The Quasi-War

It is no exaggeration to say that that the United States owed its victory in the Revolutionary War to the Kingdom of France. Even before the combined victory at Yorktown, French armies and fleets engaged their British adversaries across the globe on behalf of the Americans and to draw London’s focus away from the rebelling colonies. In fact, French efforts to supply the Patriots with proper military equipment and munitions may have saved their revolution well before the drafting of the official alliance. Unfortunately for France, these extraordinary efforts drove the country deep into debt, spending at least 1.3 billion livres, undoubtedly leading to the French Revolution. As France abolished its monarchy and executed King Louis XVI, many in America wondered where that left their alliance, which surprisingly included no set endpoint in its terms of the agreement. If it remained intact, that could drag America into France’s new war with Britain, which led to a fierce debate amongst politicians on who they made their treaty with: King Louis himself, the nation he ruled, or the defunct institution he represented?

Ultimately, President George Washington decided that the 1778 Treaty of Alliance with France did remain intact with the new Republic but stressed to Congress that he had adopted a policy of strict neutrality to any conflict in Europe. This position fell in line with his belief in cementing the independence of America’s foreign policy, but it proved highly unpopular even to members of his own cabinet, who advocated closer ties with either Britain or France, depending on their party affiliation. Meanwhile, France, although politically chaotic, kept succeeding on the battlefield but looking for new means of financing their massive military expenditures. France also considered the Treaty of Alliance to be still in effect and demanded that America either honor the treaty and align with them against Britain or at least pay back some of the debt they owed France from the Revolutionary War. Washington’s position of neutrality infuriated them, especially when the United States signed the 1794 Jay Treaty with Great Britain, encouraging trade between the two countries. This added to the friction between the two nominal allies which was highlighted by key events such as the Citizen Genet and XYZ Affairs, as well as predation by French privateers on American shipping starting in 1796.

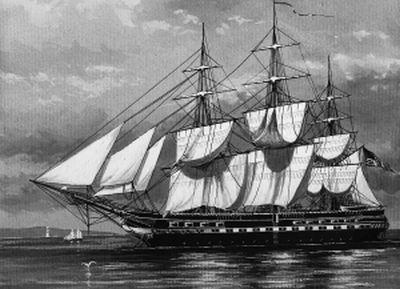

As John Adams assumed the presidency in 1797, he too remained adamant on keeping the United States neutral in European affairs, since he was key in convincing Washington to adopt the position in the first place. His firm stance caused a great deal of friction with his own Federalist Party, however, who increasingly favored war with France to stop the privateering. War was not universally popular, however, and Adams feared that acting rashly could allow Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic Republicans to sweep the next election, but he did start making real efforts to ensure the protection of America’s commercial interests. Under Washington, both the army and the navy fell under the responsibility of the War Department, but Adams thought it wise to give the Navy a degree of independence to pursue its own operations during peacetime by founding the Department of the Navy and the Marine Corps in 1798. He also convinced Congress to complete the construction of the six heavy frigates authorized four years prior, giving the Navy twenty-five warships at its disposal when Congress authorized it to target French privateers on July 7, the beginning of the Quasi-War.

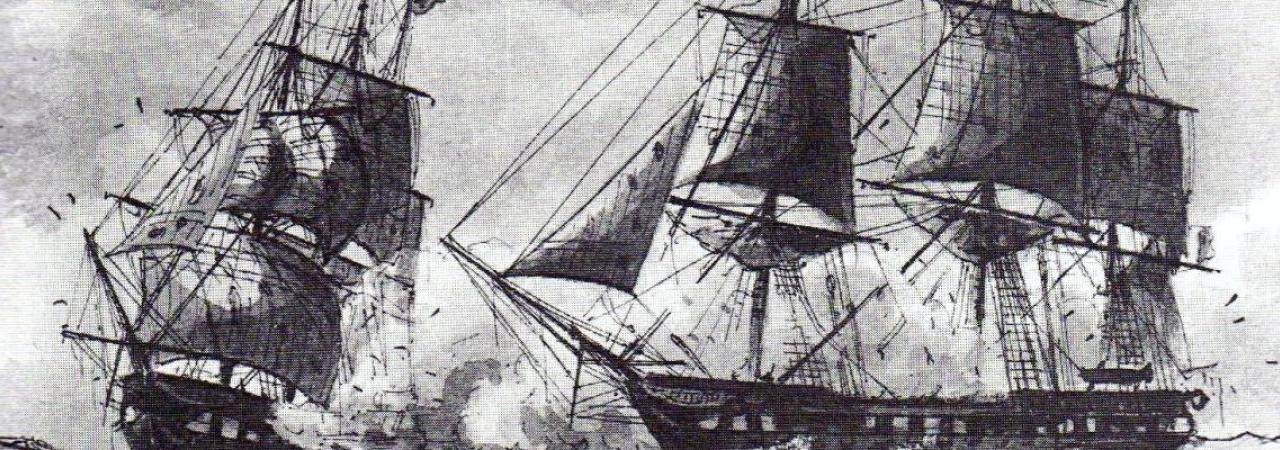

Benjamin Stoddert, the new Secretary of the Navy, understood that the nascent fleet could not hope to patrol the entire Atlantic effectively, instead feeling that it should target the waters where the majority of French privateers made base, writing to President Adams, “I feel the whole force of the importance of deciding all things in the West Indies.” His strategy also had the bonus of threatening France’s lucrative plantation colonies across the Caribbean. The undeclared war lasted for well over a year, with the majority of the action at sea, and even then, only two major engagements occurred, both of which involved the 36-gun frigate USS Constellation of Captain Thomas Truxton. A former privateer himself from the Revolutionary War, Truxton’s reputation had more to with his strict attitude towards discipline and training than his military endeavors, but the Navy possessed few seamen more experienced than him. On February 9, 1779, Truxton managed to catch the 40-gun French frigate L’Insurgente in the middle of a tropical storm off the island of Nevis. Busy fighting the weather with a cracked topmast, the French frigate became easy prey for Truxton, who literally sailed circles around her until the French captain surrendered his ruined ship. The next year, Truxton and the Constellation fought off another French frigate, La Vengeance, near Saint Kitts. Both ships took heavy damage in the fighting, and even as La Vengeance struck her colors and surrendered, the Constellation’s mainmast collapsed and forced Truxton to make repairs in Jamaica.

The Quasi-War also saw the Adams administration provide material support for the ongoing slave rebellion in the French colony of Saint-Domingue. Influenced by the ideals of liberty and brotherhood announced by the French Revolution, the slaves of the colony, the majority of the population, took up arms to secure their freedom, in what became known as the Haitian Revolution. Despite years of constant fighting and a trade embargo with the United States, the rebels managed to gain control over the colony under the leadership of a former slave, General Toussaint L’Ouverture, however, Haiti remained a colony. Knowing that Saint-Domingue was France’s wealthiest colony, Adams saw an opportunity to destroy their investment by lifting the embargo, thus empowering Toussaint to declare full independence. While the action made diplomatic and military sense, the thought of the President aiding the New World’s first successful slave revolt terrified and enraged residents of the Southern slave states.

Despite the wishes of many Federalist Party members, the Quasi-War did not escalate into a full-fledged conflict between America and France. Fears that it would, along with support for the Haitian rebels, may have contributed to Adams’ defeat in the 1800 election against Thomas Jefferson. As Jefferson and Adams campaigned, American diplomats in Europe worked to end hostilities with France and managed a breakthrough with a brand-new government. On November 9, 1799, the French Directory government was overthrown by the formidable and popular general Napoleon Bonaparte, who installed himself as First Consul of the Republic. Later called the Coup of 18 Brumaire, for the date on the French Republican Calendar on which it took place, the event largely began Bonaparte’s near-total control over the French government, but to Adams’ surprise, the new dictator was largely responsive to his overtures of peace. Adams hoped that the new navy had impressed the French, but Napoleon was mostly driven by his own agenda. As Bonaparte’s ministers negotiated a peace deal, he and his foreign minister, the ex-bishop Talleyrand, secretly plotted to restore France’s colonial empire by annexing the Louisiana Territory from their Spanish allies. Bonaparte used the negotiations with the United States to hide his actual intentions, which if known, would probably have been viewed as a direct threat to American independence. France signed the Treaty of Mortefontaine on November 9, 1800, ending both the Quasi-War and officially terminating the 1778 alliance. Napoleon signed the secret Treaty of San Ildefonso, giving France control of Louisiana once again, with Spain the next day.

From the European perspective, it can be tempting to see Bonaparte playing the Americans for fools by ending the Quasi-War, but in fact, President John Adams had accomplished much of what he set out to do: keeping the United States out of the war and establishing the centrality of the Navy in American foreign policy. Despite the limited action, many of America’s important early naval heroes also took part in the conflict, including Isaac Hull, Stephen Decatur, David Porter, and William Bainbridge. The Quasi-War, in addition to the later Barbary Wars and War of 1812, established the United States as a strong naval power to be reckoned with on the world stage.