Petersburg: The Wearing down of Lee's Army

Chris Calkins

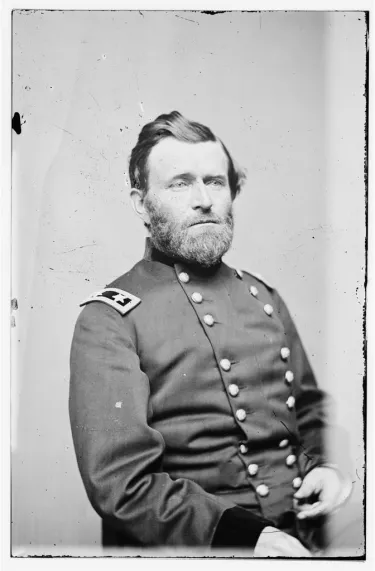

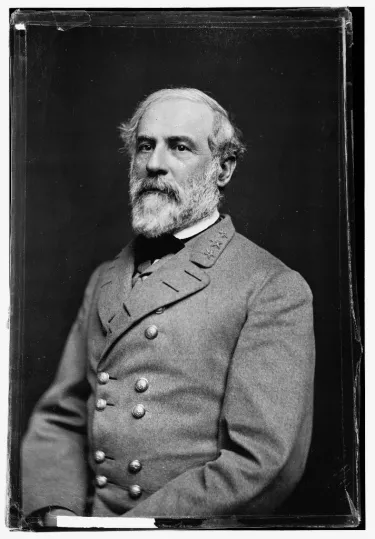

It is the spring of 1864, and the armies are still in Virginia. The Union Army is once again under a new commander. The newly appointed commander-in-chief is Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant. Although he is coordinating the strategy of all Union forces throughout the South, Grant chooses to move with General George Gordon Meade's Army of the Potomac. Meade continues to face a formidable Southern force known as the Army of Northern Virginia, being commanded by General Robert E. Lee.

Until now, the main target of the Union Army has been Richmond, the capital of the Confederacy. Grant, however, realizes that this horrendous war will not end until Lee's Army is destroyed. The determined general informs Meade that: "Wherever Lee goes, there you will go also..." The plan to overtake Richmond has now taken a back seat to the Union's desire to obliterate Lee's fighting power.

A great risk is being taken, and an even greater price being paid for this plan. Massive casualties occur on both sides as the Union troops begin their trek near Fredericksburg at the Wilderness, then move on to Spotsylvania Court House, North Anna, and finally Cold Harbor just to the northeast of Richmond. General Grant's popularity wanes as citizens in the North read about the devastating effects this movement is having on the troops. Some, though, realize that the war could now be over if not for the past retreats of less determined Union commanders.

The Northern troops approach Cold Harbor with greater manpower than the Confederates have at this site, but Grant learns a lesson he will never forget. Federal forces rush across an open field only to find that the Southern soldiers are safely entrenched. One man behind a breastwork can hold back three attackers. By June 12, there are 13,000 Union soldiers, dead, wounded, captured, or missing compared to only 5,000 Confederate casualties. By underestimating the effectiveness of entrenchments, Grant signs the death warrant for thousands of Northern soldiers, and this would be a regret that would last a lifetime. The lesson is learned, however, and Grant now focuses his mention on destroying the rail lines from Richmond's main supply base — Petersburg.

General Lee's men fought courageously throughout the Overland Campaign matching the Union soldiers step by step. However, a campaign is on the horizon that even Lee knows cannot possibly be won by the Southerners. "We must destroy this Army of Grant's before he gets to the James River. If he gets there it will become a siege and then it will be a mere question of time," Lee writes to another general. Lee is totally unaware that at this very moment, his fear is becoming a reality. Grant's army races toward the James and Petersburg to wage an attack on the city.

Why Petersburg? Petersburg is a highly industrialized city of 18,000 people. Supplies arrive here from all over the South via one of the five railroads or the various plank roads. Northern forces have cut off many of the other supply lines leading into Richmond. Petersburg is the last outpost and without it, Richmond, and possibly the entire Confederacy, is lost.

In anticipation that Petersburg will prove of major importance in Grant's plan to cut off Richmond from its supply lines, Union General Benjamin Butler's Army of the James makes two demonstrations against the city. On May 9, 1864, Federal troops move upon Petersburg from the north in an attempt to cut the Richmond & Petersburg Railroad. Confederate defenders stop them at nearby Swift Creek. A month later, Butler sends another force of combined infantry and cavalry to move into Petersburg from the south and east. This time only a small force of Southern regulars and local citizens is available to stop the threat. This band of "Old Men and Young Boys" successfully holds off the Union cavalry until reinforcements under Confederate General P.G.T. Beaureguard arrive on the scene.

The Confederates have long realized the importance of Petersburg. In fact, in 1862, a ten-mile trench line named after its engineer, Charles Dimmock, was dug around Petersburg in a "U" shape. The line anchored on the south bank of the Appomattox both to the east of Petersburg and to the west. Along the trench line were placed 55 gun batteries, whose walls reached up to 40 feet high.

At 7 p.m. on the evening of June 15, 1864 20,000 Union soldiers wage a surprise and deadly attack along the eastern portion of the defense line. A frantic General Beauregard sends urgent messages to General Lee explaining that they are under attack by a large portion of Grant's army.

Northern forces try for three days to break through the Confederate trench line, capturing parts of it each day. Lee finally realizes that Grant's target is to cut the railroads. Thanks to his swift work in acquiring reinforcements for the defenses, General Beauregard succeeds in keeping the Union soldiers at bay, although he is forced to give ground and move his trenches back upon the city.

Following many attempts and again realizing how futile it is to attack well manned earthworks, Grant decides to lay siege to the city of Petersburg. With greater manpower and a seemingly endless supply of food and materials, the Union forces decide to starve the Confederates into submission. The situation now is as Lee predicted, "a mere question of time." The main questions are not "Will the Union prevail?" but "How long will it take to break the Confederacy:" and "How many more men will have to die?"

Supplies are everything. Without proper food and clothing, not only does the body begin to die, but so does the spirit. This is a major issue for the Southerners but not so pressing for the Federals. City Point [present day Hopewell] becomes the supply base for more than 90,000 Union troops. Eight wharves are constructed which stretch a half-mile along the James River waterfront, On any given day, between 150 and 225 vessels are moored in the area where the James and Appomattox Rivers meet. Various supplies are shipped in daily. The site's bakery produces 100,000 rations of bread daily, which are then transported by wagon or rail to the soldiers on the battlefield, Those same trains and wagons return to City Point carrying the wounded and sick who are then placed in one of seven hospitals.

The supply operation is often overshadowed by the elite of the Northern command. General Grant makes his headquarters at City Point. From the east lawn of the Appomattox Manor he commands all Federal armies throughout the South. This village, virtually unheard-of prior to the war, now serves as the largest logistical operation of the entire conflict.

President Abraham Lincoln visits this site twice during the siege, once in June 1864 and once in late March of 1865. He spends two of the last three weeks of his life at City Point when it is apparent that the war is finally coming to an end. During a meeting aboard the steamer River Queen, he reveals to Generals Grant and William T. Sherman, and Admiral David D. Porter what his terms of surrender will be. The lenient terms will be the cornerstone of post-war reconciliation.

As soon as the trenches are dug in preparation for a siege on Petersburg, the Federals head out for a series of eight offensive movements to the south and then toward the west of the city. The Weldon Railroad is the first objective of Grant's movements. Although they fail to capture the rail line, the Northerners do manage to take control of Jerusalem Plank Road on June 21 - 23 and begin extending their lines to the west.

At the same time, a group of 5,500 Union Cavalry under Generals James H. Wilson and August Kautz are sent on a western raid with orders to destroy portions of the Weldon, South Side, and Richmond & Danville Railroads. They have some success at tearing up sections of the railroads but the real test is trying to return to the main Union lines. As they begin their return, over 300 slaves see their opportunity to flee toward freedom; all they have to do is keep up with the Union cavalrymen. Confederates block the way. Terrible fighting occurs with heavy casualties for the Northern troops. They have to move and they have to move fast. This means lightening their load by abandoning cannon, supply wagons, their own wounded, and the 300 devastated slaves who would later be returned to their angry owners. On July 1, Wilson and Kautz return to the safety of the Union lines with only 4,000 of the 5,500 soldiers who began the trek.

The uncertainty of how long the siege will last causes great frustration for the already homesick men. Trench life proves lonely and monotonous. A regiment of Pennsylvania soldiers proposes a possible solution to the stalemate. Their plan is approved and they dig a 500-foot tunnel underneath the Confederate line where they place four tons of black powder. When the powder is ignited a tremendous explosion occurs, killing dozens of South Carolina soldiers on the earth above. Union troops attack, assuming they will be able to rush through the cleared section of line and go straight into the city. Some of the most ferocious, merciless fighting of the war happens at this site on the morning of July 30. Federal leadership once again falls apart and when all is said and done, the Battle of the Crater yields 4,000 Northern soldiers dead, wounded, or captured while only 1,800 Southern soldiers became casualties. Grant refers to this event as a "stupendous failure."

August sees more battles as the Federals succeed in gaining control of the Weldon Railroad that approaches the city from the south. For three days (August 18 —19 and 21) Union forces under General G.K. Warren battle with General A.P. Hill's men for its fate. With the Federals victorious at Weldon Railroad, Grant's men move even further south along its length, destroying the line as they go. A few days later, at Reams Station five miles below Warrens foothold, Hill's men again pounce upon the Union troops. The Confederates force the Federals from the battlefield, which halts any further destruction of the line for a time. Lee can now bring his supplies from North Carolina only as far as Stony Creek Station (16 miles south of Petersburg) where he is forced to unload them onto wagons. From there they move cross-country toward Dinwiddie Court House and then via the Boydton Plank Road into Confederate lines.

From September 14 to 17 a daring operation takes place behind Union lines that comes to be known as Confederate General Wade Hampton's Beefsteak Raid. Riding to Coggin's Point where the Federals have a corral containing 3,000 head of cattle, Hampton's men boldly capture them and ride successfully back into Lee's lines. The beef is a brief respite from the Southerners' inadequate rations.

During the fall, Grant orders his troops to focus their attention on the Boydton Plank Road and the South Side Railroad. The Battles of Peebles' Farm (September 29 - October 2) and Boydton Plank Road (October 27) are both efforts by the Northern soldiers to cut the two remaining supply lines. The Union soldiers do not complete either objective, but they do lengthen their lines which means Lee also has to lengthen his lines to guard his critical supply routes.

Usually the arrival of inclement weather will bring a halt to military operations but such is not the case around Petersburg. In the first week of December, Union troops lead a raid upon the Weldon Railroad to destroy portions of it below Stony Creek in the direction of Hicksford [now Emporia]. While snow and sleet hamper this effort, Lee is now further inconvenienced in transporting his supplies from this region.

Keeping a constant pressure upon Southern forces, Grant once again orders his troops out of the lines and toward the plank road in February of 1865. He reaches Hatcher's Run near Armstrong's Mill on February 5 and the armies battle for three days in winter weather. Ultimately, the Union line is extended all the way to this watercourse.

March begins with Lincoln's second inauguration and the Confederate Army's morale is low. Inadequate supplies, knowledge of family hardship back home, and a horrible foreboding of impending defeat are consuming the Southern soldiers. Grant realizes this is an opportunity to position his troops to move in for the final blow. He gathers 50,000 infantry, cavalry, and artillery and readies them to break away from the siege lines and seize Lee's remaining supply routes west of the city.

As Grant prepares, Lee acts. The Confederate general has been plotting to relieve the pressure to the west by waging a surprise attack on the eastern portion of the line at Union Fort Stedman. Before sunrise on March 25 a large contingent of Lee's men begin their assault with a rush toward the Union fort. Their hopes are ambitious; their chances for success slim. Their sense of duty, however, compels them to make the desperate charge against the odds. A Union counterattack brings an end to Lee's only major offensive of the siege and the Southern general realizes his army has been diminished by 4,000 men — few of whom he can hope to replace. Grant once again has the initiative.

March 29, 1865 begins what is officially termed "The Appomattox Campaign," although its first five days coincide with the closing of the "Richmond/Petersburg Campaign." The Confederacy's days are numbered and they know it. The Union forces defeat the Southerners at Lewis Farm, which means the end of Confederate supplies from Boydton Plank Road. The South Side Railroad now means everything to Lee's forces. So, of course, this last supply line becomes the Union's main target but there are still obstacles in their way. The Battles of White Oak Road and Dinwiddie Court House are both preludes to the climactic April 1 Battle of Five Forks; the "Waterloo of the Confederacy."

A surprise afternoon attack on the astonished Confederates, coupled with poor communication among the Southern command at Five Forks allows the Union an easy victory. The Union lines are now only three miles from the South Side Railroad. Grant capitalizes on the weakened Southerners by ordering an all-out assault at various points along the Confederate line for the following morning. The Union Ninth and Sixth Corps lead off this action with the Sixth breaking the Confederate lines southwest of the city near Boydton Plank Road [now the location of Pamplin Historical Park]. The scrambling Southerners do everything they can to fight off the Union surge but they are simply overpowered. They have no choice but to escape and even that requires some heroic fighting. In one instance on April 2, the 300 Confederate soldiers manning Fort Gregg manage to hold off 5,000 Union troops to allow for the westward escape of Southern soldiers inside Petersburg. Of the 300 troops 256 sacrifice themselves so a greater number can hold on to the delusion that the Confederacy will somehow survive. On this same day, Union forces storm Sutherland's Tavern to finally wrestle the South Side Railroad from the Confederates. All supply lines leading into Petersburg are cut and the Confederates begin their retreat across the Appomattox and soon abandon Richmond.

Seven days later the fighting in Virginia ends at the sleepy village of Appomattox Court House.

Few who live in Petersburg today realize the importance and size of the conflict, which took place in their own back yard. For almost ten months 60,000 Confederate soldiers and 115,000 Union soldiers who, prior to the war, were used to having a roof over their heads, now made their homes in muddy, disease-ridden trenches where they endured extreme conditions. The presence of almost 15,000 U.S. Colored Troops provided a reminder to all as to one of the major reasons why this war was being fought. A high price was paid on both sides as the casualty number for the Southerners was estimated around 28,000 while the Union lost 42,000 in casualties. This long, deadly campaign earned the distinction of being known as the "downfall of Lee's army."