A Roar From The Portals of Hell

Wednesday, October 14, 1863 began pleasantly enough for the hardened veterans of the Union Second Corps, encamped north of the Rappahannock River in Fauquier County, Virginia. A young officer on Brigadier General John C. Caldwell’s staff was almost poetic in his description of the scene, writing, “the crimson tinted foliage of an early October morn framed in the open ground, completely enclosing a glorious picture of an army en bivouac…the general appearance of contentment and ease made a picture not to be forgotten.”

The glorious picture would not last long. As Caldwell’s men brewed their coffee and geared up for the day, Confederate Major General J.E.B. Stuart and his cavalry were preparing a surprise for the bluecoats. Without warning, Stuart ordered his horse artillery to fire upon the unsuspecting Yankees, replacing ease and contentment with excitement and chaos in a skirmish that would later be known as Coffee Hill.

For the next several hours, a minor battle raged near the small town of Auburn as the Union Second Corps clashed with elements of Stuart’s Cavalry and Lieutenant General Richard Ewell’s infantry. The Federals quickly recovered from their initial shock, and were able to stave off the hesitant Rebel advance long enough to make an escape. The march that was to culminate in the battle of Bristoe Station had begun.

It was only a few days earlier that the two great antagonists in the Eastern Theater of the war had been staring at one another across the Rapidan River, to all appearances getting ready to settle in to winter quarters. With the Federal Eleventh and Twelfth Corps in Tennessee helping to raise the siege of Chattanooga, the Army of the Potomac appeared content to remain there for the remainder of the year. Lieutenant Frank Haskell, an aide to Major General Gouverneur K. Warren, bemoaned the “dull inactivity” and wrote, “I see no prospect of immediate operations by this Army.”

But at the very moment Haskell penned those lines, Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia was on the move. Lee had initiated a flanking movement similar to the one he had used against Major General John Pope’s Army of Virginia more than a year earlier. The Confederate commander hoped to get behind Meade’s army and cut off its escape route across the Rappahannock River. If Lee succeeded, the Army of the Potomac would be at his mercy.

However, Union Major General George G. Meade had anticipated the maneuver. Unbeknownst to Lee, signalmen on Pony Mountain had broken the Confederate code, and were reading messages from the Southerners’ signal station on Clark’s Mountain. On October 7, Meade’s signalmen intercepted messages that clearly indicated that some sort of movement was underway. Two days later, Meade and his chief of staff, Major General Andrew A. Humphreys, saw for themselves the gray columns moving beyond the Union right flank.

For Lee’s flanking movement to succeed, his men would have to move fast. Unfortunately, he was forced to take a roundabout route to avoid detection by Union outposts. The long march gave Meade and Humphreys the time they needed to move the Army of the Potomac out of its camps and across the Rappahannock. Meade’s army was safe – or so it seemed.

Lee, however, had no intention of stopping on the banks of the Rappahannock. His men poured across the river at Warrenton Springs, arriving in the village of Warrenton on the afternoon of October 13. Their goal, he told Confederate Secretary of War James Seddon, was “with the view of throwing [the Federals] farther back toward Washington.”

It took the Union high command some time to grasp Lee’s intentions. Now that the Clark’s and Pony Mountain signal stations were closed down, Meade had to rely on his cavalry for information. His horsemen erroneously reported that Lee had halted his advance and was dug in around Culpeper. Eager to goad Lee into attacking him, Meade recrossed the Rappahannock and formed a new line along Fleetwood Heights, north of Brandy Station. When Meade realized the error, his army crossed the stream for a third time and began a hurried retreat along the Orange & Alexandria Railroad.

The rival armies were now engaged in a race for Centreville. Although the Army of the Potomac was slightly behind its adversary, Meade’s men had the benefit of the inside track. To outflank the bluecoats, the Southerners would have to take a circuitous route that would add many miles to their march. Worse, Ewell’s Second Corps and Lieutenant General A.P. Hill’s Third Corps would have to share part of the route, further slowing down the movement.

Despite the cool autumn weather, the speed of the march made it a difficult one for both armies. The historian of the 116th Pennsylvania described it as “one of the most trying campaigns ever experienced by the men.” Adding to the misery, the men in blue were carrying an eight-day supply of cooked rations in their haversacks.

During a brief rest from the rigors of his march, Ted Barclay of the Stonewall Brigade jotted down a few lines for his sister. He was worried that Meade’s army might escape. “Hill is endeavoring to get into their rear,” he noted, “but is somewhat behind time.” He warned her, “the Yankees may succeed in reaching their entrenchments around Centreville.” However, if caught, he told his sister, “I think they will get such a thrashing as will teach them a lesson for some time to come.”

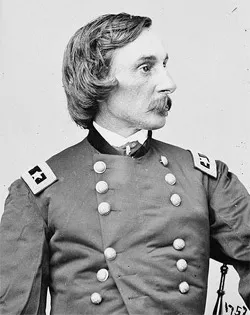

Giving the invader a thrashing was exactly what “Little Powell” had in mind. As Hill’s Corps approached Bristoe Station, he began to see evidence that the enemy was retreating in haste. Campfires were still burning, and the road was littered with blankets and haversacks. Hill sensed that he had the Yankees on the run, and he was anxious to take advantage of an opportunity to punish them.

From his perch on a hill northwest of Bristoe Station, Hill thought he saw his opportunity. In the distance, he could see elements of the Union Third and Fifth Corps crossing a local stream known as Broad Run. Realizing that his chance to strike the Federals was fleeting, he ordered his lead division under Major General Henry Heth into battle without reconnoitering the area. Heth recalled in his memoirs that Hill “urged the troops, my division, to attack speedily.”

There wasn’t enough time for Heth to deploy his entire division, so Hill had him throw the North Carolina brigades of Brigadier Generals W.W. Kirkland and John R. Cooke into line, with the brigade of Brigadier General Henry H. Walker to follow on Kirkland’s left. The gray brigades moved quickly toward the Broad Run, hoping to catch the remaining bluecoats on the western side of the stream. But instead, the Tar Heel brigades began to draw fire from skirmishers on their right flank. The hunters were about to become the hunted.

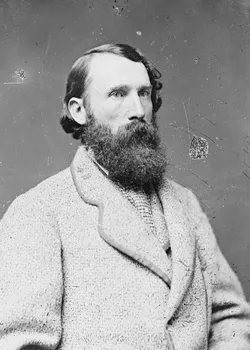

The once-bored Lieutenant Haskell now watched in fascination as the Confederate lines pivoted away from Broad Run and toward the railroad embankment. Here, the men of Warren’s Second Corps, weary after their escape from Auburn, had begun to take shelter. The railroad embankment not only protected Warren’s men, but concealed them as well.

When the two North Carolina brigades were 50 to 150 yards away from the embankment, the hidden Union troops opened fire. Haskell later wrote, “they fell thick as leaves, stricken by a rain of bullets – they broke and fled.” Union Brigadier General Alexander Hays, commander of a division in the Second Corps, described the volleys that tore into the Confederate ranks as a “perfect hurricane of shot.” In the face of this onslaught, the butternuts “wavered, rallied and charged again, but in a short time broke in dismay and sought shelter in the woods.”

From the Confederate lines, one of Kirkland’s officers witnessed the devastating fusillade. He observed that the line behind the railroad embankment opened up with “a roar from the portals of Hell.” The Tar Heels literally fell in droves. Eventually, more than 600 would be pinned down near the railroad embankment and forced to surrender. The rest fell back in disorder.

Ironically, the North Carolinians weren’t the only ones to feel the wrath of the Union guns. According to Major Henry L. Abbott of the 20th Massachusetts, his regiment suffered five casualties from friendly artillery fire. In his report, Abbott remarked, “Such fire from the rear is much more trying than a fire ten times more destructive from the enemy.”

The target of the Federal guns was not Abbott’s regiment, but six Rebel cannon atop a hill just west of the Brentsville Road. The rain of Union iron had disabled one cannon and had driven off the gun crews of the other five. The dazed survivors of Cooke’s and Kirkland’s brigades were in no shape to defend the pieces. The guns were easy prey for some enterprising Yankees.

As it turned out, nearly everyone in a blue uniform that day claimed credit for capturing the cannon. Almost every regimental commander in the vicinity stated that his men were the first to take the guns. Major Abbott claimed credit for two captures in his report, calling it “a very audacious and skillful thing.” Meanwhile, Lieutenant Colonel Walter Taylor of Lee’s staff naturally took the opposite view, describing the capture as “unpardonable” and remarking, “I have felt humiliated ever since.”

Three Confederate generals were wounded in the carnage at Bristoe. A bullet fractured Kirkland’s left arm, and he would be unable to return to command until February. Cooke’s shinbone injury would knock him out of the war for six months. Brigadier General Carnot Posey was the most seriously hurt of the three; he would succumb to his wound one month later, on November 13.

The losses weren’t limited to Confederate officers. While rallying one of his companies, Major Abbott saw his brigade commander and good friend Colonel James E. Mallon fall with a mortal wound. “He was going towards me to speak to me when he was hit… He was a magnificent officer and a great loss to the brigade.”

When the sun finally set on the battlefield, nearly 2,000 men lay dead or wounded on the ground. So many Confederates fell during the brief but bloody encounter that most were buried in trench graves. When the Union army reoccupied the battlefield on October 21, General Hayes described the landscape thus: “Long lines of pits marked the last resting places of those who were no longer our enemies, and further up the slope the ground is literally covered with the carcasses of dead horses, indicating the terrible effectiveness of our artillery fire.”

Warren was delighted with his victory. He told his brother, “We are today the heroes of the army.” Soon after the battle, Warren told Meade’s aide, Lieutenant Colonel Theodore Lyman, that “we whipped the Rebs right out. I ran my men into the railroad cut and then just swept them down with musketry.”

The Northern reaction to the Bristoe Campaign was mixed. Although few disputed Warren’s claim to victory, opinion was divided over whether Meade’s retrograde movement was a brilliant maneuver or a humiliating defeat. Union General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck tartly informed Meade that “Lee is unquestionably bullying you.” Whitelaw Reid, a muckraking reporter for the Cincinnati Gazette, described Meade as a “Dancing Master” who “took to his heels and started for Washington.” Later in the month, he would describe the campaign as a fiasco and pin the blame on President Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton for not removing the “Snapping Turtle” after Gettysburg.

Meade had his defenders, however. Corps commander Major General John Sedgwick told his sister that, “General Meade has always been ready to give the enemy battle, but with such a long time to bring up his supplies, he was always anxious for his line of retreat.” An officer in the 71st Pennsylvania was astounded by the rumors that Meade would be relieved. He wrote his brother, “We feel every confidence in Meade, and if anyone succeeds him but McClellan, the dissatisfaction will be intense.”

In the Confederate ranks, there was no such debate. Nearly everyone agreed that the Bristoe campaign was a fiasco. Artilleryman John C. Haskell remembered Bristoe as a “most unfortunate blunder” that cost the graycoats far more men and supplies than they could afford to lose. Sandie Pendleton, a former aide to the lamented Stonewall Jackson, remarked, “Hill is a fool and woeful blunderer.”

Hill received official censure as well. War Secretary Seddon wrote, “The disaster at Bristoe Station seems due to the gallant but over-hasty pressing of the enemy.” Confederate President Jefferson Davis was equally critical, stating unequivocally, “There was a want of vigilance.”

The worst censure, however, came from Lee himself. Legend has it that while riding together over the rain-soaked battlefield, Lee replied to Hill’s apologies and explanations by stating, “Well, well, General, bury these poor men, and let us say no more about it.”