Raymond's Battlefield Detectives Dig For Clues

In 2009, the Civil War Trust worked with the Friends of Raymond to save a 67 acre section of the Raymond Battlefield in Mississippi. Now, thanks to the efforts of a group of local historians and archeologists, the lost history of this battlefield is now being rediscovered.

BY PARKER HILLS

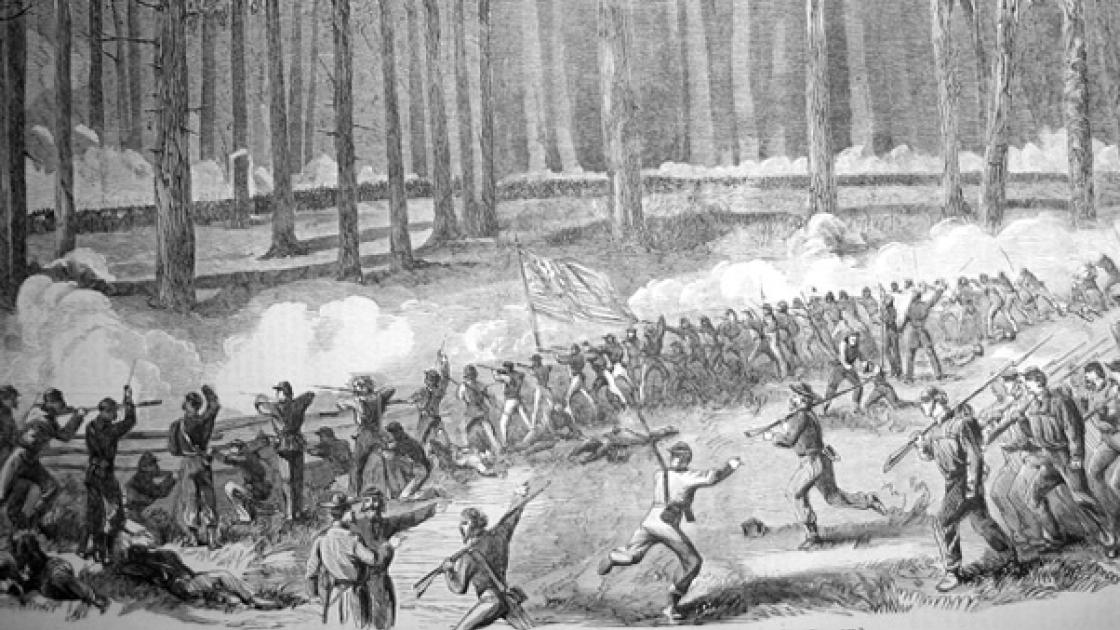

A team composed of members of Friends of Raymond (FOR) of Raymond, Mississippi, has been conducting an archaeological study of the Raymond battlefield, where one of five battles of the Vicksburg Campaign were fought in the spring of 1863. Since its formation in 1998, FOR, with the help of the Civil War Trust, has saved almost 150 acres of the Raymond battlefield. The most recent purchase was a 67-acre tract of core battlefield property which was on the market for housing lots. These are the acres which are now being studied, and these are the acres over which Maj. Gen. James McPherson’s XVII Corps fought Brig. Gen. John Gregg’s Confederate brigade in close-quarter combat for six hours. These are the acres that, for several years after the battle, blanketed almost 150 dead of both sides in makeshift battlefield graves. Although the soldiers were later disinterred for proper burial in the Vicksburg National Military Cemetery and the Raymond City Cemetery, these are the acres that remained as a silent witness to the valor and sacrifice of that twelfth day of May 1863. Clearly, they had to be saved, but who knew at the time that these acres also had a story to tell?

When the “For Sale” sign went up on the 67-acre tract in December 2006, FOR immediately went to work. Once again the Civil War Preservation Trust (CWPT as the Civil War Trust was known at the time) rolled up its sleeves and joined hands with FOR in the preservation effort. A CWPT Color Bearers tour visited Raymond in September 2007, and the preservation-minded members quickly saw the need to save the land. The price negotiations and the fund-raising began, and eventually the efforts of the two organizations came to fruition when the property was purchased almost two years later in June 2009.

The following year the Gaddis Farms of Bolton, Mississippi, always good stewards of the land, worked with FOR to clear the jungle of grass and brush off the recently-purchased property, and by the spring of 2011 the former fields of sedge grass and scrub had been transformed into rolling, verdant fields of soybeans. After the bean crop was harvested that fall, the cleared fields presented a "battlefield detectives" opportunity.

This was the moment for which an amateur FOR archaeology team, led by retired Brigadier General Parker Hills, had been waiting. Hills, a resident of Clinton, MS, and a past president of FOR, made plans to slog into the muddy fields in the December holiday season. With Hills were two trusted friends and experienced relic hunters, Jason Polk, D.D.S. of Richland, and his brother, Alan, a Raymond lawyer, who brought their metal detectors while Hills lugged his GPS, wire marking flags, storage bags, and notebook. On occasion a Jackson newspaperman, Tom Hughes, brought his detecting machine and assisted in the work.

Before the first metal detector was switched to the “ON” position, the team knew that it was working at a disadvantage, because for decades the battlefield had been scoured by relic hunters seeking valuable items. What a shame for history, because even the rarest of bullets, buckles, buttons, or weapons pulled from the ground without recording the information and the GPS coordinates are just pieces of lead, brass, or iron to be sold at a flea market or over the internet. Without recording the necessary data, the usefulness of relics for interpreting history is forever lost. As such, many of the pages of the sole copy of Raymond’s “history book in the ground” had already been forever torn out. Raymond’s archaeology team, therefore, would attempt to read what remained of Raymond’s lone history book.

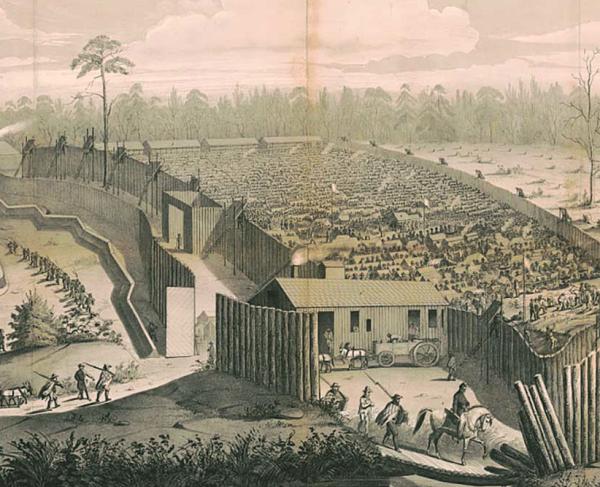

The team’s efforts were to be especially significant, because, unlike the nation's major battlefields, the acreage of the Raymond battlefield was preserved over 50 years after the death of the last of the Civil War veterans. Thus, unlike the battlefields saved in the late 19th century, none of the combatants were available to return and identify where their units had fought. Battlefield interpretation, therefore, had to rely upon Official Records reports, diary accounts, and a few sketches of the battle that were rendered by an on-the-ground newspaper artist and an Ohio soldier. All of this information, while valuable, was sketchy, so the team went to work to "interview" the ground with the hope that the archaeological evidence would help tell the story.

Despite recurrent rumors and a nagging doubt that the fields had been picked clean, on December 17 the team began its work. In almost ankle-deep mud, the workers hunted the soggy fields on Friday afternoons, holidays, and virtually every weekend in December and January. Almost immediately the efforts were rewarded. Laboriously and carefully, bullets and buckshot were coaxed from their muddy graves, and after 149 years the 67 acres, which for now have been divided into the Upper, Middle, and Lower Fields, have begun to tell their story.

The site of every bullet, buckshot, and other relic was marked with a wire flag. The flags helped the team stay on its planned search grid, and also helped to develop the “actions” in the field. When pulled from the ground, each relic was logged onto a dated sheet by GPS coordinates and description, after which it was placed in an individual, numbered, Ziploc bag. Each night the items were carefully cleaned with soap, water, and a toothbrush. Using Google Earth technology, colored pins denoting the relics were then placed by GPS coordinates on a computer map of the battlefield. The combat actions become clearer with every item dug, with the red pins indicating fired bullets, and the yellow pins indicating dropped, or unfired, bullets. Green pins were used to indicate burial detail campsites, and a lone orange pin indicated a period hatchet head that could have been used by either a soldier or a civilian chopping firewood.

After the paperwork was completed, the relics were photographed and replaced in their individual bags, which were then placed in larger, Ziploc bags with the date of the day found written on the bag. FOR will store the relics for future study and analysis, for it is not the relics themselves, but the data that they offer that is important to interpreting the battle. The relics are the first “witnesses” to appear since the combatants put ink to paper in the late 19th century.

So what has the team learned so far? Soldier diary accounts tell of a split rail fence behind which the Union line sought shelter, and that fence was vividly depicted in a drawing by on-the-scene newspaper artist Theodore Davis. However, the location of the fence line had been in question since the day the rails were knocked down. The fence was not a post and rail, such as can be seen at Gettysburg, thus, long-lost postholes could not be sought. Still, the team located the elusive fence line in the Upper Field by following the clues in the diary of a soldier from the 20th Illinois. Almost immediately after measuring the distance (described in the diary in paces and rods) that the wounded soldier said he struggled from Fourteenmile Creek to the fence, the team began to find a line of dropped .58 caliber Minié balls and smashed .69 caliber smoothbore balls and buckshot. Metal detectors and GPS device were laid down for a few moments as the team paused to envision the blue line pouring out of the woods along the southern bank of the creek, surprised by the sudden and savage attack of the 7th Texas. It was one of those “Eureka moments,” because the muddy “detectives” could almost see and hear the desperate soldiers in blue clambering their way to the meager shelter of the fence rails, harassed by buckshot as ferocious as a swarm of outraged bees. The astonished team could almost hear the reverberating sounds of .69 caliber balls and buckshot splattering against the rails, throwing splinters in all directions and causing many a Federal soldier to drop his .58 caliber Minié ball while attempting to load his rife-musket. The line of dropped and smashed balls told quite a story.

In addition to the fence line in the Upper Field, the team found a battle line just south of Fourteenmile Creek where the members believe that the infantrymen of the 20th Ohio hunkered down at the beginning of the fight. This line was vividly described by a soldier from the 20th Ohio, both in words and in a sketch. Sure enough, a straight line of dropped ammunition was found in that area, laced with unfired .58 caliber Minié balls and .36 caliber Army Colt pistol bullets, indicating that both officers and enlisted were having a tough time loading their weapons in the smoke and fire of the ferocious close-quarter combat that occurred along the creek.

In the Middle Field the team found six eagle buttons of varying size, and, in the same spot were discovered the silver “skin” remnants of a mechanical pencil. Also found was the mechanical pencil nose, which still encased three pieces of graphite lead. Near that area was found melted lead and a .58 caliber Minié ball that had been carefully and leisurely carved by a soldier into a makeshift chess piece. Also found was a layer of charcoal a foot under the surface of the ground, most probably the site of a campfire. This was undoubtedly the site of a burial detail—probably around 15 Federal soldiers—on the night of May 12, 1863, and all the next day. The buttons and pen are speculated to have come from a bloody jacket left on the field, possibly a Confederate garment due to the varied button sizes. Only fragments of the silver pencil skin with a snakeskin pattern were found, but one piece tantalizing sported the last two letters of the owner's name crudely scratched by hand into the silver. The letters are "T" and "H." Spurred on to learn the identity of this long-forgotten soldier, the team searched in vain over several days for the remainder of the pencil with the hope of determining who the owner may have been. For now, however, his identity can only be speculated.

Also in the Middle Field were found a line of dropped .58 caliber Minié balls and a number of Enfield bullets. The team is working to ascertain if this line of dropped Miniés was indeed a Union battle line or was it a line where the 3rd Tennessee charged across the creek and went to ground after receiving fire in the left flank and rear by the soldiers of the 31st Illinois? If so, then the Tennesseans may well have been using captured .58 caliber Minié balls in their Enfields, and the evidence seems to support that theory.

The team found a fired .58 caliber Minié ball 300 yards downrange from the Middle Field, but this bullet was unusual, and it deserved special consideration. The badly-bent bullet was photographed and the images were dispatched to an expert, Peter C. George, co-author of “Field Artillery Projectiles of the Civil War.” The team’s suspicions were confirmed when “Pete” George kindly and patiently advised that the Minié ball had the unmistakable "cup" marking on the nose caused by a .58 caliber Springfield Minié ball being "hard-rammed" by a .577 caliber Enfield ramrod. "Hard-rammed" means that the musket barrel was so fouled with black powder residue after continued firing that the bullet had to be shoved hard down the constricted barrel. One could almost picture a sweating and battle-begrimed Tennessee Confederate, out of ammunition after continued fighting, scavenging through the cartridge box of a downed or captured Union soldier to find some .58 caliber Minié balls, then loading and firing these balls with great difficulty into his fouled musket.

Also found was a .58 caliber Minié ball that was "reversed wormed," that is, the bullet was loaded into the weapon upside down and had to be “wormed,” or removed from the barrel with a corkscrew-like device, with the worm digging into the bullet’s base. That would be consistent with a .58 caliber Minié loaded in a .577 caliber Enfield, because the Enfield bullet was situated in the paper cartridge upside down, while a .58 caliber Minié ball was right side up. A Confederate soldier using captured .58 caliber Minié ball ammunition might, through force of habit of flipping the Enfield bullet over, turn the Minié ball upside down and load it incorrectly. Almost every relic, therefore, provided a clue to the action, but only when considered in its exact location to the other relics found in the field.

In the Lower Field the team discovered an unusual line of bullets; unusual in that the line ran perpendicular to the front battle line. The team believes this aberrant line to be where the soldiers of the 31st Illinois Infantry performed a left wheel to fire into the right flank and rear of the 3rd Tennessee. During the smoke and confusion of battle, the hapless Tennesseans had charged across the dry Fourteenmile Creek bed (which their commander, Colonel Calvin Walker, described as a “deep ravine”) through the Middle Field, and out of the bordering woods toward the Upper Field, only to be fired upon by the unseen Illini soldiers in the Lower Field to the left and rear of the Volunteers. Once again, the team paused to envision the surprise of the 31st Illinois upon the receipt of this unexpected battlefield “gift,” as well as the horror of the 3rd Tennessee upon experiencing the devastating rifle fire in its flank and rear.

It has taken 149 years for Raymond’s fields to tell their story, but the stage has now been set for much more accurate battlefield interpretation. Piece by piece, the puzzle is being assembled, and finally, the actions on the Battle of Raymond are becoming much clearer. Sometime in the future, trails and signage will tell the whole story of the Battle of Raymond that was almost lost, almost being the operative word.