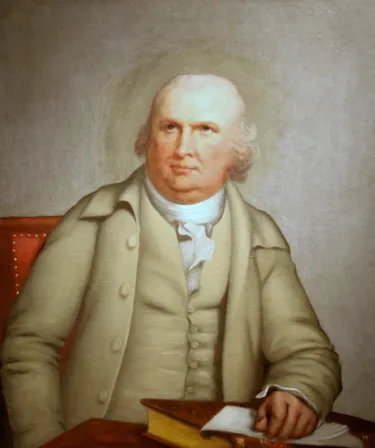

Most Americans know the names of George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and Alexander Hamilton, but among the leaders of the American Revolutionary Period that we refer to as the Founders, there remain a select few who fall under the radar. One such individual, Robert Morris, is one of these examples. He was not a military leader, but a skilled politician. He was not a future president, but a mind of finance and enterprise. He is one of only two delegates of the era to have signed the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the United States Constitution.

Morris was born in Liverpool, England in January 1734 to Robert Morris, Sr, and a woman named Elizabeth. It appears young Robert was the product of an affair. His father’s business, that of a shipping broker, kept him away, and the boy was raised by his maternal grandmother. Morris Sr. established a successful merchant business exporting tobacco from Maryland in 1747, and soon his son joined him in the New World as his apprentice. Young Robert transferred to Philadelphia where he studied under the tutelage of Charles Greenway, a member of the Library Company of Philadelphia, founded by Benjamin Franklin. In 1750, a freak accident took the life of Morris, Sr., and Robert found himself at sixteen the inheritor of about twenty-five hundred pounds sterling. He spent the next several years learning the trading industry in the care of Charles Willing, a former business partner of his fathers. It is here where Robert’s schooling in mathematics became quite useful; his knowledge of business ledgers and finance were impressive, and he soon became fast friends with Charles’s son, Thomas. Politically and socially connected with the upper echelons of Philadelphia society, the Willing’s provided the young men a platform that would – upon the death of Charles Willing and Robert completing his apprenticeship with the firm - culminate into a partnership, the Willing Morris & Company.

The Willing Morris & Company became quite successful because of several methods that saw them monopolize the industry. Willing and Morris sought to insure other cargo vessels and aggressively pursued trade with the Mediterranean and India. The combined effects opened new markets to Philadelphia and North America while simultaneously making both men very wealthy. They primarily dealt with merchant goods but also traded African slaves on occasion. In 1763, Morris fathered a daughter out-of-wedlock in Philadelphia. Known as Polly, he would provide for her the rest of his life – much like his half-brother Thomas, whom his father sired in Maryland before Robert arrived from England. In 1769, Morris married Mary White, the daughter of a wealthy lawyer. They would have seven children together.

In the years leading up to the American Revolution, Morris found himself on the side of opposing British taxes on merchant goods. He opposed the Stamp Act of 1765 and the following measures of Parliament that continued to levy a burden upon American shipping vessels. When the First Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia in 1774, Morris was not elected as a delegate but held court with many of the arriving members who sought his counsel and opinion on how to navigate petitioning for a repeal of the Intolerable Acts. However, Morris was appointed to the Committee of Safety by the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly in 1775 following the outbreak of the American Revolution in Massachusetts. Morris was given the task of providing munitions and gunpowder to the Continental Army, something he evidently did with much success. This won him a nomination to the Second Continental Congress the following year. Morris tried to bridge calls for independence by radicals with those who were in favor of neutrality and petitioning the King. Because of his reputation as a successful merchant, Morris was elected to several committees that oversaw the necessity in using maritime shipping to aid the American cause. He also oversaw the founding of the Continental Navy. As the summer of 1776 produced the formal calls for American independence, Morris, sympathetic as he was to protect the colonies from British aggression, refused to vote for independence. Along with a colleague, he abstained from the official vote, allowing the remaining Pennsylvania delegates to support independence. He would eventually sign the document in August 1776 along with the majority of Congress.

As events and the war progressed, the financial situation for the new United States became dire. The British navy had enacted a blockade along the eastern coastline that effectively made commerce and trade impossible. Because an American navy did not technically exist beyond what was planned, Congress employed privateers and merchants to sack British ships where they could. The chaos that ensued did disrupt British dominance on the Atlantic at times, but it did not revive merchant commerce. Morris was also part of a secret committee that was pursuing French support. While American diplomats Silas Deane and Benjamin Franklin had been dispatched to Paris to negotiate the support of the French Court, Morris sought out munitions and military supplies. Morris also played an active role in trying to establish American credit. Because of the structure of the colonial governments, each former colony maintained an autonomous financial structure under the guidance of the British government. To complicate matters, aside from British currency, other European currencies, along with colonial papered promissory notes, circulated to form the monetary commercial exchange on the continent. With the war in full swing, the new state governments tightened their belts and refused to loan out or pay the requested sums asked by Congress. This problem was not fixed when the Articles of Confederation, the first federal constitution of the United States, was passed in 1777. Congress could request monetary support from the individual states, but the state governments were under no legal authority to honor these requests. By 1780, the American economy was near default, and the paper money that had been printed, known as Continentals, were worthless due to inflation. Without Congress able to pay for the needs of the war, foreign diplomats had to convince friendly European governments to loan them hard coin and gold.

In 1781, with the situation remaining in peril, Morris began bankrolling the needed supplies of the Continental army on his own. He officially served as the Superintendent of Finance, the precursor to the Treasury Secretary. Using his personal credit, he put up the necessary funds to ensure the loans would be honored. The American army began receiving the supplies it needed, and for the next three years, Robert Morris personally financed the American Revolution out of his own pocket. “Morris notes” became widely circulated promissory notes within the ranks of the army. However, one individual could not finance every aspect of what the war required. Changes had to be made in the way the confederation government operated. In 1782, Morris was among a handful of nationalists within Congress who were calling for changes to the Articles of Confederation. Unable to pay the soldiers of the Continental Army because of structural precedence, Morris, along with Alexander Hamilton and Gouverneur Morris, began corresponding with a select few of the officer staff within Washington’s headquarters. Though Morris had nothing to do with the Newburgh Conspiracy, letters do indicate that the three congressmen were receptive to ideas that would force Congress to adopt new ways of enforcing jurisdiction over the states. At the same time, Morris, with Hamilton as his advisor, had been scheming of ways to create a financial sector for the government to operate. It was Morris who proposed assuming the war debt by creating credit through a national bank. However noble these plans were, the Confederation Congress refused to listen. Both Hamilton and Morris would resign from Congress in 1783-84 as the debt from the war continued to balloon with no solution to paying it off.

By 1786, it was clear among many in the country, particularly those who had always been critical of the ineffectiveness of Congress to govern over the states, that something had to change. Morris was nominated as a Pennsylvanian delegate to attend the Annapolis Convention, the precursor to the Philadelphia Convention the following year that produced the Constitution. It was Morris, in attendance at Philadelphia, who nominated Washington to preside over the deliberations, a move that was unanimously accepted in order to give the convention its legitimacy. As a nationalist and long critic of the Articles of Confederation, Morris supported the Constitution and would sign it in September 1787. Morris was then elected to the US Senate by Pennsylvania in 1788. He helped broker the Compromise of 1790 that saw Hamilton’s plan for a national bank in assuming the individual states’ war debt to establish national credit in exchange for the federal capital to be in the south. As a resident of Philadelphia and representative of Pennsylvania, he would serve in the Senate until 1795, all the while continuing his many business ventures. By the 1790s, with the opening of new territories on the continent, land scheming had become big business. His reputation remained intact, but his personal wealth began to take large hits.

Among the many homes the Morris family owned and resided in during their time in Philadelphia were a manor home known as “The Hills” along the Schuylkill River and the brick-laden house on Market Street that would serve as the president’s house during the 1790s when the city was the nation’s capital. Morrisville, Pennsylvania is named after him following a home he owned there as well as the uncompleted manor house known as “Morris’s folly.” The latter came about as Morris’s luck finally ran out in 1797. Land scheming had claimed the finances of many of the era’s leaders, and Morris came into trouble when creditors demanded payment with the financial panic of 1797. Along with several of his business partners, Morris tried to leverage what he owed by selling off shares of stock they had invested in to raise revenue on their landholdings. Instead, the stock went under. Unable to pay his debts, Morris lost everything and was placed in debtors’ prison in 1798. Morris owed nearly three million dollars to creditors, an unthinkable amount of money at the time. Despite pleas from his friends, who were unable to financially assist him, Morris remained in prison until 1801. Upon his release, several of his colleagues, and the Bankruptcy Act of 1800 recently passed by Congress (aiding his release), forgave much of his debt by allowing him to declare bankruptcy. Along with his wife, he was allowed to live quietly in Philadelphia off a small stipend until his death on May 8, 1806.

It is indeed ironic that the man who became known as the ‘Financier of the Revolution’ nearly died penniless in debtors’ prison after years of bad investments. It’s clear that Morris, ever ambitious, got in over his head with land speculating in the 1790s. He would not be the only victim of such a risky enterprise, but the reputation of others seems little affected by those endeavors. For Morris, his reputation has suffered because of the nature of his life’s work: finance. In the years that followed the ratification of the Constitution, many skeptics of the federal bank system, particularly among Jefferson and his circles, readily attacked what they saw as the establishment of an American aristocracy, modeled on London, that favored the wealthy merchant class over the agrarian class. The pivotal roles that Morris played in the critical years of the Revolution carried less weight in these foes’ eyes than the continuous scheming for more monetary gains that animated Morris’s life. Is this a fair critique of the man? Indeed, he was drive by profit for much of his life. Finance was his game. But however he may have conducted his personal affairs, his handling of affairs in the service to the United States are clearly solid in their importance to our country’s founding. Without Morris, who breathed a sure confidence in merchant and maritime capability, much of the work done by one individual would likely have been divided over several. And the outcome of such an arrangement leaves us with uncertainty to its success. It was Morris who won the confidence and trust of Washington, Franklin, Adams, Hamilton, and others. Not through his promises, but through his actions and their results. Because he wasn’t a military leader or future president and did not end his life on a literal “high-note,” historians have unfairly discarded Robert Morris as an individual unworthy of our attention. Yet his presence and continuous involvement in American politics during the founding era are irreplaceable to its outcome. Though Alexander Hamilton receives just credit for getting the nation’s financial industry up and running, it was Robert Morris who was the engine behind the founding of America’s financial sector.

Further Reading

- The Quartet: Orchestrating the Second American Revolution By: Joseph J. Ellis

- Robert Morris: Financier of the American Revolution By: Charles Rappleye

- Robert Morris’s Folly: Architectural and Financial Failures of an American Founder By: Ryan K. Smith

- Financial Founding Fathers: The Men Who Made America Rich By: Robert E. Wright & David J. Cowen