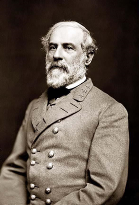

In the spring of 1864, the Union's new commander-in-chief, Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, launched a coordinated nationwide offensive to defeat the major Confederate armies and bring the rebellion to a close. In the war's western theater, Grant's trusted subordinate Major General William T. Sherman was to direct the drive against General Joseph E. Johnston's Confederate army barring the way to Atlanta. In the east, Grant undertook to supervise a three-pronged attacked against the rebellion's premier fighting force, General Robert E. Lee's storied Army of Northern Virginia. The Federal Army of the Potomac—commanded by Major General George G. Meade and accompanied by Grant—was to initiate the main attack against Lee, supported by Major General Franz Sigel's incursion through the Shenandoah Valley and Major General Benjamin F. Butler's foray against the Confederate capital, Richmond, Va. Battered by Meade's massive Potomac army, denied supplies by Sigel's Valley incursion, and harassed in the rear by Butler, Lee would be cornered and brought to bay. Grant's plan was a thoughtful exercise carefully drawn to bring the war in the east to a swift conclusion.

The campaign, however, got off to a rocky start. Crossing the Rapidan River downriver from Lee on May 4, 1864, the Army of the Potomac became ensnared in a grueling, two-day battle in the inhospitable Wilderness of Spotsylvania. Fought to impasse, Grant directed Meade to withdraw and sidle ten miles south to the cross-roads hamlet of Spotsylvania Court House, expecting that Lee would follow and give battle on terrain more favorable to the Union host. Lee, however, won the race to Spotsylvania Court House and barred Grant's progress with an imposing line of earthworks. During the ten bloody days spanning May 8 through May 18, the Army of the Potomac unleashed a welter of assaults, but Lee's Spotsylvania line could not be broken. Disheartening news also reached Grant from his supporting armies; Confederate forces had defeated Sigel at New Market and Butler at Drewry's Bluff. The campaign that had started two weeks before with so much promise seemed about to unravel.

Grant’s and Meade’s relationship was also fast becoming a victim of the campaign. Concerned over Meade’s inability to defeat Lee, Grant increasingly kept major battlefield decisions for himself, relegating to Meade matters ordinarily handled by staff officers. The crusty Pennsylvanian’s letters home bristled with hurt. “If there was any honorable way of retiring from my present false position, I should undoubtedly adopt it,” Meade wrote his wife, “but there is none and all I can do is patiently submit and bear with resignation the humiliation.” Meade’s aides were especially venomous and derided Grant as a “rough, unpolished man” of only “average ability, whom fortune has favored.” Grant’s staffers in turn complained that Meade was uncommitted to the spirit of their boss’s hard-hitting offensives. “By tending to the details he relieves me of much unnecessary work, and gives me more time to think and mature my general plans,” was Grant’s excuse for keeping the Pennsylvanian on.

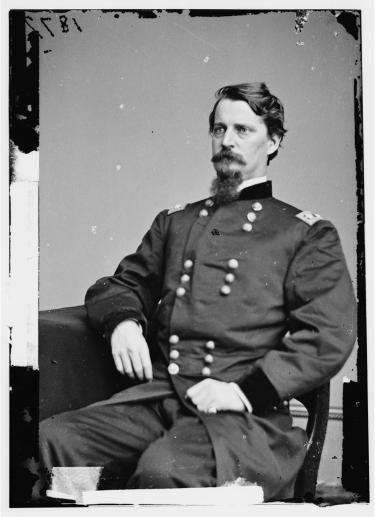

Undaunted by setbacks on the battlefield and discord among his generals, Grant devised a new plan to entice Lee from his Spotsylvania defenses. Hoping to lure Lee into the open, he directed Major General Winfield S. Hancock to take the Union army’s Second Corps on a twenty-mile march southeastward through the town of Bowling Green and on to the hamlet of Milford Station. If Lee left his entrenchments to attack Hancock as Grant expected, the remainder of Meade’s army was to pounce on the Rebels and crush them. In short, Hancock would serve first as bait to draw Lee from his fortifications, and then become the anvil against which Grant would hammer his opponent. In the event that Lee ignored the bait, Hancock would simply continue on to the North Anna River, the next major river line toward Richmond, clearing the way for the rest of the Union army to follow.

Grant's analysis took into account the terrain that Meade's soldiers would have to traverse. Telegraph Road offered the Federal army the most direct path south but required it to cross the Ni, Po, and Matta rivers, risking opposition at each stream; a few carefully positioned Confederates could delay Grant's progress while Lee's main body pursued parallel roads and beat him to the North Anna River. A few miles east of Telegraph Road, however, the Ni, Po, and Matta merged to form the Mattaponi, which flowed due south. By swinging east from Spotsylvania Court House, Grant saw that he could circumvent the bothersome streams and descend along the Mattoponi's far side, using the river system to shield his forces from attack. In the inevitable race south, Lee, not Grant, would have to cross the irksome tributaries.

During the night of May 20-21, Hancock began his diversionary march. When Lee learned of the Union movement, he concluded that Hancock was spearheading an advance to Richmond and threw a part of the Confederate army across Telegraph Road, closing the main highway south to the Federals and severing Hancock from the rest of the Federal force. Growing increasingly concerned over Hancock's safety, Grant directed Meade to evacuate his entrenchments at Spotsylvania Court House and rush to Hancock's assistance. Once again, an operation that Grant had begun as an offensive thrust was assuming a decidedly defensive tone.

Nightfall saw the Army of the Potomac in disarray. Hancock, separated from the rest of the Union force, sparred with Confederates sent from Richmond to reinforce Lee. Meade meanwhile attempted to batter his way down Telegraph Road but was brought up short by Lee's new defensive line. Backtracking, the entire Federal army set off to circumvent Lee by following the looping route that Hancock had taken the previous day. That night, Lee's troops completed their withdrawal from Spotsylvania Court House and tramped south toward the North Anna River; in places passing Meade's sleeping outposts by less than a mile. Union cavalry was absent on a raid, leaving Grant without intelligence of Lee's proximity, and the Federal commander's opening to catch Lee's army outside of its entrenchments went unexploited. "Never was the want of cavalry more painfully felt," a Northern officer fumed when he learned of the missed opportunity.

After a grueling night march, the Army of Northern Virginia's fagged-out troops crossed the North Anna on May 22 and went into camp a few miles south of the river at Hanover Junction, where the Virginia Central Railroad from the Shenandoah Valley crossed the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad. Anxious to protect this critical rail link a scant twenty-five miles north of Richmond, Lee chose Hanover Junction as the next place to make a stand.

Grant pushed south in Lee's wake on May 22, fanning the Army of the Potomac across a wide swath of countryside. Uncertain whether Grant meant to continue across the North Anna or swing farther to the east, Lee waited for signs of his adversary's intentions. The answer came the next day as the Union army's scattered elements converged at Mount Carmel Church, a handful of miles above the North Anna. From the church, Hancock marched toward the main river crossing at Chesterfield Bridge while Major General Gouverneur K. Warren took his Fifth Corps west along a side road, intending to cross a few miles upstream at Jericho Mill. Major General Horatio Wright's Sixth Corps followed behind Warren, and Major General Ambrose E. Burnside's Ninth Corps took another side road to Ox Ford, midway between Warren and Hancock. By day's end, the Army of the Potomac was slated to come together in a line along the river, with some or all of its troops across.

Nearing the North Anna, Hancock’s troops came under fire from Colonel John Henagan’s South Carolina brigade ensconced in a three-sided redoubt next to Chesterfield Bridge. Charging the isolated outpost, Hancock's men overwhelmed the defenders, capturing many of them and driving the rest back across the river. In short order, Henagan's redoubt and Chesterfield Bridge were in Union hands.

Five miles upstream, Warren scattered a handful of mounted Rebels at Jericho Mill. Union Engineers constructed a pontoon bridge, and by 5 p.m., the Federal Fifth Corps was tramping across the river and deploying in neighboring fields. Confederate scouts discovered the interlopers but underestimated their numbers, reporting to Lieutenant General Ambrose P. Hill, commanding Lee's Third Corps that only two Union brigades had crossed. Misled about the size of the Federal force, Hill sent a single division to repel the invaders. Warren easily resisted the attack but elected not to press his advantage as he was uncertain how many Confederates he faced.

With a formidable portion of Grant's army now ensconced on his side of the river, Lee recognized that he was in serious trouble. That evening, the Confederate general and his advisors met under a broad oak tree and concocted an ingenious scheme. The Army of Northern Virginia was to spread out into a wedge-shaped formation, its apex touching the North Anna River at Ox Ford and each leg reaching back and anchoring on strong natural positions. The tip of the wedge, perched on precipitous bluffs, was unassailable; and with the Virginia Central Railroad connecting the wedge's two feet, Lee could shift troops from one side to the other as needed. When Grant advanced, the wedge would split the Union army in half, enabling Lee to hold one leg with a small force while concentrating his army against the Federals facing the other leg. By cleverly adapting the military maxim favoring interior lines to the North Anna's topography, Lee had given his smaller army an advantage over his opponent.

All night, Lee's troops threw up earthworks. Hill's Third Corps deployed along the wedge's western leg while Lieutenant General Richard H. Anderson's First Corps formed the wedge's eastern leg. Lieutenant General Richard S. Ewell's Second Corps tacked onto the end of Anderson's line and comprised a reserve along with Major General John C. Breckinridge's troops, fresh from their victory over Sigel in the Valley.

The next morning—May 24—Lee fell seriously ill with dysentery and became "cross as an old bear," according to a witness. "General Hill, why did you let those people cross here," Lee snapped in questioning his Third Corps commander about his faltering performance at Jericho Mill the previous evening. "Why didn't you throw your whole force on them and drive them back as [Thomas J. "Stonewall"] Jackson would have done?" Lee's reproach must have cut deeply, but Hill held his tongue.

At daylight the entire Union army—the left under Hancock at Chesterfield Bridge, the center under Burnside at Ox Ford, and the right under Warren and Wright at Jericho Mill—made ready to push south. "The enemy have fallen back from North Anna," Grant wrote Washington in jubilation, unaware that he was marching into Lee's trap.

While the Union commanders celebrated an apparent victory, their subordinates encountered unexpected resistance. Assured by his superiors that Lee had retired, Hancock started his Second Corps across Chesterfield Bridge. Confederate artillery contested the advance, forcing Hancock to stop a short distance south of the river and wait for the rest of the army to move up next to him. More deadly was the fate of one of Burnside's brigades under Brigadier General James H. Ledlie, which crossed the North Anna near Ox Ford with orders to dislodge the Rebels holding the bluffs. To Ledlie's surprise, the heights were topped by earthworks still occupied by a veteran Rebel division under Brigadier General William Mahone. His judgment clouded by alcohol, Ledlie rode toward the heights accompanied by an aide twirling a hat on the point of his sword. "Come on, Yank," Rebels lining the works shouted, amazed that anyone would consider charging their stronghold. As a warning, a Rebel sharpshooter put a bullet through the aide's hat.

Ledlie rode on, his men following in orderly lines. Musketry exploded from the Confederate earthworks, and Ledlie's formation dissolved into a blue-clad mob. Artillery raked the field, thunder roared, rain fell in sheets, and Ledlie abandoned all pretense of command, abandoning his soldiers to their fates. "Nothing whatever was accomplished, except a needless slaughter," a Union officer observed, "the humiliation of the defeat of the men, and the complete loss of all confidence in the brigade commander who was wholly responsible." Astoundingly, Ledlie escaped censure and a few weeks later received command of a division, where he would cause even greater mischief.

While Ledlie pursued his ill-advised offensive, Hancock tried once again to probe south but was stopped by Anderson's strongly entrenched position on the wedge's eastern leg. Other of Hancock's troops followed the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railway south but were stymied by Ewell's Confederates. Ever optimistic, Hancock informed headquarters that his skirmishers were "pretty hotly engaged" but held onto the fiction that Lee's main body of soldiers had retreated. Assuming that he faced nothing more than a delaying force in rifle pits, he promised to continue to try and break through.

Lee's moment had come. His plan to split the Union army had worked, isolating Hancock east of the Confederate position, Burnside north of the river at Ox Ford, and Warren and Wright several miles to the west, near Jericho Mill. Hill, holding the Confederate formation's western leg, could fend off Warren and Wright while Anderson and Ewell, on the eastern leg, attacked Hancock with superior numbers. "[Lee] now had one of those opportunities that occur but rarely in war," a Union aide later conceded, "but which, in the grasp of a master, make or mar the fortunes of armies and decide the result of campaigns."

Lee, however, had become too ill to take exploit his opportunity. Wracked by dysentery, he lay confined to his tent. "We must strike them a blow," a staffer heard the general exclaim. "We must never let them pass us again. We must strike them a blow."

But the Army of Northern Virginia could not strike a blow. Lee was too sick to direct the complex operation, and his top echelon had been decimated. Anderson was new to his post, Ewell had proven unreliable, and Hill had exercised poor judgment at Jericho Mill. Physically unable to command and lacking a capable subordinate to direct the army in his place, Lee saw no choice but to forfeit his hard-won opportunity.

While Lee lay on his cot prostrated by sickness, Hancock made a final lunge. Pressing across the farm of the Doswell family, he came under even stiffer fire than before and bivouacked on the rain-soaked battlefield. Warren's and Wright's soldiers, massed between Jericho Mill and the Virginia Central Railroad, also advanced but ran against Hill's entrenchments and began constructing their own earthworks across from the Rebels. "To raise a head above the works involved a great personal risk," a Union soldier remembered, "and as nothing was to be gained by exposure, most of the men wisely took advantage of their cover." Nowhere did the Federals seriously threaten the Confederate line.

Near nightfall, Grant and Meade rode to the Fontaine house, south of the river. "The situation of the enemy," Grant conceded, was "different from what I expected." Rather than continuing to attempt an advance, he decided instead to feel out the contours of the Confederate position.

The next morning, May 25, Union infantry probes confirmed that the Rebel line commanded killing fields ever bit as imposing as those at Spotsylvania Court House. "The conclusion that the enemy had abandoned the region between the North and South Anna, though shared yesterday by every prominent officer here, proves to have been a mistake," a highly placed Federal noted. "The situation," one of Meade's aides observed, was a "deadlock," with the two armies pressed closely together like "two schoolboys trying to stare each other out of countenance."

A Union newspaperman reported that the "game of war seldom presents a more effectual checkmate than was here given by Lee." But the Confederate commander was also stymied. With the Union army pressed tightly against his lines, the only direction he could turn was south, toward Richmond. Having no other choice, Lee forfeited the initiative to Grant and awaited his enemy's next move.

That evening, Grant and Meade met with their generals to find ways to break the impasse. Some argued that a maneuver west of Lee would catch the Rebels off guard. Grant, however, vetoed that move. He needed to stay east of Lee, he insisted, to safeguard his supply routes back to the Chesapeake Bay.

Virginia's geography also recommended an eastern shift. Below the North Anna, the Union army would face three formidable steams—Little River, New Found River, and the South Anna River—each running west to east and only a few miles apart. High-banked and swollen from recent rains, the rivers would afford the retreating Confederates ideal defensive positions. A few miles southeast of Lee's position, however, the rivers merged to form the Pamunkey. By moving east of Lee and sidling downstream along the Pamunkey, Grant would put the pesky waterways behind him at one stroke. And White House, the highest navigable point on the Pamunkey, was ideally situated as Grant's next supply depot. In addition, as the Federals followed the Pamunkey's southeastward course, they would slant progressively nearer to Richmond. Grant's most likely crossings—the fords near Hanovertown, thirty miles southeast of Ox Ford—were only eighteen miles from Richmond; once the Army of the Potomac was over the Pamunkey, only the Chickahominy River would stand between them and the Confederate capital.

Having decided on his next move—withdrawing to the northern bank of the North Anna, driving thirty miles downriver, and crossing the Pamunkey near Hanovertown—Grant penned an optimistic dispatch. The decisive battle of the war, he predicted, would be fought on the outskirts of Richmond, and he had no doubt about the outcome. "Lee's army is really whipped," he assured Washington. "The prisoners we now take show it, and the actions of his army show it unmistakably. A battle with them outside of entrenchments cannot be had. Our men feel that they have gained the morale over the enemy and attack with confidence. I may be mistaken, but I feel that our success over Lee's army is already insured."

The most hazardous phase of the operation would be disengaging from Lee. Not only were the armies pressed tightly together, but they were on the same side of the North Anna, with Grant backed against the stream. As soon as Lee discovered that the Federals were leaving, he was certain to attack, and the consequences could be catastrophic. Grant's solution was a ruse. He would send a division of cavalry west of the Confederates to create the impression that he was preparing for an army-wide advance in that direction. After dark, the rest of the Potomac army would steal from its entrenchments in a carefully orchestrated sequence, cross to the river's northern bank, and head east. If everything went according to plan, the main Federal body would be streaming across the Pamunkey well on its way toward Richmond before Lee discovered the deception.

May 26 saw more rain, forcing troops of both armies to hunker low behind earthworks slippery with mud and knee-deep in water. By noon, Brigadier General James H. Wilson's Union cavalry division was crossing at Jericho Mill and setting out on its diversion. Riding west of the Rebel army, Wilson's men put on a conspicuous show. "Fences, boards, and everything inflammable within our reach were set fire to give the appearance of a vast force, just building its bivouac fires," a Federal rider remembered.

A Union infantry division meanwhile re-crossed the North Anna and began a looping march toward the Pamunkey. All day, wagons carried the army's baggage over the river and returned for fresh loads. Sightings of the constant wagon traffic persuaded Lee that the Union commander was planning some sort of movement, and Wilson's cavalry activity suggested that a shift west was in the making. From "present indications," Lee wrote the Confederate War Secretary, Grant "seems to contemplate a movement on our left flank." Grant's ruse had worked to perfection.

Shortly after dark, Meade began evacuating his entrenchments in earnest, concealing his departure with clouds of pickets. "Such bands as there were had been vigorously playing patriotic music, always soliciting responses from the rebs with Dixie, My Maryland, or other favorites of theirs," a Union man noted. Soldiers marched along rain-soaked trails in the pitch black, slipping in mud "knee deep and sticky as shoemaker's wax on a hot day," a participant recalled. One hole sucked troops in to their waists, and a few unfortunates reputedly disappeared over their heads in viscous ooze and suffocated. Miraculously, the last of the Federals were across the river by daylight. Engineers pulled up the pontoon bridges and a Union rearguard set fire to Chesterfield Bridge to delay pursuit.

By sunup, Lee understood that the Federals had gotten away and were marching east. Uncertain of Grant's precise route, he decided to abandon the North Anna line and shift fifteen miles southeast to a point near Atlee's Station, on the Virginia Central Railroad. This would place him southwest of Grant's apparent concentration toward Hanovertown and position the Army of Northern Virginia to block the likely avenues of Union advance toward Richmond.

Long overlooked by historians, Grant's masterful move had turned Lee out of his North Anna line in much the same manner that Grant had maneuvered the Confederates from their strongholds in the Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House. Lee's response, however, was equally cunning, as it enabled the Confederates to confront the Union army head-on along a new line of their selection, once again blocking the approaches to Richmond. The chess match between Grant and Lee would resume on new ground and soon add new names—Totopotomoy Creek, Bethesda Church, and Cold Harbor—to the battle flags of both armies.