Resaca: Then & Now

In 2011 the Civil War Trust met with the President of the Georgia Battlefield's Association Charlie Crawford and talked about the Battle of Resaca and the state of the battlefield today.

Civil War Trust: Can you compare and contrast the armies and commanders? Let’s start with the Union.

Charlie Crawford: Shortly after receiving his appointment as general in chief of all Federal armies in March 1864, U.S. Grant met with Major General William T. Sherman, Grant’s successor as commander of the Military Division of the Mississippi. Grant outlined his strategy for the coming spring campaigns: Federal armies would attack on every front, engaging all the Confederate armies and preventing the Confederates from concentrating against any one Federal advance. Sherman’s objective was to destroy the Confederate Army of Tennessee, at that time in its winter quarters around Dalton, Georgia.

To this end, Sherman assembled his forces in northeast Alabama, southeast Tennessee, and northwest Georgia. His largest force would be the Army of the Cumberland, 62,000 infantry and artillery and 10,000 cavalry under Major General George Thomas, Sherman’s classmate from the U.S. Military Academy class of 1840. The Army of the Cumberland contained mostly veterans from the campaigns in central Kentucky and Tennessee, but it also had two divisions that had arrived in October 1863 from the Army of the Potomac. The western soldiers chided these easterners as paper-collar soldiers.

Sherman would also have the newly reconstituted Army of the Ohio, 11,000 infantry and artillery and 2,000 cavalry under Major General John Schofield. Schofield’s army had many troops that had been in garrison duty or were newly recruited, and Schofield himself had recently arrived from Missouri.

The final component of Sherman’s force would be five divisions, about 25,000 infantry and artillery, from the Army of the Tennessee, now under Major General James McPherson but previously commanded by Sherman himself. The other armies perceived that Sherman favored the Army of the Tennessee and his protégé McPherson, who had graduated from West Point in 1853 with Schofield.

As to the commander himself, Sherman was regarded as intelligent but full of nervous energy, sleeping little and dominating conversations once he had listened to the extent he thought necessary. He had performed well though not flawlessly as a division and corps and army commander. His most valuable attribute beyond a considerable intellect and a visionary conception of war was the complete trust of U.S. Grant.

Excellent. How about on the Confederate side?

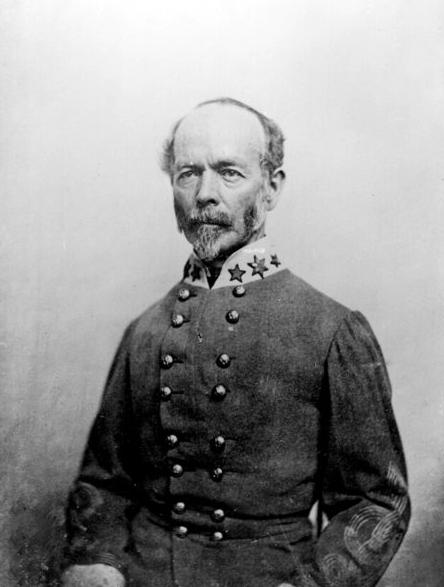

CC: Sherman’s objective was a Confederate army that had come close to collapse after a disastrous defeat at Missionary Ridge in late November 1863, but since General Joseph E. Johnston had taken command in late December, he had done much to restore the army’s condition, both physically and psychologically. Johnston graduated from West Point in 1829, along with his friend and fellow Virginian Robert E. Lee. Upon taking command of the Army of Tennessee, Johnston had initiated a furlough policy and labored to improve the supply system, bringing shoes, uniforms, equipment, and better food to the army. The men loved him for it.

Johnston had two infantry corps of over 21,000 men each: One under Lieutenant General William J. Hardee, a veteran of the western campaigns, and the other under Lieutenant General John B. Hood, a classmate of McPherson and Schofield, impaired by major wounds at Gettysburg and Chickamauga, recently promoted, and largely unfamiliar with his fellow officers in the Confederacy’s principal western army. Johnston also had 8,000 cavalry under Major General Joseph Wheeler, a 27 year old who was long on courage and daring but short on organization and discipline. Wheeler justifiably complained that he never had enough good horses for his men. The Confederate army in general never had enough horses or mules to adequately transport its artillery, supply wagons, and ambulances.

Johnston had improved his army’s morale in part by badgering the Confederate War Department for more and better supplies. He’d also sent despairing messages about being unable to assume the offensive unless he had more troops. In part because the War Department and President Davis hoped that reinforcement would spur Johnston to move against the Federals before they moved against him, reinforcements were sent to Johnston from Mobile and by the transfer of Lieutenant General Leonidas Polk’s Army of Mississippi, 20,000 men organized into three divisions that would essentially form a third corps for the Army of Tennessee. But Polk’s divisions were still in transit when the Federals began their advance.

Johnston was physically brave, having been wounded fighting Seminoles, Mexicans, and Federals, and he could elicit deep devotion from his subordinates; but he seemed incapable of decisive action and was sensitive to perceived slights. Unlike Sherman, he did not have the trust of his superiors and had a contentious relationship with President Davis. Johnston had a veteran army that had been much improved by his exertions in the first four months of 1864, but except for a brief period in the wake of the Battle of Chickamauga in September 1863, the army had a record of defeat and retreat. Ultimately, despite their appreciation of Johnston’s virtues, his men realized that he could not give them the victories that they so desperately needed.

Where does Resaca fit into the overall picture of the Atlanta Campaign?

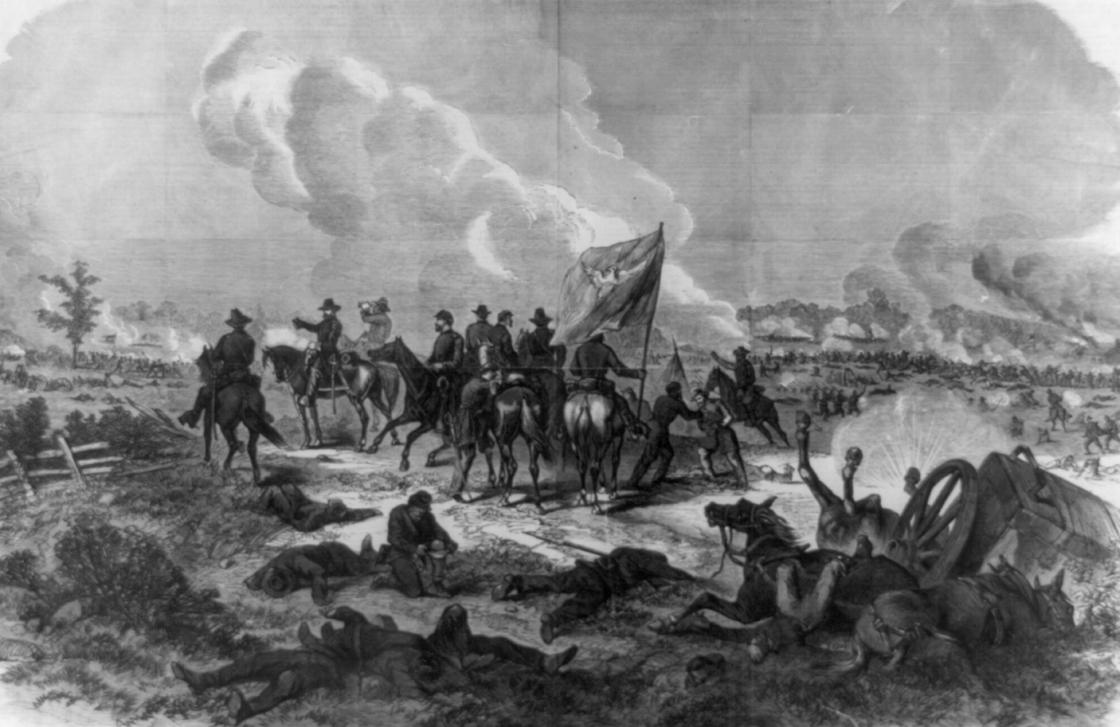

CC: When Sherman ordered the general advance that began on 7 May 1864, he sent the Army of the Cumberland towards Rocky Face Ridge and the Army of the Ohio down Crow Valley to occupy the Confederates around Dalton while the Army of the Tennessee attempted a deep envelopment through Snake Creek Gap towards Resaca. If McPherson could seize Resaca, he would be astride the Western & Atlantic Railroad 18 miles south of Dalton, breaking the Confederate supply line and forcing Johnston to retreat to the east into even more difficult terrain. As Thomas and Schofield probed the Confederate positions north and west of Dalton on 8 & 9 May, McPherson and 25,000 men passed almost unopposed through Snake Creek Gap and emerged west of Resaca. (The argument about which Confederate commander is to blame for leaving Snake Creek Gap unguarded continues to this day: Johnston? Wheeler? Both?) On the afternoon of 9 May, Sherman received McPherson’s message that the Federal advance was within two miles of Resaca. Sherman slapped a table and said “I’ve got Joe Johnston dead!” Resaca was the first tactical objective in Sherman’s campaign to trap the Confederate army, and it appeared to be within reach; but the trap never closed. Confederate reinforcements arrived in Resaca by rail just as McPherson observed the town and, combined with the garrison behind the existing earthworks, the arriving soldiers caused McPherson to waiver. Thinking Resaca’s defenders to be much more numerous than they were, McPherson launched a few probing attacks but then withdrew his divisions towards Snake Creek Gap. While McPherson hesitated, Confederate reinforcements continued to arrive by Resaca by rail. Deeply disappointed, Sherman consulted with Thomas, who advised moving most of his own Army of the Cumberland through Snake Creek Gap to press the attack against Resaca. Sherman concurred, and the bulk of the Federal forces moved towards and through the gap on 11 and 12 May.

When informed that the Federals were in position to menace his railroad supply line, Johnston sent three divisions towards Resaca late on 9 May. When his observers on Rocky Face Ridge reported much of the rest of Sherman’s force was headed for Snake Creek Gap, Johnston marched his own army to Resaca after dark on 12 May, occupying the existing earthworks before daylight on 13 May and quickly improving the fortifications. Instead of a lightning move to cut the Confederate supply line at Resaca, the Federals would now have to fight an entrenched Confederate army, which they proceeded to do from 13 through 15 May 1864.

What are some of the terrain features around Resaca, and how did they affect the campaign and the battle?

CC: The terrain around Resaca is marked by ridges, though they are much less pronounced than around Dalton. Some open land adjoins the numerous creeks and rivers. Just south of town are the vital road and railroad bridges across the Oostanaula River, which flows mostly from east to west. East of town, the Oostanaula is formed by the junction of the Coosawattee and Conasuaga Rivers. The Conasauga arrives from the north and provides protection to the east for any army that is occupying the hills west and north of Resaca. The high ground occupied by the Confederates formed a rough fish hook, with its shank resting on the Oostanaula, then proceeding north until its barb curved around to the east to touch the Conasauga. While the Confederate left rested on the Oostanaula, an opponent who crossed that river to the west and then marched eastward could approach the railroad and threaten the Confederate line of supply and retreat. But Sherman’s task was not to precipitate a series of Confederate retreats: He was to fix and destroy the Confederate army. Since the arrival of the Federals signaled that they were not attempting a flanking movement to the west, Johnston readied his army for a fight at Resaca.

The fighting on the northern part of the field was intense. Why were they fighting there?

CC: The early phases of the battle occurred west of town, where the Federals first pushed Polk’s newly-arrived soldiers off the Bald Hill on 13 May. On 14 May, the early action was heaviest in the center as the Federals attacked unsuccessfully across Camp Creek Valley. Late on 14 May, Johnston received word from Wheeler’s scouts that the Federal left (i.e., the northeast part of the Federal line) was “in the air.” Johnston ordered Hood to attempt a flanking attack northward from the barb of the fishhook; but the Federals had already become concerned about the vulnerability of their left flank, and Williams’ division of the XX Corps arrived to blunt the Confederate attack just as it was gaining momentum.

Frustrated with his inability to breach the Confederate defenses on the ridge east of Camp Creek, Sherman swung more forces to his left on the night of 14-15 May and attacked in the northern sector of the field the next day. The Federals initially made progress but were stalled by mid afternoon. Again, Johnston ordered Hood to attack the Federal left, but Hood could advance only Stewart’s division because two other divisions were already engaged. Informed that a Federal division had crossed the Oostanaula River and could soon be menacing the Confederate line of retreat, Johnston cancelled Hood’s attack, leaving Stewart’s division to suffer heavily as it attempted to withdraw. In the darkness of the early hours of 16 May, Johnston withdrew his army southward across the Oostanaula, burning the bridges when the rear guard reached the south bank. The Battle of Resaca was over.

Did artillery and earthworks play a significant part in the fighting on the land we saved in 2011?

CC: The Confederate earthworks in this northern sector had been constructed in the previous few days, unlike some of the established works closer to town and the vital bridges. The trenches in this part of the Confederate line were strong but not flawless. Captain Max van den Corput’s artillery battery had been positioned in advance of his infantry support, and the Federal assault on the afternoon of 15 May captured the guns. The Confederates couldn’t regain the guns, but the Federals couldn’t haul them off because of infantry fire. After dark, the Federals dug out the front of the revetments and rolled the guns down the slope. The remnants of the gun positions with the distinct cutaways are still visible on the property that is covered by the easement.

What was Johnston’s goal at Resaca? Was he only delaying the inevitable?

CC: Most of us have trouble viewing the Atlanta Campaign as anything but inevitable, in part because of Johnston’s pattern of retreating and not taking the initiative. To be fair to Johnston, his goal at Resaca and thereafter was to bloody the Federal armies and make the campaign too difficult for the Federals to sustain. As the Federals moved towards Atlanta, their supply line got longer, and they had to use more troops to protect it. Further, the enlistments for many of the Federal regiments expired in the summer, so if Johnston could make the prospect of victory seem distant, the Federal soldiers might not reenlist. Finally, if Lee could frustrate Grant in Virginia and Johnston could frustrate Sherman in Georgia, the northern populace might tire of the war, replace Lincoln in the November election, and seek a peace with the Confederacy on negotiated terms. Lincoln himself felt for much of the summer of 1864 that he would not be reelected. So, feeling that he did not have the men or the transportation to take the offensive, Johnston determined to conduct the best defense he could, knowing that defenders in prepared positions normally inflict more casualties than they suffer.

Resaca is a bloodier battle than many others in the Atlanta Campaign. Why is Resaca not a household name?

CC: Perhaps because of the way the campaign unfolded. In the east, the titanic clashes in the Wilderness and around Spotsylvania Court House occurred early in Grant’s Overland Campaign, which ended in a siege that wasn’t resolved until the following April. For the Atlanta Campaign, Resaca was the first major clash, but the Federal armies in the west were accustomed to advancing after a battle, even indecisive ones, unlike the dramatic scene in the Wilderness where the Army of the Potomac realized that Grant was leading them south rather than back north.

Although some battles in the Atlanta Campaign were less bloody than Resaca, others were not; and they led towards a dramatic climax at Jonesboro in early September. While Grant appeared to be stuck in the trenches at Petersburg, Sherman was able to take Atlanta, providing bold headlines for the northern newspapers and significantly improving Lincoln’s chances for reelection. Consequently, the later battles are remembered more than the first major battle of the Atlanta Campaign

Interestingly, Resaca was the only battle during the campaign when almost every unit on both sides was engaged. In subsequent battles, even the major ones such as Peachtree Creek and Atlanta and Jonesboro, only portions of the Federal and Confederate forces were engaged.

One of the Federal participants at Resaca was a young topographic engineering officer named Ambrose Bierce, who later gained fame as a writer. In 1887, he published a short story titled “Killed at Resaca,” so it’s not as if the battle went entirely unremembered.

How well preserved is the Resaca Battlefield and what have been some of the preservation challenges?

CC: The battlefield was bisected by the construction of I-75 in the 1960s, considerably damaging trenches on the south end and in the center of the field and altering the terrain along the highway corridor. Fortunately for preservation, the town of Resaca has not expanded significantly; and even though residential and commercial construction and timbering have damaged some of the earthworks, much of the field on either side of the interstate highway retains its rural character. Some of the people who developed and profited from the textile industry in this area of Georgia bought large properties where they built a house or a few houses and left the remainder largely untouched. When one of these large parcels containing much of the Camp Creek Valley west of I-75 became available in 1998, the Friends of Resaca Battlefield worked with Georgia Battlefields Association (www.georgiabattlefields.org) to urge the state of Georgia to purchase the land as the beginnings of a battlefield park. In 2000, the Georgia Department of Natural Resources bought 505 of the original 1200 acres; but plans for a park were put on hold when the 2003 recession affected state revenues. Not until October 2008 did the state have a ground breaking for a visitor center, just in time for a more severe recession to constrain state spending. The latest plan is to install parking, walking trails, and interpretive and directional signs in 2011 in preparation for the Sesquicentennial, but the major expenses of a visitor center and a permanent staff are still deferred. Currently, the state-owned land is inaccessible by vehicle unless a private land owner gives permission, and even a visitor on foot will have trouble accessing the site in anything but ideal weather.

East of I-75 and southeast of the town itself, the Friends of Resaca took on the task of saving Fort Wayne, which was originally built by the Confederates to guard the bridges over the Oostanaula River and was significantly improved by the Federals in the summer of 1864. Friends of Resaca persuaded the Gordon County government to buy 65 acres in 2003, and the Friends did a considerable amount of brush clearing in preparation for the day when the site may be interpreted and open for visitation. A master plan was completed in 2007, but funding is still lacking.

East of I-75 but northeast of town is the 483 acre property that was the location of the Confederate right and that is subject of the current Civil War Trust fund raising to buy a conservation easement. This property was about to be foreclosed when it was bought by the Trust for Public Land (TPL) in 2008. TPL’s preservation model is to buy land that faces an immediate threat and subsequently sell it to a preservation-minded buyer as quickly as possible. Since land values have fallen over the last two years, TPL has been unable to sell the property without a loss and was unsuccessful in getting an American Battlefield Protection Program (ABPP) grant. TPL consequently proposed a conservation easement to lessen the amount that a buyer would need to raise. After getting an appraisal for $1,550,000, TPL was able to get commitments of $1,350,000 from ABPP, $100,000 from Gordon County, and $100,000 from the Civil War Trust. Georgia Battlefields Association is giving $50,000 towards the Civil War Trust’s $100,000 commitment.

Wow! This is why local groups are so important to the preservation fight! How can a visitor see the battlefield today?

CC: Resaca has about a dozen state historical markers and one well-hidden monument to indicate that a battle occurred there, but a visitor trying to understand the battle without a guide will be challenged, even if following the driving tour published by Friends of Resaca Battlefield (www.resacabattlefield.org).

While the state land may soon have parking, trails, and signs that would facilitate visitation, it remains separated from Fort Wayne and the 483 acre property east of I-75. The hope of Friends of Resaca Battlefield, Georgia Battlefields Association, and other preservation organizations is that the latter two sites will soon have more interpretive markers and that all three may be connected by a walking trail, though the interstate highway and other busy roads present considerable challenges to pedestrian activity. Despite the physical and funding obstacles, a visitor to the battlefield should soon have a much better chance of gaining some understanding of the significant fighting that occurred there in mid May 1864.

Do you have a favorite story associated with the Battle of Resaca?

CC: Every battle provides a number of stories of bravery, luck, sacrifice, irony, kindness, etc. For Resaca, I’ve always been touched by the actions of the Green family after the battle. The Greens lived on land that is part of the conservation easement. After the battle, the Greens, especially Mary Green, organized the local populace, almost all women, to relocate Confederate dead from their rude graves to proper burial in a plot of land owned by the Greens. After the war, the Federal government organized a program to exhume any Federal dead and return them to their families or rebury them in national cemeteries; but Confederate dead were not included. At her own expense, Mary Green sent letters to newspapers throughout the south, indicating that if a family had lost someone at Resaca, the remains might be interred on the Green property; and the relatives were welcome to claim the body. Most families did not have the money to come get a body or have it shipped home, so Mary made sure that each set of remains was identified if possible and given a decent grave. Today, the Confederate Cemetery, which adjoins the easement property, contains over 400 graves, many of them unknown but maintained in a beautiful setting thanks to the efforts of Mary Green and her successors.

Charlie Crawford is the President of the Georgia Battlefields Association, a non-profit preservation group, and editor of Georgia Battlefields monthly newsletter. He has made over 80 presentations and conducted over 30 tours relating to Civil War sites in Georgia.

Charlie grew up near Philadelphia and has a B.S. in Applied Mathematics from Georgia Tech. He entered the Air Force, served in Vietnam, and retired as a colonel in 1995. he returned to Atlanta in 1996 and is currently director of operations for an information technology consulting company.

Charlie also has an M.S. in Systems Management from the University of Southern California (USC). In addition to being a member of Georgia Battlefields Association and the Civil War Round Table of Atlanta, Charlie is a life member of the Civil War Trust and The Military Officers Association of America.