Pickett's Charge

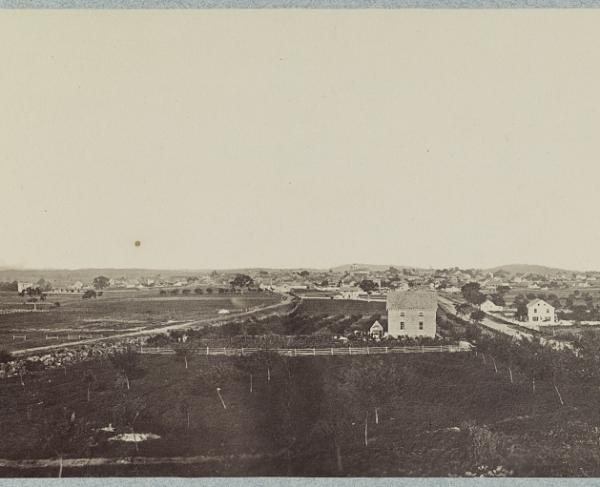

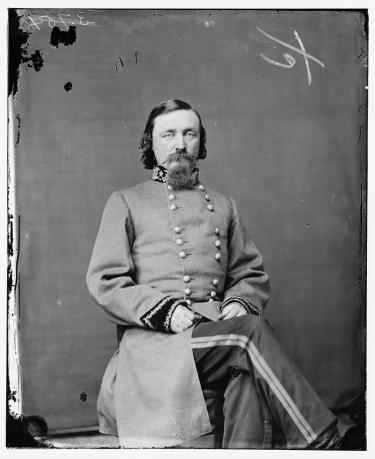

On July 3, 1863, the Union and Confederate Armies were locked in a death struggle near the crossroads town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. What began as a skirmish between cavalry and infantry quickly morphed into one of the largest battles in American history. Although the Federal forces were driven from their positions north and west of the town on the afternoon of July 1, they quickly assumed defensive positions atop and along the dominating hills and ridges to the south of Gettysburg. The titanic struggle roared back to life on the afternoon of July 2nd, with neither side gaining a decisive advantage over the other. Confederate General Robert E. Lee renewed his offensive at Culp's Hill on the morning of July 3, but to no avail. Having been assaulted on both his right and left flanks, Federal commander General George G. Meade predicted that Lee would next assault the center of the Union lines positioned along the low but defensible Cemetery Ridge. Conversely, Lee believed that the Union center was now weakened due to the assaults on the Federal left and right, and thus, the center was vulnerable to an assault. Lee believed that an all-out assault on the Federal center was the best option to win the battle. Although the assault is best known today as Pickett's Charge, named for Virginia General George E. Pickett, in reality. Pickett's all Virginia divisions made up one-third of Lee's strike force on July 3. Pickett’s three brigades of roughly 5,400 men were not in Gettysburg for the previous two days of fighting. This made them perfect candidates to spearhead a frontal assault.

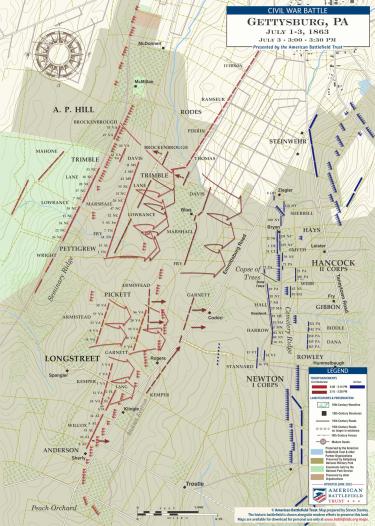

The Confederate assault plan called for a pre-assault bombardment to soften up the Union positions. Some 150 Confederate cannon were rolled into battery and opened a bombardment near 1 p.m. on July 3rd. With high humidity and with temperatures peaking at 87 degrees, cannoneers from both sides dueled for nearly two hours. With Confederate artillery ammunition supplies running low, the Rebel infantry strode from the cover of a woodline and formed for their role in the assault. Under the overall command of General James Longstreet, Pickett's division along with the divisions of Generals Isaac Trimble and James Johnston Pettigrew lurched forward near 3 p.m. Approximately 12,500 Confederate soldiers, from Virginia, North Carolina, Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee marched from their positions along Seminary Ridge across the rolling and undulating one mile of open ground with Cemetery Ridge and the Federal center as their destination. Pickett exclaimed to his all-Virginian division, “Don’t forget today that you are from Old Virginia!”

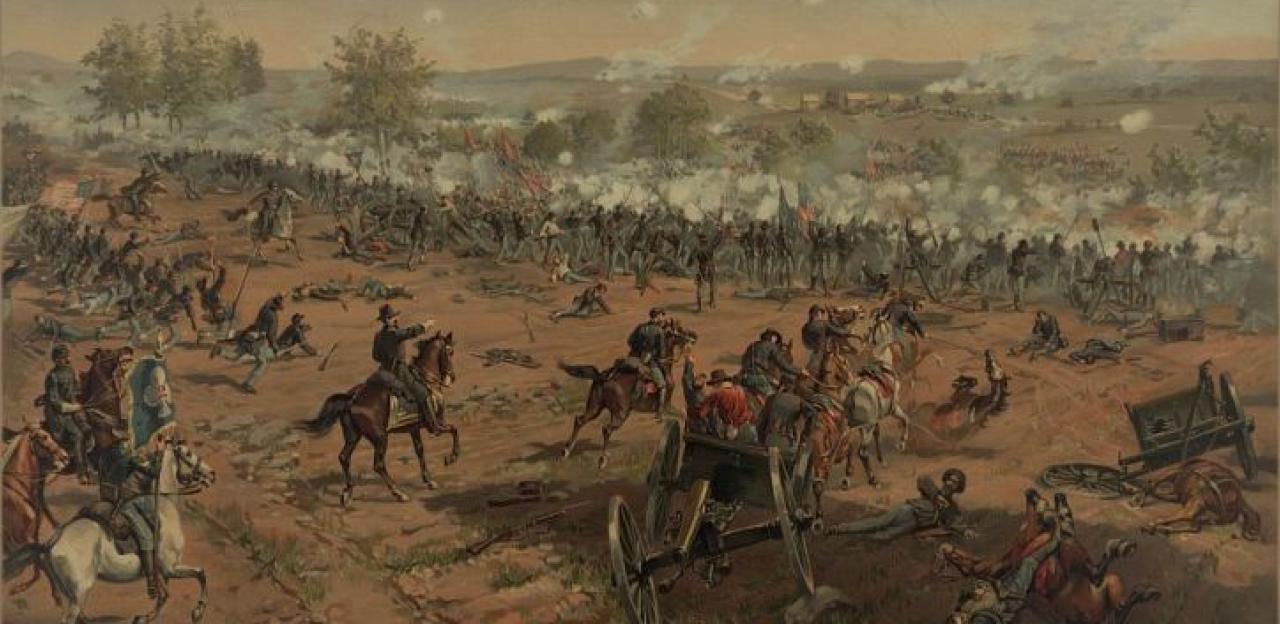

As the Confederates marched towards Cemetery Ridge, Federal artillery fire ripped open gaps in the Rebel ranks. With approximately 12,500 men marching side-by-side, artillery continuously harassed the Confederates marching across the open field towards Cemetery Ridge. As they advanced, the Confederates were delayed by obstacles in the field, such as hilly terrain and fences. The Union, in comparison, began shouting “Give them Fredericksburg!” in reference to the major Union defeat just seven months prior at the Battle of Fredericksburg, hoping to exact revenge for the crippling defeat. Union General Winfield S. Hancock commanding the Union center was severely wounded in the fray but refused to leave the field to oversee the battle’s conclusion. Hancock ordered the soldiers to rain Minie balls and cannon shot onto the field to repel the encroaching Confederate forces. One soldier from the 8th Ohio Infantry, Lt. Col. Franklin Sawyer explained the scene from the Union’s perspective during Pickett’s Charge, “They were at once enveloped in a dense cloud of smoke and dust…Arms, heads, blankets, guns and knapsacks were thrown and tossed in to the clear air…A moan went up from the field, distinctly to be heard amid the storm of battle…”

As the Confederate forces drew closer, what appeared to be a break in the Union’s line presented itself. Named the "Angle," for where the low stonewall manned by Union soldiers along Cemetery Ridge jutted back to the east, General Lewis Armistead ordered his men to take this break in the line and hold it at all costs. On the battlefield, Armistead shouted, “Come forward, Virginians! Come on, boys, we must give them the cold steel! Who will follow me?” As they stormed over the wall, the Confederate forces commandeered two abandoned cannons, but they did not have any ammunition. Federal General Alexander Webb defended the Angle and repelled Armistead's men in hand-to-hand combat. As more Union soldiers poured into the area, Armistead was mortally wounded, and what fewConfederates that crossed the wall with Armistead (perhaps 250 men) were killed, wounded, or captured. Any Confederate soldier that was not already wounded or captured fled the area for their lives. In the post-war years, one historian dubbed the Confederate breakthrough at Cemetery Ridge and is the High-Water Mark of the Confederacy.

Pickett’s Charge was a monumental disaster for the Confederacy, but a monumental victory for the Union. The Confederates lost about half of their men that engaged in the charge. Under Longstreet’s command, Pickett’s division alone suffered 2,655 casualties, Pettigrew’s division suffered 2,700 casualties, and Trimble’s brigades amassed 885 casualties. In total, there were 6,555 Confederate casualties in less than an hour of fighting. Confederate casualties during the charge accounted for approximately thirteen percent of all casualties on both sides during the Battle of Gettysburg, and twenty-three percent of all Confederate casualties during the battle. General George Meade refused to counterattack, having witnessed what his artillery had done to the Confederates, he would not allow a role reversal by attacking across the same killing fields. The Union themselves were battered and worn down from the assault, amassing 1,500 killed and wounded from the charge and many more from the previous two days of fighting.

After the fighting, Lee expressed deep regret for ordering the charge. He told a general, “this has all been my fault.” Some saw Pickett weeping over the loss of half of his division. Pickett’s after-battle report was reportedly extremely bitter, and General Lee forced Pickett to destroy it. Cavalry Captain John Singleton Mosby explained that after the war, Pickett still blamed Lee for the devastating losses and held bitter resentment for the old general. However, Pickett was asked years following the war what caused the assault to fail. He responded rhetorically, “I’ve always thought the Yankees had something to do with it.”

Pickett’s Charge was ultimately a futile all-out assault on an extremely fortified Union position. Many historians consider Pickett’s Charge to symbolize the turning tide of the war for the Union Army, although Lee's army fought on for nearly two more years. The Rebel defeat in Pennsylvania, coupled with the Federal victories at Vicksburg, Port Hudson, and in the Tullahoma Campaign—all in a six day span—marked a true turning point in the war. In Confederate memory, however, Pickett’s Charge became one of the most iconic events within the Lost Cause narrative. Nevertheless, Pickett’s Charge signaled the end of a three-day battle and the shifting tide of war in favor of the Union Army.

Further Reading:

- Pickett's Charge at Gettysburg: A Guide to the Most Famous Attack in American History. By: James A. Hessler and Wayne Motts.

- Pickett's Charge: In History and Memory. By: Dr. Carol Reardon.

-

Pickett's Charge: A Micro-History of the Final Attack at Gettysburg, July 3, 1863. By: George Stewart

Related Battles

23,049

28,063