Remembering Their Sacrifices: Corp. Edward J. Wisz

As a Japanese Prisoner of War, Corp. Edward J. Wisz was forced to make the Bataan Death March in April 1942. He died in the South China Sea after the Japanese transport vessel he was aboard — the Arisan Maru, was torpedoed by an American submarine and sank in October 1944.

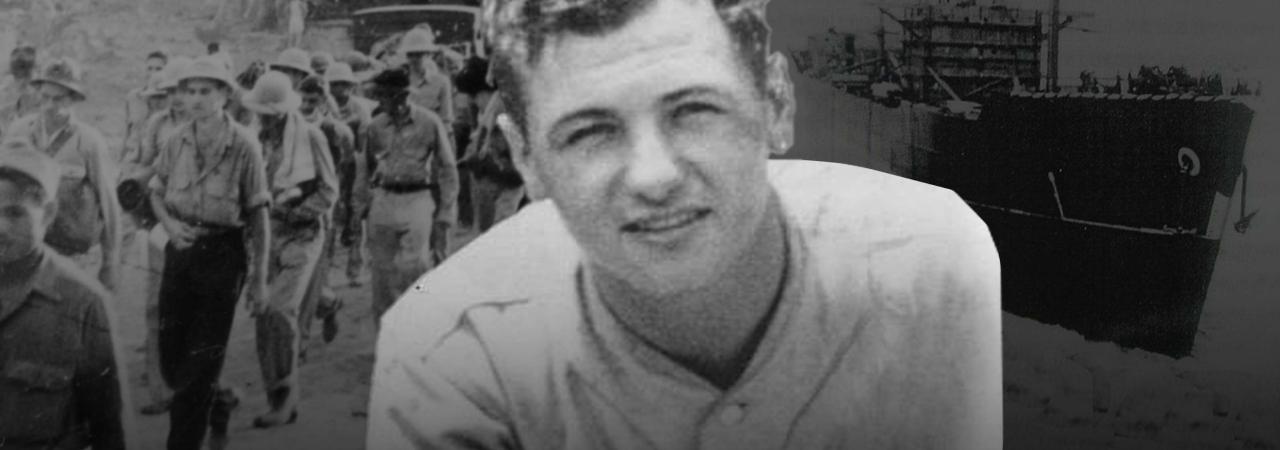

With wholehearted dedication to America’s hallowed ground and the soldiers forever bound to it, the American Battlefield Trust strives to tell the stories of the nation’s service members of years past and present. They help us to remember the hefty price of our American ideals. The following is a tribute to Corp. Edward J. Wisz, whose bravery was displayed, and fate was decided in the Pacific Theater of World War II. Hoping to keep Edward’s memory alive, the Trust’s own Senior Donations Coordinator Dawn Wisz and her husband — Edward’s nephew, Chuck, shared the soldier’s story of struggle and sacrifice.

“There were six brothers and Grandma Wisz didn't want all six going in,” said Chuck, recalling the strong-yet-weary woman. “So, my grandfather stayed back, but they were all anxious to go.” American-born to Polish immigrant parents who came to the United States in the early 1900s, the brothers’ service marked the beginning of the Wisz family’s American military legacy. Little did Grandma Wisz know the fate that her son Edward, better known as Eddie, would meet.

Eddie joined the U.S. Army’s Chemical Warfare Service on September 11, 1941 — months before the attack on Pearl Harbor. On the cusp of 25, the Pennsylvania native measured 5’8” and weighed in at 160 pounds. As the war effort took shape, he was deployed to the Pacific Theater with the 4th Chemical Company.

Dawn noted, “Every time I see his picture, I just think — he's so young.”

Eddie was on the Bataan Peninsula, in the Philippines, when the first major land battle for American forces in the war ended in disastrous defeat. He was among the approximately 76,000 Filipino and American troops who surrendered to the Japanese on April 9, 1942. A Japanese Prisoner of War (POW), he was forced to make the Bataan Death March, a brutal trek totaling some 65 miles — made even worse by the cruel treatment unleashed by their captors.

After confinement at Camp O’Donnell and Cabanatuan, Eddie was selected for transport to Japan in the fall of 1944. He was one of 1,803 POWs boarded onto the Arisan Maru on October 11, 1944. Thirteen days later, in the Bashi Channel of the South China Sea, the ship was struck by two torpedoes. After forcing the POWs back into the hold, the Japanese covered the hatch openings, and abandoned the Arisan Maru.

After the Japanese left, the POWs made it back on deck. Some raided the food lockers; others made a break for it – either by makeshift raft or the diminished strength of their own limbs. In just two hours, the ship had slipped fully beneath the waves. Only nine men survived the disaster, but Eddie was not among them. While Eddie was lost that late October day at the young age of 28, his family never let his legacy fade. "My cousin —a retired three-star general — his son, and my daughter, ran the Army Ten-Miler in his honor. And then we went to Arlington Cemetery because that's where — he's not buried there — but that's where he has a tombstone,” recalled Chuck.

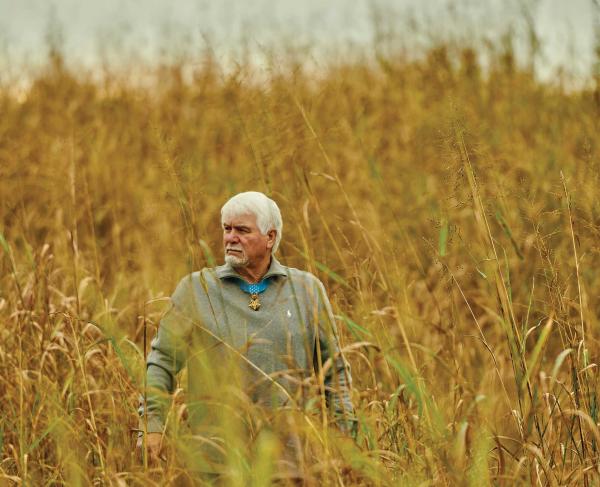

For Dawn, who was first told the tragic story while dating Chuck, the story carries intense emotions. “For [Eddie] being that young, going over there, and experiencing all that he did... he must have been a very strong person to have endured being a Prisoner of War.” And while Dawn and Chuck are unaware of any letters or personal mementos detailing Eddie’s thoughts amidst service, they know that his Purple Heart remains within the family — a tangible reminder of the wartime sacrifice Eddie made for his country.

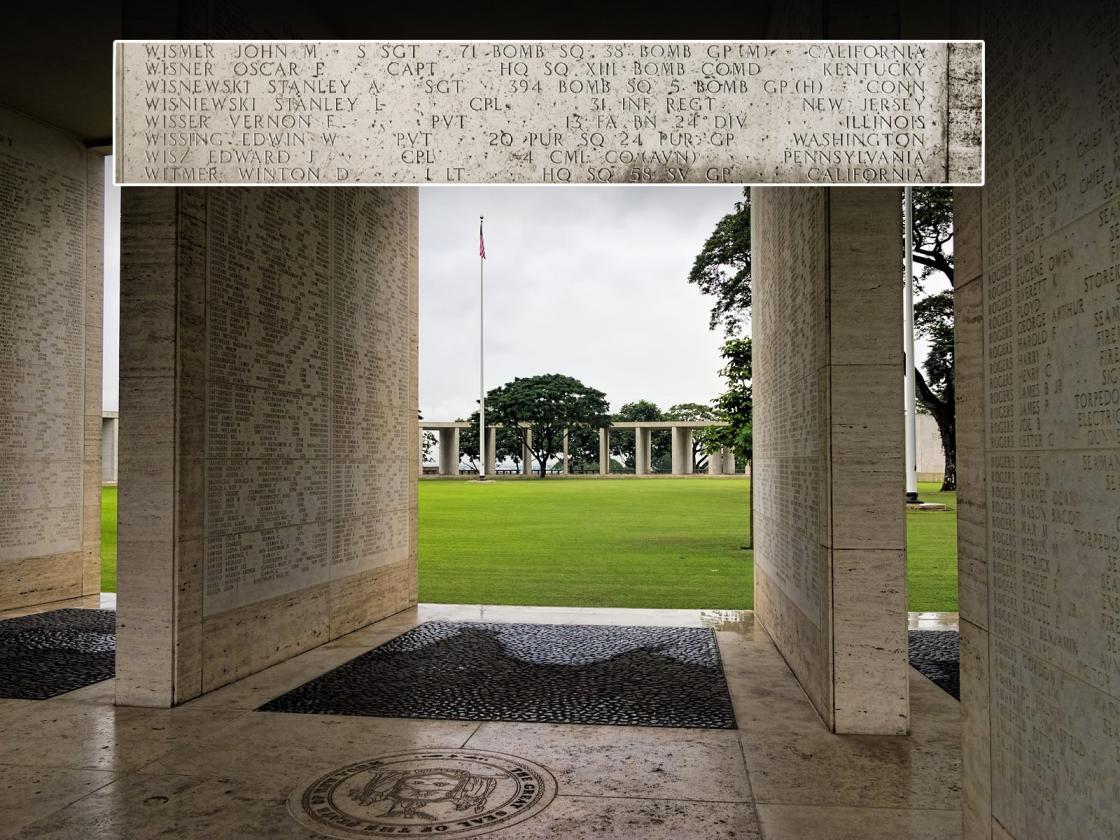

Unlike the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, which lists the individual names of the fallen, the national World War II Memorial in D.C., contains a wall of 4,048 gold stars — each representing 100 American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, and military personnel who perished or remain missing in action. His name can also be found on the Tablets of the Missing in Manila American Cemetery, the largest of all American overseas military cemeteries.

Reflecting on the role that the Trust, by way of battlefield preservation, has in remembering our nation’s fallen soldiers, Dawn remarked that “it teaches us to go out to the battlefields – to walk around and listen to what's around us. There’s this quietness there that allows us to really remember the ones who fought on those grounds. It also teaches us what sacrifices other made that make it possible for us to have the lives we do today.”