One of the lesser known cities that took part in the Revolutionary War, Richmond, Virginia, was home to many revolutionary figures that influenced the creation of the United States. One influential figure that was from Richmond was Patrick Henry. Henry delivered his famous “Give me Liberty or Give me Death” speech at St. John’s Episcopal Church where the spirit of the Revolution was heard by delegates of the Second Virginia Congress. Henry’s speech persuaded the delegates to assist in the war effort, as well as leave a lasting impression both on the delegates present, and on patriots throughout the 13 colonies.

Richmond became the state capital in 1780, in the midst of the Revolutionary War, with the election of Thomas Jefferson as governor of Virginia. Jefferson publicly declared that the capital of Virginia would move to the small town of Richmond due to its centralized and defendable location. However, a major deciding factor in moving the capital to Richmond for Jefferson was support for the Revolution. Richmond housed fewer loyalists compared to Williamsburg. Williamsburg had been the capital of Virginia since 1699, and over time British governors of Virginia, such as Lord Dunmore, had created a long-lasting loyalist base. Jefferson took many drastic approaches to loyalists residing in Virginia by signing a proclamation banishing them the colony. Jefferson’s main priority in making Richmond the capital was to separate Virginia from its British roots. It was an attempt by Jefferson to eliminate political resistance in Virginia’s new revolutionary government.

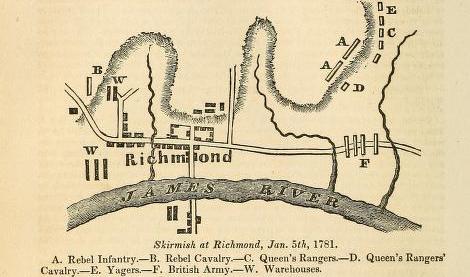

Richmond did not witness much combat at the beginning of the war. The British were primarily focused on hunting down General George Washington’s Continental Army in the New England colonies. However, beginning in 1781, Richmond and her surrounding neighbors along the Virginia Peninsula were witnesses to the conclusion of the war. On January 1st, 1781, during the second British invasion of Virginia, the recent traitor to the patriots, General Benedict Arnold, sailed along the James River towards Richmond. For three consecutive days, Arnold and his new fleet laid waste to colonial plantations and settlements along the James River. On January 4th, Arnold and his mostly loyalist soldiers arrived at Richmond, defended by a thin force of 200 militiamen. Arnold sent out a small detachment of men, and when Arnold’s forces confronted the 200 militiamen, the militiamen fired an abysmal musket volley and fled into the woods. Jefferson saw the militiamen flee, and called for a mass evacuation of military supplies, as well as government officials from the city. When Arnold marched into Richmond, he was met with no resistance. Arnold established a headquarters in Richmond and wrote to Jefferson asking for the city’s entire supply of tobacco and military supplies, and Jefferson was furious. Jefferson refused to let the man that betrayed the Revolution take Richmond’s supplies. After Arnold received Jefferson’s refusal, he ordered Richmond to be burned. Arnold’s men set fire to homes, businesses, government buildings, and robbed the city of all it owned. Jefferson got word of the destruction of Richmond and was outraged. He called upon Colonel of the Virginia militia Sampson Mathews to dispose of Arnold and his soldiers. Mathews gathered as many men as he could, approximately 200, and set out to find Arnold. Mathews found Arnold and fought him in an irregular style of war, formulated by Continental Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene. Mathews and Arnold skirmished over the following days around Richmond. Arnold began to have his forces withdraw to Portsmouth after taking near continuous losses. Mathews pursued Arnold back down the Virginia peninsula. Arnold’s men burned more plantations and towns in their retreat to Portsmouth, which served as an excellent guide for Mathews. Mathews managed to chase Arnold back down to Portsmouth, which ended the Richmond campaign on January 19th, 1781.

After the Raid on Richmond, George Washington began to focus his attention on the Southern theater of the war, and Arnold. Washington dispatched General Anthony “Mad Anthony” Wayne and one of his most trusted subordinates the Marquis de Lafayette to pursue the traitor. By the Fall of 1781, British General Sir Charles Cornwallis found himself cornered and besieged in Yorktown, Virginia. Washington, in tandem with his French allies led by Jean-Baptiste, comte de Rochambeau laid siege to British forces at Yorktown. On October 19th, 1781, General Cornwallis surrendered. The Treaty of Paris, signed nearly two years after the events at Yorktown, gave formal recognition to the former colonies as the United States of America.

Richmond’s story during the Revolution is an important one. Patrick Henry gave the colonists a prominent and immortalized voice for the Revolution. Serving as the new capital of Virginia, Richmond gave Virginia a carte blanche to distance themselves from their former British roots, establishing Virginia as a patriotic state in the newly formed Union. After the Revolution, Richmond was the home of Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall, a veteran of the Revolution. After his terms as governor of Virginia, Thomas Jefferson became the third President of the United States. Although Richmond did not witness much combat, the people that resided in Richmond both during and after the Revolutionary War were some of the most influential figures in American history.

Further Reading:

- The Invasion of Virginia, 1781 By: Michael Cecere

- Richmond During the Revolution By: Harry M. Ward and Harold E. Greer, Jr.