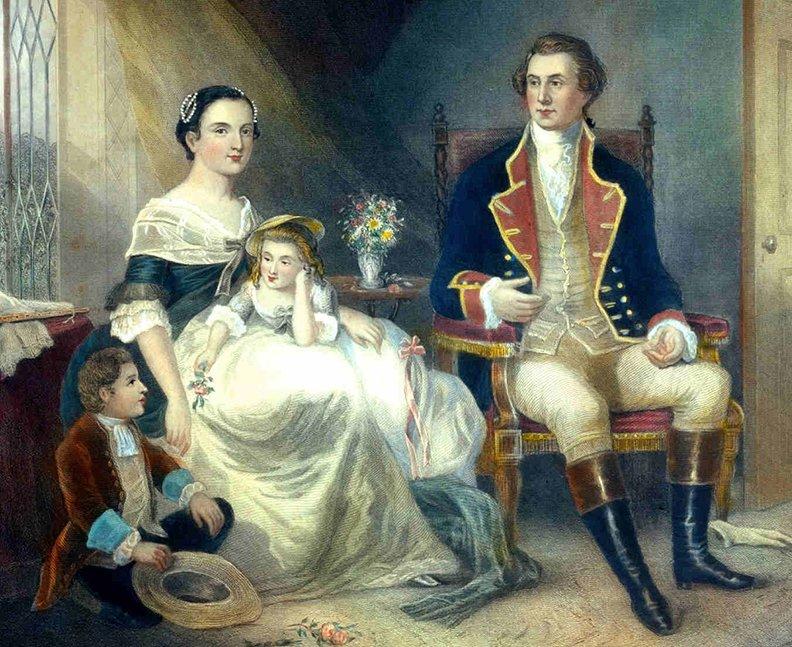

"The Artist and His Family" by James Peale - 1795

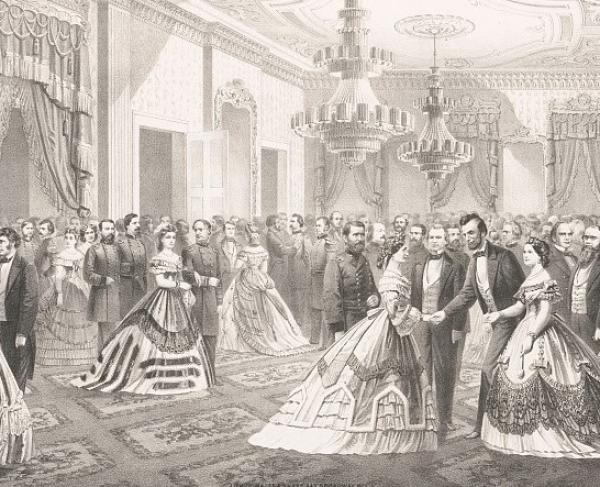

In many ways, the American Revolution saw women acting far outside their traditional gender roles. While men left their homes, farms, and businesses to support the war effort on the battlefields, many women were left alone to care not only for their families, but to take on the roles the men left behind. During the war, some women found themselves acting as full-time farmers, while others took over the business dealings of directing the work of their husbands’ trades and shops. Further, some women raised money for the support of the armies, raised their voices politically, wrote to their local newspapers, signed petitions, and took part in political protests that sometimes became violent. Some women even attempted to join the army.

In these ways, the American Revolution challenged many of the gender roles that were highly cherished as part of 18th-century Anglo-American social norms, not least of which included women exercising their voice and rights as politically-conscious citizens. While these actions were mostly seen as patriotic necessities for “daughters of liberty” as women pulled together to support hearth and home during the war, once the Revolution ended, these extra-domestic roles were not as highly regarded. Some men and women after the Revolution wanted to channel this political energy back into women’s more traditional domestic realms, for the ultimate good of the new nation. This ideology became known as Republican Motherhood. This ideological notion placed national political import on women’s roles as wives and, perhaps more importantly, as mothers.

For women, the American Revolution failed to deliver lasting, revolutionary change in terms of their status as citizens of the new republic. Women were not given suffrage or further representation in the political process, though they had acted politically during the war (it should be noted, however, that due to a language loophole, women in New Jersey did vote for a time until the language of the New Jersey constitution was corrected). The importance of women’s political agency after the war, then, was seen through the lens of their ability to indoctrinate republican ideals to their children. By teaching and reinforcing patriotic knowledge and fervor at home, republican mothers would ensure the domestic tranquility of the new nation.

Historians like Linda Kerber have pointed to John Locke’s Treatises of Government as likely inspiration for Republican Motherhood ideology. This makes sense, as the era’s Founding Fathers are known to have held Locke’s treatise in high regard and inspirational during the 18th century. Locke positioned the role of women as equal to that of men in safeguarding society through their domestic roles. Further, Kerber points to Locke and the Founding Fathers’ promotion of Republican Motherhood as akin to ancient Sparta, where a woman’s most important role was raising patriotic sons and warriors for the state. If patriotic education started early and in the home, mothers would raise families who would continue to model the ideals of the new nation. Therefore, through republican mothers, the promises of the American Revolution would self-perpetuate.

In her treatise on the rights of women, Mary Wollstonecraft argued, “if children are to be educated to understand the true principle of patriotism, their mother must be a patriot…but the education and situation of a woman at present shuts her out.” Leaders such as Benjamin Rush championed Republican Motherhood and took the ideology further to echo a call for women’s education. Rush posited that if women were to become educators at home they, in turn, needed to be educated in order to fulfill their ultimate destiny as republican mothers. His 1787 treatise Thoughts Upon Female Education was one of the first to argue for reform in women’s education. He was even instrumental in founding the Young Ladies’ Academy of Philadelphia, which taught math and geography alongside reading and writing. Rush also advocated for women to be taught the basics of civics and government—expressly for the purpose of promoting patriotic virtues to their future sons.

If Republican Motherhood advanced women’s rights in the new United States, it was through education reform. Before the Revolution, young girls received much less education than boys. After the war, women’s schools became more prevalent, especially in New England, and grew more comprehensive in their curriculums throughout the 19th century. A notable example is Mount Holyoke College, founded by Mary Lyon as the Mount Holyoke Female Seminary in 1837. The college was the first to offer women a curriculum on par with men’s college programs at the time.

It should be pointed out, however, that not everyone in the early republic supported the idea of Republican Motherhood or its accompanying education reform. Some felt that affording young women too much education would be detrimental to society. In the antithesis of its desired purpose in promoting Republican Motherhood, some early Americans argued that educated women would seek to use their knowledge to go beyond their station, and may even someday threaten to be the intellectual equals of men. Further, others argued, women may one day presume to be, in all other ways, equal to men—and may one day demand to exercise rights as citizens.

Though the original purpose of Republic Motherhood was to keep women confined to the domestic sphere raising politically-conscious sons and daughters, the movement had important legacies. As women of the early republic became more educated, they did become politically active. Many historians credit the new education afforded in the name of Republican Motherhood with the increase in women’s active roles in other social and political movements, namely the abolition movement and the rise of women’s rights campaigns of the 19th century.

Further Reading:

- Revolutionary Mothers: Women in the Struggle for America's Independence By: Carol Berkin

- "Benjamin Rush and Women's Education: A Revolutionary's Disappointment, A Nation's Achievement", John & Mary's Journal, Dickinson College By: Jodi Campbell

- Women of the Republic: Intellect and Ideology in Revolutionary America By: Linda K. Kerber

- "Rethinking Republican Motherhood: Benjamin Rush and the Young Ladies' Academy of Philadelphia", Journal of the Early American Republic By: Margaret A. Nash

- Revolutionary Backlash: Women and Politics in the Early American Republic By: Rosemarie Zagarri