval superiority. With this in mind, Captain James Lawrence had finished refitting USS Chesapeake in Boston Harbor, and was eager to sail out and engaged the British. Chesapeake was smaller than her sisters Constitution and United States, rated as a thirty-eight gun frigate, with a crew of 379. Shannon, commanded by Captain Phillip Broke, was of the same size and armament, but had her crew reduced to 330 after capturing a number of merchantmen.

The Royal Navy’s crew’s had suffered during the Napoleonic Wars, and were not of the same quality that they used to be, with this in mind Lawrence expected to overpower Shannon despite their equal size and armament. The Shannon’s crew and Captain, however, were not average British sailors. Broke was a superlative officer, and a master of naval gunnery, who drilled his crew into an excellent force. Lawrence, on the other hand, had some experienced crewmen, but many had not fought together or onboard Chesapeake before.

Chesapeake sailed out to meet Shannon on June 1, 1813, and sighted her adversary around five PM. With the Chesapeake bearing down on them, Broke offered his simple gunnery philosophy to his crew, “Throw no shot away. Aim every one. Keep cool. Work steadily. . . . Don’t try to dismast her. Kill the men and the ship is yours.” After months at sea, Shannon was shabby compared to the newly refitted Chesapeake, which gave Lawrence even more confidence in his attack.

The two Captains opted to hold their fire until they could exchange broadsides, making the engagement as much a duel between gentlemen as a duel between warships. At six PM, at a range of thirty-five meters, both sides opened fire. Immediately the methodical, accurate, fire of the British crew took its toll on the American ship, with her forward gun crews suffering badly. The Americans, however, steadily returned fire and inflicted some damage.

Realizing that his ship was moving too quickly and would overtake Shannon, Lawrence ordered a reduction in speed. During this maneuver, the accurate British fire swept the Chesapeake’s quarterdeck, killing the helmsmen and disabling the wheel. The Chesapeake was able to land addition hits on the Shannon and swept her forecastle with carronade fire. Finally, a shot carried away Chesapeake’s topsail halyard, causing her to lose all forward momentum and leaving her dead in the water.

The Chesapeake’s rear left quarter was caught by the Shannon’s anchor, and the British lashed their ship to their adversary and prepared to board. Caught at an angle where her guns could not fire on the British ship, and where the Shannon could fire into her vulnerable stern and rake the ship, the Chesapeake was in grave danger. Sensing his opponent’s weakness, Broke ordered his men to board. At the same time, Lawrence also decided to board his opponent, but his order was lost in the maelstrom and only a few Americans followed their captain.

Before Lawrence could lead his men into the enemy ship, he was stuck by a musket ball and mortally wounded. As he was being carried below he called out the now famous, “Tell the men to fire faster! Don’t give up the ship!” With all but one American officer wounded the British faced little organized resistance when Brock led his highly organized crew aboard. While the Americans resisted, and even managed to push the British back at one point, there was little hope. Even though Brock himself was badly wounded by a cutlass to the head, and the British boarding party was stranded when the two ships separated, American resistance had effectively ceased. The close-range and brutal engagement had lasted a mere fifteen minutes.

Both sides suffered heavily, Chesapeake lost forty-eight killed, ninety-nine wounded with the rest captured, Shannon twenty-three men killed, and fifty-six wounded. In terms of gunnery, the Chesapeake had been soundly beaten. The British sailed their first major prize of the war to Halifax and were greeted jubilantly. USS Chesapeake was recommissioned HMS Chesapeake. Captain Lawrence was buried with full military honors, with six Royal Navy officers acting as pallbearers. Brock, though initially not expected to survive his wound, returned to Britain a hero, given a Baronet, and knighted. Though disabled, he continued his career as a gunnery instructor.

In terms of casualties compared to number of men engaged, the engagement between Chesapeake and Shannon had not only been the bloodiest in the War of 1812, but one of the bloodiest in the entire Age of Sail. For comparison purposes, Chesapeake and Shannon suffered more casualties in fifteen minutes than HMS Victory suffered during the entire Battle of Trafalgar.

Capture of USS President, January 15, 1815, New York Harbor

As the War of 1812 progressed, and the British realized the danger of the American heavy frigates, they dedicated more and more naval assets to blockading the American coast. In addition, the British strictly prohibited their ships from challenging the American frigates one-on-one. After numerous attempts to run the British blockade, Commodore Stephen Decatur transferred his command to President, one of the forty-four gun heavy frigates, which was trapped in New York by a British squadron of four ships commanded by Commodore John Hayes.

On January 13, with a blizzard raging that blew the British ships off their station, Decatur decided to break out of New York Harbor. Unfortunately, the harbor channel had not been well marked, and President grounded on the bar. For two hours, with high winds and heavy seas, President struggled on the bar, suffering heavy damage to her hull and rigging. The winds prevented Decatur from returning to port forcing the damaged President to sea.

After the storm cleared the British, realizing that the Americans may have attempted a breakout, took up positions to intercept any American ships. At dawn on January 14, British ships spotted President and immediately moved to engage. Decatur turned his ship downwind in an attempt to escape, even lightening President by throwing unnecessary items overboard, but the damage sustained in the harbor proved disastrous.

With the British frigates Majestic, Endymion, Tenedos, and Pomone all giving chase, a running battle ensued, with both sides trading fire and the British steadily closing. By nightfall Endymion was able to close the gap, and poured devastating fire into President’s vulnerable rear quarter. A quick maneuver by Decatur laid both ships alongside one another, trading broadsides. The Americans targeted the British rigging to hasten their escape from the remaining British vessels, while the British gunners pounded the President’s hull.

At 8 PM, Decatur struck his colors and Endymion stopped to make hasty repairs to her rigging. Seeing the British stopped but not launching any boats, none were seaworthy, Decatur hoisted his sails and attempted to escape at 8:30. Endymion was under sail by 9, and Pomone and Tenedos had caught up. Two rapid broadsides from Pomone finally decided the issue, and Decatur again struck his colors.

In the engagement President lost twenty-four men killed, fifty-five wounded and the rest of her crew of 447 captured, while the Endymion, the only British vessel to suffer casualties, lost eleven killed and fourteen wounded. Soon after the engagement the War of 1812 ended, thus ending the frigate duels of the Atlantic.