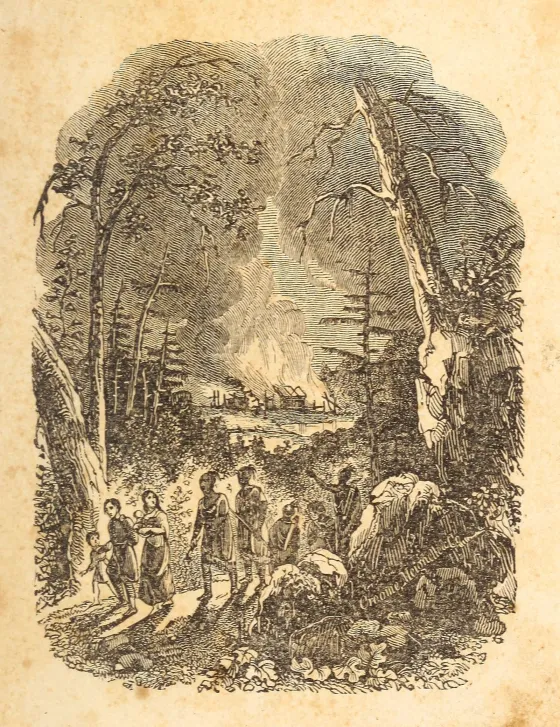

- Illustration from the cover of book entitled “Indian Wars of the United States, From the Discovery to the Present” published in 1840.

“Oui shi cat to oui!” Hokolesqua is said to have bellowed to his Shawnee warriors as they faced 1,000 Virginians on October 10, 1774. “Be strong!”

Days before, Colonel Andrew Lewis led his militiamen from the east to the confluence of the Ohio and Kanawha Rivers, where they met a combined force of between 500-700 Shawnee and Mingo led by Hokolesqua, sometimes known as Cornstalk. But the Virginians’ flank attack on Cornstalk’s forces won the day, causing the allied Indigenous force to retreat. At the Battle of Point Pleasant, Captain Lewis had secured the aim of Virginia governor John Murray, fourth earl of Dunmore, to force Cornstalk into a peace treaty. The Treaty of Camp Charlotte was signed on October 19, 1774, along the banks of Scippo Creek, today in Ohio’s Pickaway County. The treaty opened lands south of the Ohio River to European settlement. It also invited the ire of Indigenous nations like the Shawnee and Mingo against the Virginians.

Waged six months before and some 750 miles west of Lexington and Concord, some historians credit the Battle of Point Pleasant as the first battle of the Revolution, placing the spark of conflict not in New England, but in the Ohio Valley. Debate on the topic remains, but that Dunmore’s War and the actions of his militia in Ohio were an omen of things to come is indisputable.

There was certainly revolutionary sentiment among the Virginia militiamen who encamped at Fort Gower, in modern Athens County, Ohio, after their engagement at Point Pleasant. While camped there, future patriot leaders George Rogers Clark, Daniel Morgan, and others met on November 5 to discuss the developing situation, and where their loyalties should lay.

Bolstered by their victory at Point Pleasant on behalf of the king and his royal governor, but confident in their own band of frontier brotherhood, they put forward:

“Resolved, that we will bear the most faithful allegiance to His Majesty, King George the Third, whilst His Majesty delights to reign over a brave and free people; that we will, at the expense of life, and everything dear and valuable, exert ourselves in support of his crown, and the dignity of the British Empire. But as the love of liberty, and attachment to the real interests and just rights of America outweigh every other consideration, we resolve that we will exert every power within us for the defense of American liberty, and for the support of her just rights and privileges; not on any precipitate, riotous or tumultuous voice of our countrymen.”

The Virginia Gazette published the Fort Gower Resolves on December 22 — perhaps the first public declaration of the rights of American liberty over allegiance to the British Empire.

By the time the Revolutionary War waged in earnest, the Ohio territory had long-been a contested landscape. The Iroquois knew the vast river as O He Yo, the Great River, and the name soon came to encompass this land in the west. The French first explored the territory for its potential in the fur trade and were followed by English colonists who formed the Ohio Land Company to speculate for settlement there. Wealthy Virginians, including members of the Lee and Washington clans, lost potential profits when the Proclamation Line of 1763 forbid permanent settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains. George Mason’s attempts to renew the Ohio Company in 1772 met further roadblocks in 1774’s Quebec Act, in which Parliament ceded lands north of the Ohio River to the Province of Quebec, further denying colonial speculation in the west.

By year’s end, Dunmore’s War had forced the Shawnee to cede territories in the Ohio Valley to land-hungry colonists infuriated by Parliamentary roadblocks. Months later, those same colonists went to war against Great Britain and, as conflict spread along the eastern seaboard, some eyes naturally turned westward. Throughout the Revolution, the interests (and musket balls) of British soldiers, Patriots, and Indigenous nations collided in Ohio.

In December 1778, commander of the Continental Army’s Western Department General Lachlan McIntosh established Fort Laurens (located in modern-day Bolivar, Ohio) looking to engage the British at Detroit. The British took advantage of a harsh winter and deteriorating conditions there and, along with allied members of the Wyandot, Mingo, and Delaware nations, laid siege to the fort for nearly a month. The plan worked — the Patriots were in no condition to advance to Detroit and by summer, the fort was abandoned.

Further south at the Shawnee capitol along the Little Miami River, near present-day Xenia, Chief Blackfish repulsed an attack by Kentucky militia on May 29, 1779, at the Battle of Old Chillicothe. The skirmish was brought on by years of back-and-forth raids across the Ohio, perpetuated by Blackfish for increasing colonial encroachment and after Chief Cornstalk’s death at the hands of American Patriots in 1777. Though he successfully led the Shawnee to push back the Patriot militia, Blackfish died from a gunshot wound received in the battle.

The next year, General George Rogers Clark mounted a campaign to destroy the Shawnee town of Piqua, not far from Old Chillicothe in present-day Springfield. On August 8, 1780, Clark led nearly 1000 Kentucky militiamen against the Shawnee and their allies, using artillery to smash the town’s wooden stockade. Clark’s men completed a total destruction of Piqua, staying behind for days to burn the town and its fields to the ground. The largest battle of the Revolution west of the mountains had many eyewitnesses, including a 12-year-old Tecumseh whose outlook was shaped by the hostilities perpetuated by Americans there.

Nor was that the last engagement in the region, despite its backcountry location. Across this landscape and its Great River Patriot militias declared their rights to life, liberty, and property while Indigenous Americans combatted colonial encroachment and appropriation of their lands and sovereignty. In the end, Americans succeeded in settling the Ohio Territory, as veterans of America’s war for independence moved onto the once-contested landscape, claiming bounty lands for their patriotic service. But tensions remained long past the Treaty of Paris.