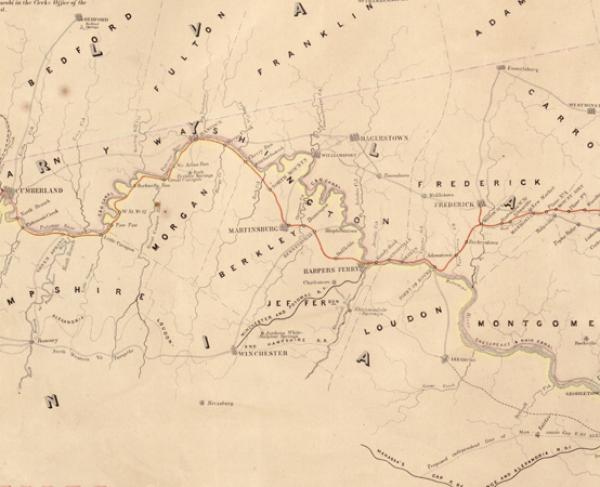

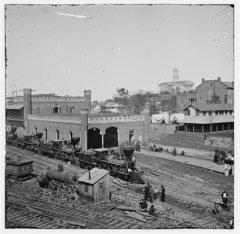

The Civil War was the first war in which railroads were a major factor. The 1850s had seen enormous growth in the railroad industry, so that by 1861, 22,000 miles of track had been laid in the Northern states and 9,500 miles in the South. The great rail centers in the South were Chattanooga, Atlanta, and most important, Richmond. Very little track had yet been laid west of the Mississippi.

Wars have always been fought to control supply centers and road junctions, but the Confederate government was slow to recognize the importance of the railroads in the conflict. By September 1863, the Southern railroads were in bad shape. They had begun to deteriorate very soon after the outset of the war, when many of the railroad employees headed north to join the Union war efforts. Few of the 100 railroads that existed in the South prior to 1861 were more than 100 miles in length. The South had always been less enthusiastic about the railroad industry than the North; its citizens preferred an agrarian living and left the mechanical jobs to men from the Northern states. The railroads existed, they believed, solely to get cotton to the ports.

There was fierce competition between railroad owners who did not want their equipment to ever fall into the hands of their rivals. The lines of competing railroads rarely met, even if they ran through the same town. The railroads also lacked a standard gauge, so that trains of different companies ran on tracks anywhere from four feet to six feet wide. Anything that needed to be transferred from one railroad to another had to be hauled across town and loaded onto new freight cars. Maintaining the trains and rail lines became a major problem as well. Most of the Confederate government's manufacturing efforts concentrated on supplying equipment and ammunition for the military. The railroads were owned by civilians and the Confederate government opposed taking over civilian industries.

The railroads, therefore, began to run into difficulties very quickly. They did not have the parts to replace worn out equipment. The Southern railroads, before the war, had imported iron from England. Once the war began, the Union blockade of the Atlantic and Gulf ports was very effective in shutting off that supply. Locomotives and tracks began to wear out. By 1863 a quarter of the South's locomotives needed repairs and the speed of train travel in the South had dropped to only 10 miles an hour (from 25 miles an hour in 1861).

Fuel was a problem as well. Southern locomotives were fueled by wood--a great deal of it. As the Confederate government pulled skilled railroad employees out of their civilian jobs and into the military, the railroad companies became badly understaffed. Replenishing the woodyards at the depots soon became impossible. Train crews eventually took to stopping along their route to chop and load wood as it was needed.

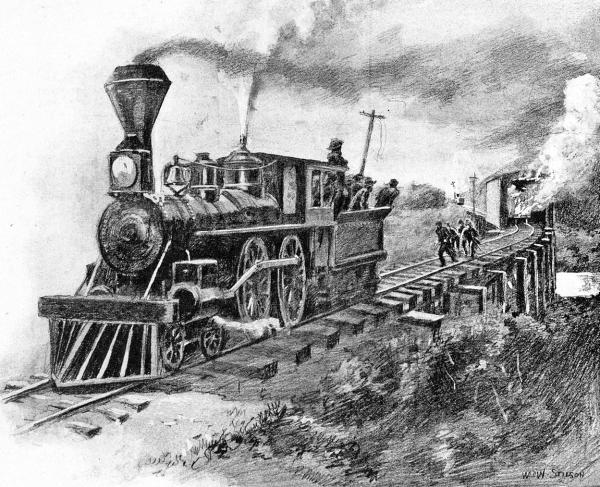

Accidents also wrecked a lot of equipment. Because telegraph communication was sporadic at best, railroad crews were often unaware of broken rails and collapsed bridges. Cattle on the tracks caused accidents, sparks from the locomotives' wood fires burned cars, and boilers exploded.

Track, too, became a problem, and crossties, spikes, and track were taken from the less important railroad lines and used on the major lines. Crossties became rotten, and rails broke (the line from Nashville to Chattanooga had 1,200 broken rails in 1862). Union troops, as they moved South, sabotaged the rails by pulling them up, heating them until they could bend, and wrapping them around tree trunks to make what were called Sherman's Neckties. The Union army also burned bridges and destroyed tunnels and captured as much railroad equipment as they could--their greatest catch was in 1863 when General Joseph E. Johnston abandoned Jackson, Mississippi, leaving 90 locomotives and hundreds of railroad cars behind.

Learn More: Railroads in the Civil War