Princeton Battlefield Monument in Princeton, NJ depicting George Washington and his troops.

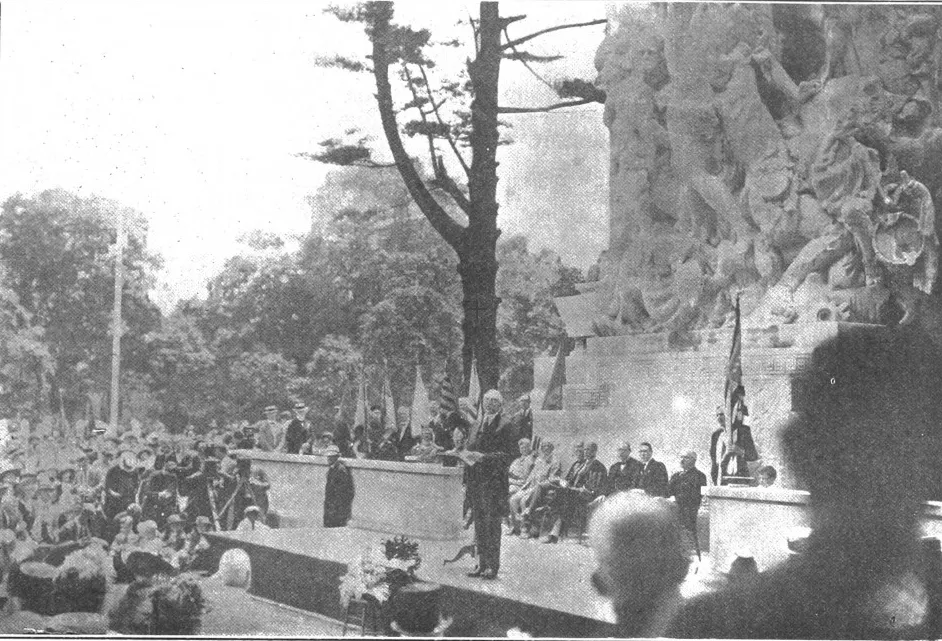

On a cloudy and overcast Friday, June 9, 1922, in Princeton, New Jersey, President Warren G. Harding stood beneath a massive limestone sculpture that he was there to dedicate. Before him a large throng of men sporting fedoras and women in hats reflecting the various styles of the age stood waiting for the President to speak. The sculpture was draped in a large American flag typical of such dedication ceremonies. The date of the dedication had been set to accommodate the President’s schedule. Only ten days earlier on May 31, Memorial Day, Harding had spoken at the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC. After speaking at Princeton he was to be given an honorary degree by the University later in the afternoon.

Joining the President on the rostrum was a field of distinguished guests including New Jersey Senators Walter Evans Edge and Joseph Sherman Frelinghuysen, Speaker of the House of Representatives Frederick Huntington Gillette, three New Jersey Members of the United States House of Representatives, New Jersey Governor Edward Irving Edwards and a slate of local New Jersey politicians and officials, including Princeton Mayor, Charles Brown.

The contingent arrived in Princeton by automobile shortly after noon, escorted by a variety of military units reflecting, in part, units of the Continental Army that had fought at the decisive battle of Princeton on January 3, 1777, including the 5th Maryland serving as honor guard to the monument and the Philadelphia City Cavalry Group, the President’s honor guard for the day. The Fifth Maryland and the Philadelphia Cavalry Group were the only remaining active military units that had a direct lineage to the combat of that fateful day.

Before going to the monument the party made its way to Morven the historic property that was once the home of Richard Stockton, one of New Jersey’s signers of the Declaration of Independence. Living in Morven was Bayard Stockton a direct descendent of New Jersey’s noted signatory. Stockton was also the Chair of the Princeton Battle Monument Association. After a brief visit by the President, Stockton joined the procession which headed straight to the monument.

Joining the official party at the monument were the sculptor Frederick MacMonnies, members of the Princeton Battle Monument Association, the President of Princeton University, and an array of delegates representing a variety of heritage and martial associations including the Society of the Cincinnati, Daughters and Sons of the American Revolution, the Society of Colonial Dames, and the American Legion among others and nine-year-old Richard Stockton III, grandson of Bayard Stockton. To this lad would fall the task of unveiling the MacMonnies creation.

As the procession with President Harding arrived the crowd rose and the band struck up the “Star Spangled Banner.” Opening the proceedings was an invocation delivered by Right Reverend Paul Matthews, Bishop of the Diocese of New Jersey, who invoked George Washington’s Prayer for the Nation. At the conclusion of Washington’s Prayer the assembled recited The Lord’s Prayer. At the conclusion of The Lord’s Prayer, Richard Stockton III lifted one of the folds of the draped American flag and the flag was hoisted from the limestone edifice to reveal MacMonnies handiwork.

Once the monument was unveiled MacMonnies briefly addressed the crowd complimenting the Princeton Monument Commission, his architectural collaborator, Thomas Hastings, and the Piccarelli Brothers of Bronx, New York, the nation’s foremost stone carving firm of the age. To the Piccarelli’s had also fallen the task of carving Daniel Chester French’s seated figure of Abraham Lincoln in the Lincoln Memorial.

After MacMonnies’ remarks President of the Princeton Battle Monuments Commission, Bayard Stockton accepted the monument from MacMonnies in the name of the Commission. Duly impressed with the massive sculpture Stockton said:

Mr. MacMonnies: -- On behalf of the Princeton Battle Monument Commission, I accept with gratitude and admiration this wonderful and artistic creation in which you have depicted one of the greatest events in American History. So important was the battle of Princeton as a factor in establishing our independence, that its memorial calls for the exercise of the highest genius. You have with patient effort finished in everlasting stone so fine a tribute to American valor and patriotism that men will from it interpret the high motive and stern resolve that charecterized the men of 1776.

Your genius is frozen in an indestructible form so that those who come after us will read, with American history, the story of your artistic conception, its wonderful charm, its brilliant beauty and its marvelous result.

You have produced the finest Battle Monument in America, if not the world, and your fame as an artist will live, as expressed in this stone, through the ages to come.

With his remarks concluded, Stockton turned the monument over to the State of New Jersey. Governor Edwards accepted the monument and pledged that the state would both maintain the monument and preserve the memory for which it stood.

Following Governor Edwards’s acceptance, Dr. Henry van Dyke, member of Princeton’s Class of 1873 and former American ambassador to the Netherlands stood and read his poem “The Ballad of Princeton battle” written specifically for the dedication.

Finally it was time for the President to speak. As he rose, with his remarks in his hand, the audience stood and gave him a round of applause. As they settled back into their seats Harding said:

My Fellow Americans:

We have come here to say the formal words of dedication and consecration before a monument in stone. But we stand to say those words, in the presence of another monument, which is the true memorial to the events we celebrate. The real monument to the achievement of Washington’s patriot army in the Trenton-Princeton campaign, is not to be sought in the work of hands or in memorials of stone. It rears itself in the institutions of liberty and representative government, now big in the vision of all mankind.

In the presence of such a monument, we can do no better than to consecrate ourselves to the cause in which at this place the soul of genius and the spirit of sacrifice shone forth with steadfast radiance. On no other battle-ground, in presence of no other memorial of heroism, could we find more assuring illumination for our hopes, our anticipations, our confidence. Here the genius of General Washington reached the height of its brilliancy in action. Here his followers wrote their highest testimony of valor. Here liberty-seeking devotion struggled through privation and unbelievable exertion, to gain the heights. The crimsoned prints of numbed and bleeding feet marked the route a pathway to eternal glory. Thither they trudged through storm and torrent; but from here, in the hour of victory, went out winged messengers to let all men know that liberty was safe in the keeping of her sons.

The President then continued to wax further on the particulars of the Trenton-Princeton campaign and the struggle of the Continental Army during the war, touching throughout his remarks on themes of valor, heroism, and patriotism. In particular he recalled a remark from a letter written by one of Washington’s greatest adversaries who had become an admirer, General Charles Lord Cornwallis who wrote, “When history shall have made up its verdict, the fairest laurels will be gathered for your excellency, not from the shores of the Chesapeake, but from the banks of the Delaware.” Harding also invoked the memory of Prussian King Frederick the Great, “who ranked the Trenton-Princeton campaign as the most brilliant of which he had knowledge.”

Continuing, Harding said, “When we view the course of human affairs from the detached standpoint of history’s student, we are amazed to discover how seldom a particular military operation has determined the results of a campaign or the outcome of a great war. Wars are writ very big in history; very much bigger sometimes than they deserve to be. Battles have seldom decided the fates of peoples. The real story of human progress is written elsewhere than on the world’s battlefields, and war and conflict have provided its punctuation than its theme. But among the expectations, among the cases in which a particular conflict has had consequences and reverberations far greater in potency than could possibly be imagined from a consideration of the numbers engaged or the immediate results, none stands out more distinctly than does the Trenton-Princeton campaign. We cannot say that the cause of independence and union would have been lost without it; but we must find ourselves at a loss if we attempt to picture the successful conclusion of the revolution, had there been another and different issue from the struggle of those hard, midwinter days.

The climax of that desperate adventure,” Harding continued, “came on the field at Princeton. Trenton had been an almost complete surprise, and easy victory. Princeton was a desperately contested engagement whose immediate result included not only an enheartening of the patriot cause, but a profound discouragement to those on the other side of the Atlantic, who were responsible for the continuation of the war. So you have erected here at Princeton a fitting memorial to the heroes and heroism of that day. We bring and lay at its foot the laurel wreaths which gratitude and patriotic sentiment will always dedicate to those who have borne the heat and burden of the conflict. Let us believe that their example in all of the future may be, as thus far it has been, a glorious inspiration to our country.”

At the conclusion of Harding’s speech the audience stood and delivered a rousing ovation of approval that lasted for several minutes. To close out the dedication ceremony the crowd was led in the singing of “MY Country, Tis of Thee.”

The conception of the monument dated to 1887 when a committee was established to not only study the idea further but also:

Resolved, that we will proceed to provide and erect a suitable ‘Monument’ in honor of the ‘Battle of Princeton’ and in memory of General Hugh Mercer and that we will ask our fellow citizens and the Legislature of New Jersey for such assistance as will entitle us to demand and receive, under the act of Congress ‘concerning battlefield monuments,’ the further sum of $20,000.

Local residents eventually chipped in $135,000, which well exceeded the total cost committed by the state and national government of $60,000.

For twenty years the project languished mostly due to the extended fund raising efforts, issues with the design, the struggle to locate a prominent site for the monument, and World War I as MacMonnies studio was located in Paris and the Congressional purse strings of the War Department, the federal department under whose auspices the Monument fell, had to manage the financial aspects of an overseas war. Eventually town fathers and the Battle Monument Association of Princeton settled on a parcel of land at the western terminus of Nassau Street in Princeton. The site was chosen in part to permit an alee of tress to line the road as visitors approach the monument. The sculpture is located a mile and a half from the field of action.

By 1907 enough funds had been raised for the consideration of selecting a sculptor. The first sculptor of choice, the eminent Augustus Saint-Gaudens, died in the same year, but the task fell to that of one of his most gifted students and assistants, Frederick William MacMonnies. MacMonnies, like his mentor had been trained at the famed Ecole de Beaux-Arts in Paris and thus his monument would be heavily influenced by French works of public sculpture and a painting by Frenchman Eugene Delacroix, Liberty Leading the People (1830). MacMonnies was chosen not only for his artistic lineage, but also because he had found success in 1890 with a moving public monument in New York City to Nathan Hale, the American school teacher turned spy who had been executed by the British. Additionally he had worked on the Brooklyn Memorial Arch commemorating the Army and Navy of Union forces during the Civil War. With a contract in hand MacMonnies entered into the work in his Paris studio with great gusto. In early 1908 he wrote the Allan Marquand, an important member of the Monument Committee, a graduate of Princeton, Class of 1874, and one of the first members of Princeton’s faculty to teach a course in Art History, “I am gratified that you have chosen me for the work and am enthusiastic about undertaking it.” In the final version of the sculpture MacMonnies would include Marquand’s portrait on one of the figures of Washington’s soldiers. MacMonnies choice of the architect with whom to work was New York based, Thomas Hastings, also an alumnus of the Ecole des Beaux Arts.

The eventual success in a monument depends on the crucial client-patron relationship, in which flexibility on both sides in tantamount to a finely finished product. MacMonnies offered several iterations of his conception to address the Monument Committee’s ideas. In correspondence between Marquand and the sculptor Marquand assured the artist that he would have the latitude needed to work from his genius, but requested that the work be “reposeful rather than dramatic” and suggested that a figure of Nike be included in the design as well as a nod to the events of January 1777 and also offered a suggestion that the work be an equestrian statue of Washington. The signed contract was the standard contract of the age, three years from signing to delivery, but rarely in such public art projects are these terms met, and the Princeton Battle Monument proved no exception as the final work took fourteen years to complete.

MacMonnies tried with little success to develop a satisfactory design using Nike. He migrated towards a colossal, thirty-five to forty foot figure of what he called “a young, fragile, and beautiful Republic … a sort of American Jeanne d ’Arc.” That too proved unsatisfactory. As proposal after proposal was refuted by the Monument Association strains developed between them and the sculptor.

In February 1912, MacMonnies suggested the following, “a monumental pylon with a heroic bas-relief, or rather haut-relief, upon it [with] figures about twelve feet in height forming a group of Washington and his soldiers in connection with a great allegorical figure of the “Republic” or “Liberty.” Writing again to the Committee in April MacMonnies further explained his conception including a drawing, “It consists of,” he wrote “a stone or granite pylon with a great bas-relief on the face and an inscription on the back. The bas-relief represents that moment in the war just before the Battle of Princeton when the armies were much discouraged, but sustained by the unquenchable patriotism of Washington. The principle figures are as follows: Washington on horseback dominating all, calm in the midst of discouragement; the men despairing, their leaders fallen or disorganized; Victory represented allegorically, raising the falling flag to triumph at the Battle of Princeton.” In November 1912 the Princeton Battle Monument Association accepted MacMonnies design.

Delays for the project continued as community wrangling over the site continued unabated. The sculptor, the Monument Association, prominent local citizens and other artists and architects weighed in until the final location was approved. Other argued that the planned fifty foot edifice was too large for such a small town as Princeton. The site was finally determined in May 1917. For another twenty months MacMonnies fiddled with the approved design delaying the process further. Fortuitously a local contractor was selected to provide the required stone, which finally began arriving in March 1919. Unlike other colossal stone sculptures the Princeton Battle Monument was carved on site. The Italian stone carvers, using a device called a pointing machine, took exact measurement from MacMonnies plaster casts made by MacMonnies earlier in the year. MacMonnies too labored on the work at the site. After spending a day working on his piece in late November 1921, the sculptor wrote “at the end of the week I felt like a different person, working out in the open air. I worked until the snow finally drove us off the scaffold.” Returning to his monument in April 1922 MacMonnies was present every day until the dedication.

As the dedication neared, Sarah Lowrie a columnist for Philadelphia’s Evening Public Ledger wrote, “I drove by the great Battle Monument and saw the sculptor quite literally putting on the finishing touches with his mallet and chisel.” Gushing, she continued, “the slender, beautiful figure of MacMonnies in his blue overalls, high up on the face of his great relief,” skillfully and with care using his tools to remove excess stone and enhance lines “into the very soul of his splendid picture.”

The World War raging on the sculptor’s doorstep also helped shape his design. Writing to his wife in 1915 MacMonnies said, “I’m having a grand time with my war relief – too grand. So glad I didn’t begin it five years ago when I should have done so. Now everything seems living and real, and heroism and sacrifice seem natural and unpretentious.” The visage of war he saw every day in Paris forced him to alter his perception, of his subject. Initially he viewed the past through a different lens, but the wars immediacy gave him additional focus and animatedly he wrote, “groping for it in the past, and suddenly the present was full of war. I had to admit that my attempt to imagine it was pale indeed compared to its reality.”

As to a suitable title, MacMonnies by 1919 was leaning towards, “General Washington Refusing Defeat at the Battle of Princeton, January 3rd, 1777.” In 1918 MacMonnies wrote a friend, “It is essential in making a permanent work of art in sculpture that every line, every form in it should not only express to the utmost capacity the spirit or sentiment of the movement , but at the same time should be woven into a pattern which also effects the eye – as chords, or arrangements of chords, affect the ear and hold the attention long enough to express the central idea – in this case, of disaster, defeat, misery, suffering despair – triumphed over and forgotten and cast aside by the unconquerable spirit of love of liberty.”

In sheer delight Marquand reported in the Princeton Battle Monument dedication book,” General Washington advancing on a wearied steed over ice-clad ground where his small, stalwart band had been pushed back and almost annihilated. Behind him is his miniature army, whose standards only are seen. He has an expression in which hope, determination and confident foresight have overcome all hesitation… In the foreground of the relief we see to the right a drummer boy shivering with cold, to the left, General Mercer falling [wounded], supported by a stalwart man of middle age, beyond whom and older man braces himself for the final resistance to the foe. In the center is a fallen hero scantily clad, and near him a falling hero from whose dying grasp has been snatched the tattered stars and stripes by a beautiful figure of Liberty, who typifies the guiding inspiration of this battle which changed the fortunes of war.” Clearly MacMonnies drew the inspiration of Liberty from Eugene Delacroix’s famous Liberty Leading the People and one might argue that with regard to the three generations represented in the sculpture he found inspiration in Archibald Willard’s heroic painting, The Spirit of 1776 (1876). MacMonnies wife, Alice Jones MacMonnies weighed in on her husband’s work, “the central theme of the group… is not an anecdotal narration of the facts of history. It is the presentiment of character in supreme crisis, as revealed visually by significant movement, gesture, and expression, which the observant eye of the artist has seen and understood and truthfully recorded in harmonious arrangement of line and mass. It shows the faith, the unfailing vision of Washington, pointing the way… to turn the tide at Princeton at the most fateful moment of the Revolution. It is the epic of the lost cause; of defeat turned into victory by the miracle of supreme heroism, sacrifice, vision, and faith, which triumphs over despair. It is dedicated to all lost causes heroically supported; to Thermopylae, Gallipoli, Princeton, and the Marne.”

On the rear of the Monument is the inscription succinctly detailing the history on the obverse side:

Here memory lingers

To recall

The guiding mind

Whose daring plan

Outflanked the foe

And turned dismay to hop

When Washington

With swift resolve

Marched through the night

To fight at dawn

And venture all

In one victorious battle

For our freedom.

For Bayard Stockton and others the wait had been well worth it. In his remarks at the dedication Stockton praised the sculptor saying that MacMonnies “produced the finest battle monument in America, if not the world.”

Critics too weighed in, one writing, “If the combination of an intimate, impressionistic handling with so gigantic a scale cannot be called wholly successful, the monument remains an example of vigorous inventiveness and fine craftsmanship. It may be out of scale with a small town and a small fight, but nothing is done half-heartedly at Princeton.”

Resources for this article were drawn from The Princeton Battle Monument: The History of the Monument, a Record of the Ceremonies Attending Its Unveiling and an Account of the Battle of Princeton which can be found at https://archive.org/details/princetonbattlem00prin and “Frederick MacMonnies and the Princeton battle Monument” by Robert Judson Clark, RECORD of the Art Museum Princeton University, Volume 43, Number 2, 1984 which can be found at https://www.jstor.org/stable/i291496.

Related Battles

75

270